The Legacy Of Polish Posters

Before the era of globalized entertainment made movie posters look the same in every country, Polish artists were creating their own versions for the internal market. What resulted was a whole school of artists trained in the art of the poster. This article presents a short historical look at how this movement was born and how it developed, form its art–related beginnings at the end of the 19th Century to the golden era of the film posters throughout the 20th Century.

The Beginnings

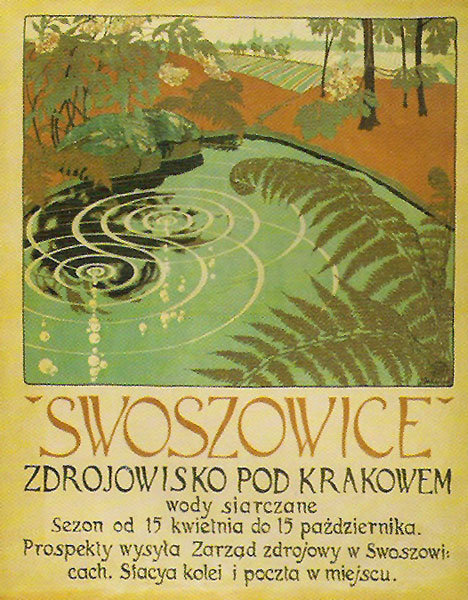

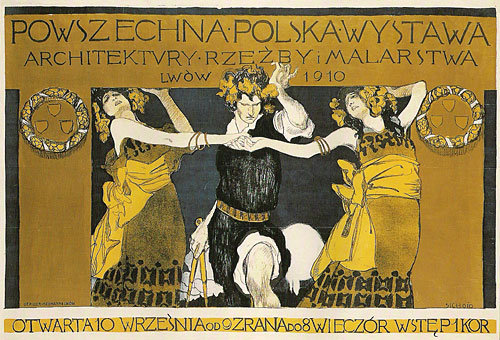

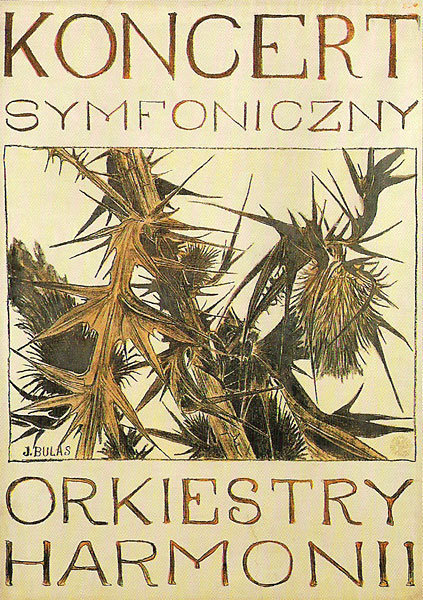

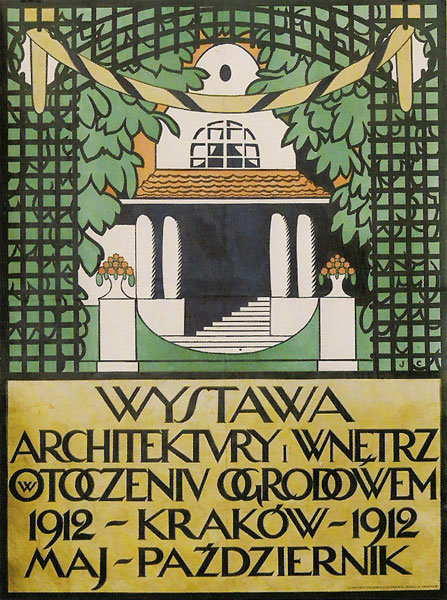

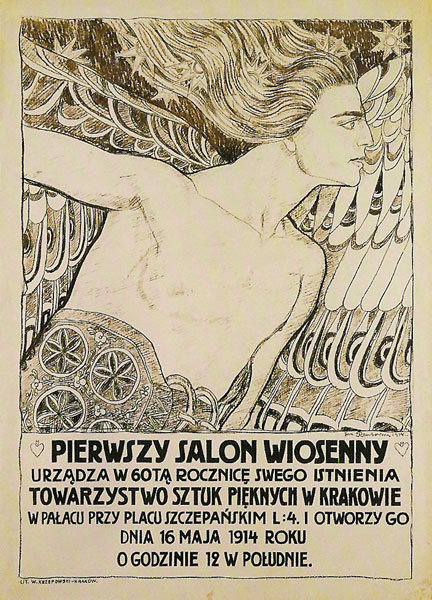

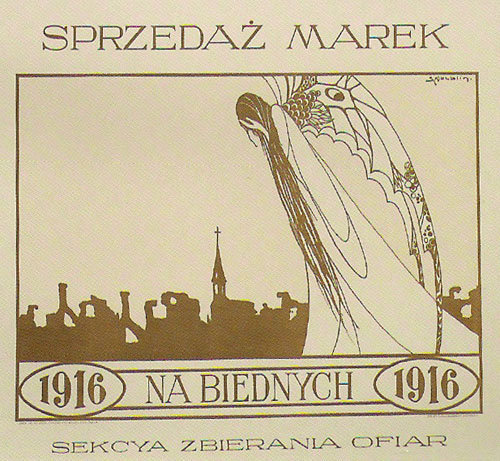

Toward the end of the 19th Century Poland was still absent from the maps. Its territory was split and controlled by Russia, Austria and Prussia. While Warsaw, then under Russian rule, was the biggest economic, trade and industrial center of the non–existent country, Krakow, under the less oppressive Austria, soon established itself as a cradle for artistic, cultural, scientific, political and religious life, becoming the ideal capital of the nation.

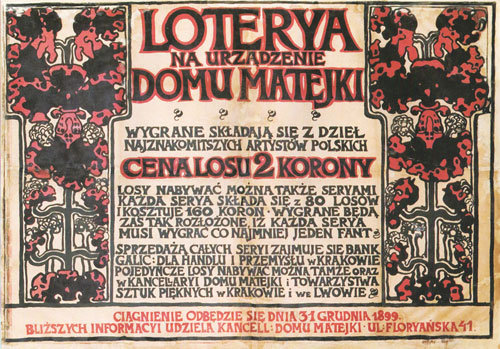

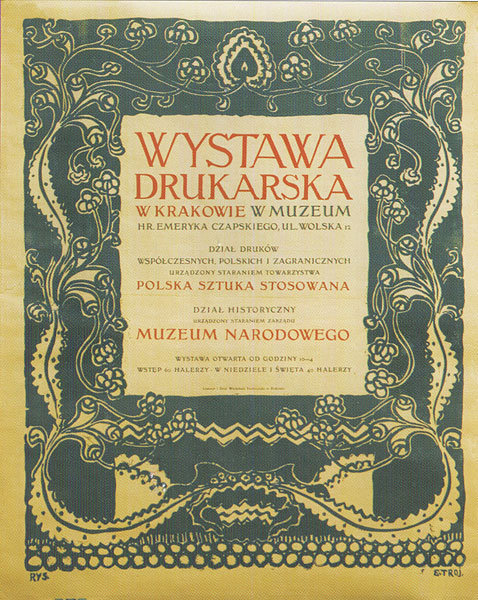

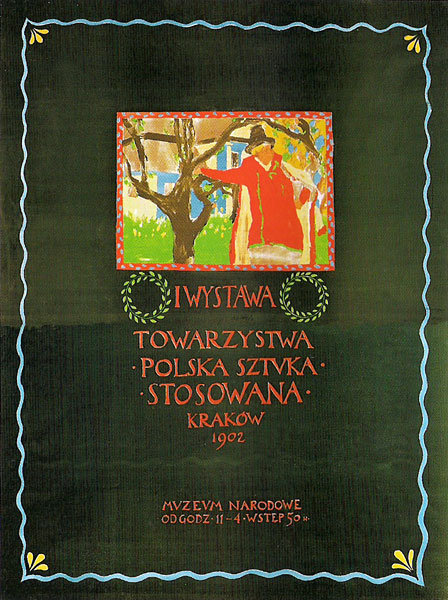

Krakow was populated by writers, poets and artists who had travelled Europe and had come in contact with the modernist cultural trends of the time. The poster had just been born in France at the hand of Jules Chéret following the invention of color lithography. Influenced by the achievements of the French masters of this new art form, Henri de Toulouse–Lautrec above all, these Polish artists chose the poster as the new medium of expression. They were well respected, connected with the Academy Of Fine Arts and members of the Society of Polish Artists “Sztuka” (Art). The poster thus became acceptable as a form of art.

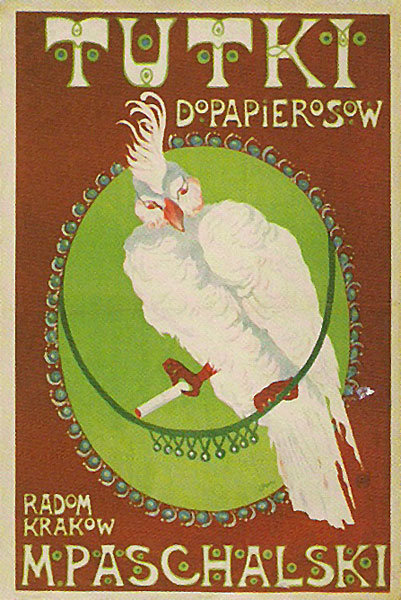

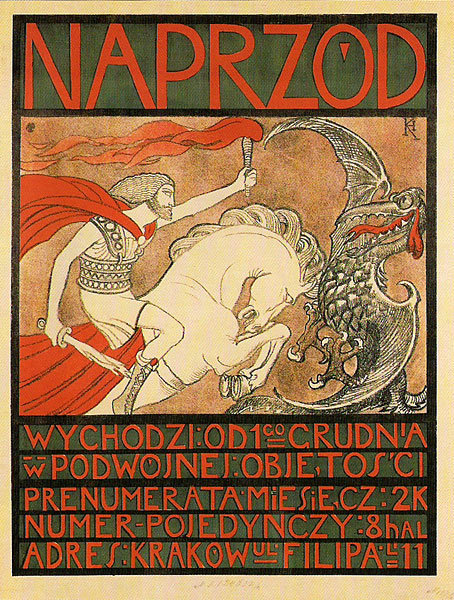

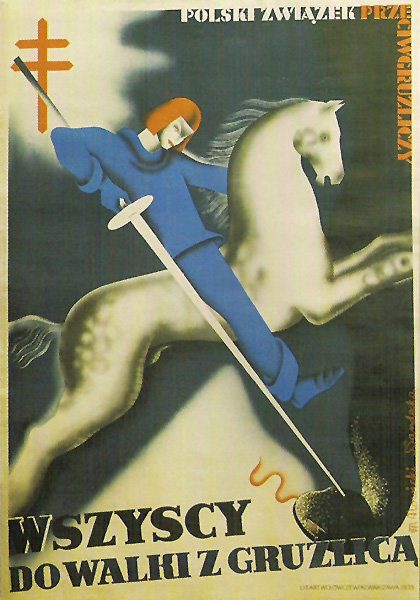

The first Polish posters appeared in the 1890’s at the hand of outstanding painters like Jozef Mehoffer, Stanislaw Wyspianski, Karol Frycz, Kazimierz Sichulski and Wojciech Weiss. Influenced by the Jugendstil and the Secessionist movements, understandably they painted posters that were art–related, announcing exhibitions, theater and ballet performances. Their work was vastly popular, which led to the first International Exposition of the Poster being held in Krakow in 1898.

Jugendstil, Secession, Japanism and modernist styles like Cubism were mixed with traditional elements of symbolism and national folklore. What set the Polish posters apart from their European counterparts was the emphasis placed on the highly artistic quality of the project, an attitude that will continue to characterize the Polish poster throughout the 20th century.

Jan Wdowiszewski from 1891 to 1904 was the director of the Technical Industrial Museum in Krakow. He was the organizer of the International Poster Exhibition in 1898, for which he wrote two essays, the first of their kind, entirely devoted to the art of the poster. He immediately recognized the power of the poster to act like a mirror for society’s physical and mental way of life. This was especially true of the exhibition posters, which promptly reflected every trend and influence coming from the West. The strong drive to promote the national style, as a means to a true political independence, was also faithfully recorded in the street art.

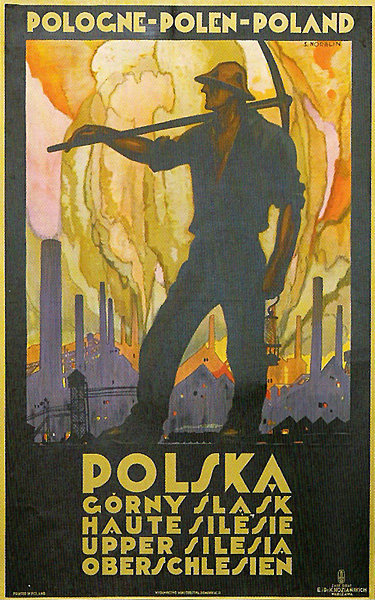

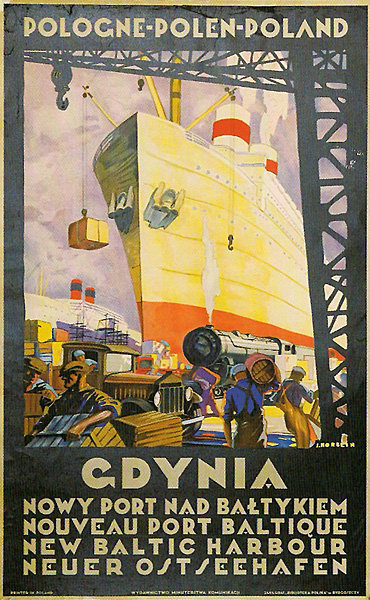

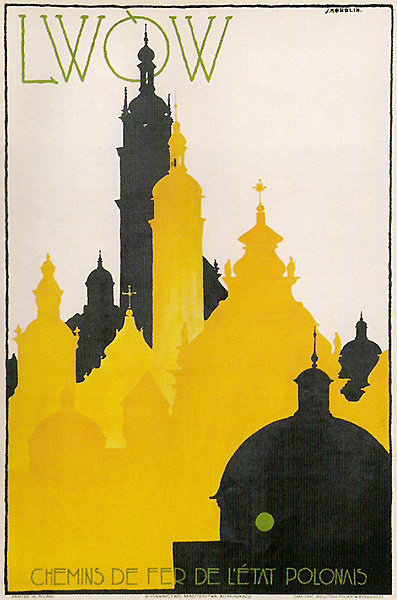

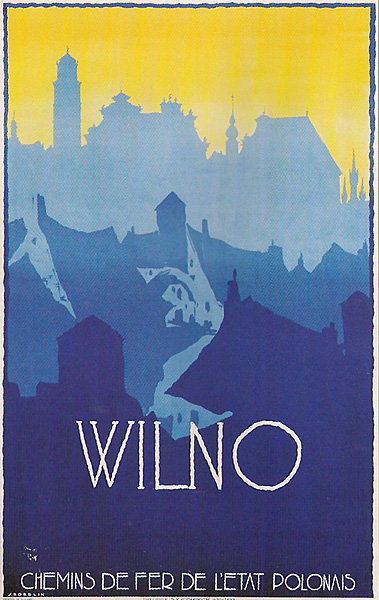

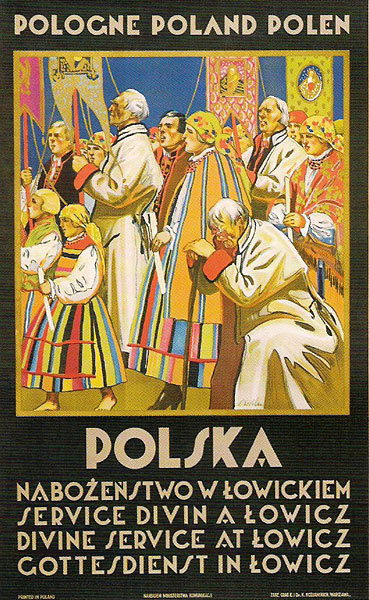

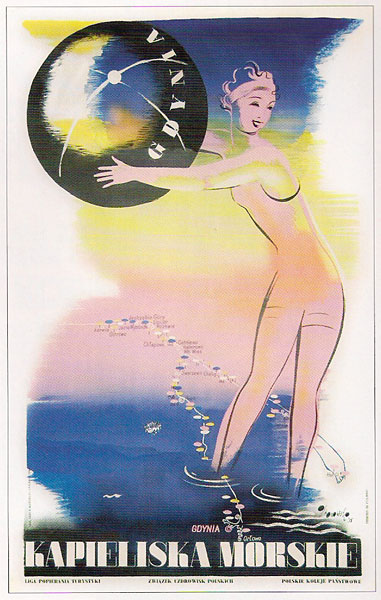

Stefan Norblin and the Touristic Poster

The period between the two World Wars sees Poland finally reappearing on the maps. The twenty years of independence are marked by a stunning growth in all industries. Tourism, especially, is at its height. Stefan Norblin is appointed to create a series of posters with the intent of promoting Poland as a tourist resort.

First and foremost a painter rooted in the school of realistic representation, Norblin approaches the poster the way he approaches the canvas. He makes use of obvious imagery to secure immediate reading from the viewer. Although characterized by recognizable forms and silhouettes, his works remain stunning for the stark choice of “neon” colors. They are not of an Expressionist nature but they create an irreal atmosphere around familiar objects. This and the minimalist style confer his posters a timeless quality.

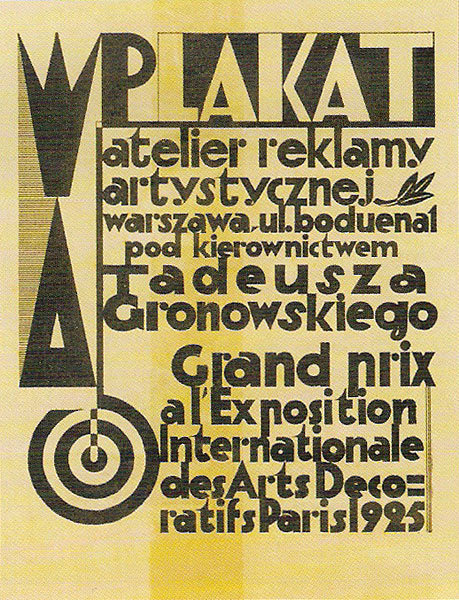

Tadeusz Gronowski: Father of the Polish Poster

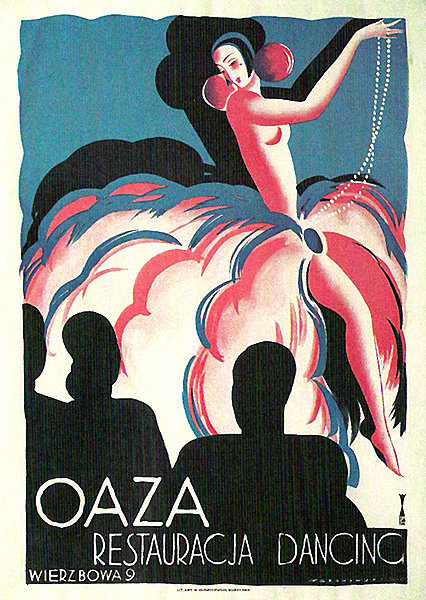

After the First World War Poland finally gained independence (1918). With it came a rapid process of industrialization and development of trade. The market was suddently saturated with different products hence the need for powerful advertising. The poster became its medium of choice. The advertising poster of the 1920’s and 1930’s differs from its highly elaborated artistic predecessors in that it utilises a simpler, more direct visual language to communicate with the viewer.

This was a requirement of the market made possible by Cubism, a style that forever freed art from beauty and ugliness, from the necessity to imitate nature. Architects, especially students from Warsaw University, were the most receptive creators of posters during this period. They were not weighed down by the academic ballast as were the painters of the previous generation. They were naturally inclined to apply the rules of geometry to commercial uses. It is among these students that we find the figure of Tadeusz Gronowski.

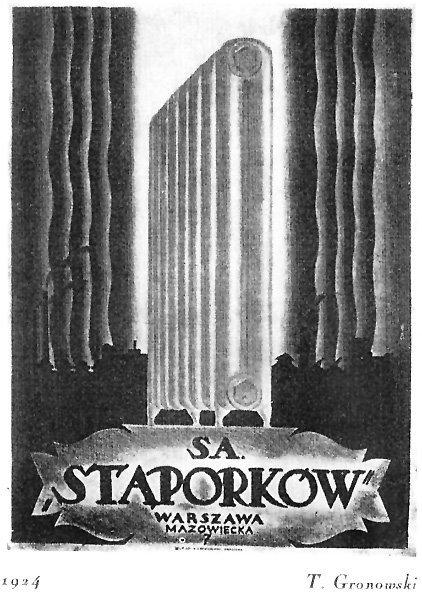

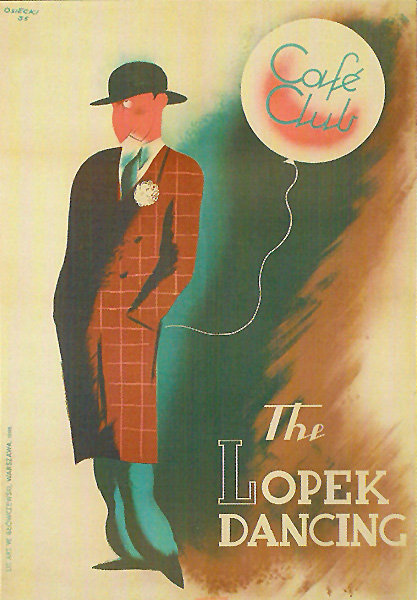

A gifted student, Gronowski was the first to specialize in poster art. Influenced by European art movements (he was well connected in Paris in the Twenties) he singlehandedly created the art of the Polish poster. Catering to the new necessities with which graphic art was confronted, advertising, he took advantage of the full spectrum of techniques available to the artist at the time to create the most striking advertisements of the period. His work shows a transition to the newest tool, the airbrush, resulting in softer lines and backgrounds. His advertising posters remain a milestone in the development of what came to be known as the School of the Polish poster.

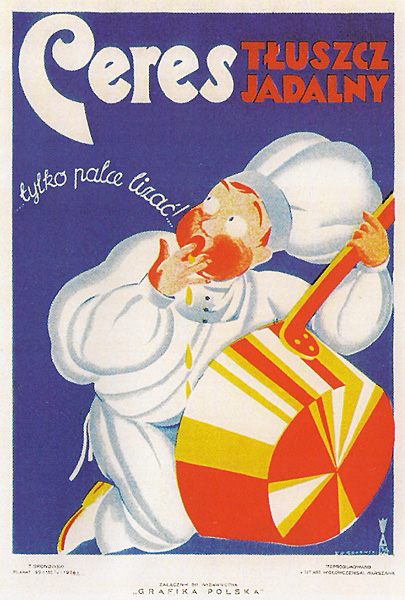

In contrast to Stefan Norblin, Gronowski, himself an accomplished painter, approaches the poster as a medium unto itself. Instead of merely adapting his painterly style to the poster format, he sees in it the opportunity to create something new, indeed a new form of artistic expression. He is one of the first artists to consciously integrate the typography with the illustration and instead of choosing the obvious he offers the viewer a different look into the subject, often displaying a penchant for the light and the humorous which endeared him to the viewers.

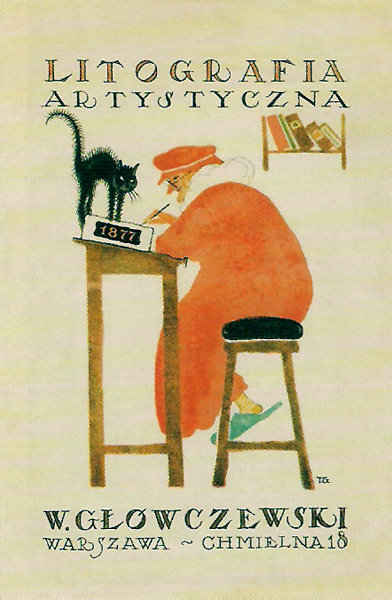

The next image portrays one of his earliest works. Even though the text is not incorporated in the image, the composition is clear. The cat and the artist’s faint smile add his trademark touch of humor to the painting.

A true master of the advertising poster, Gronowski blends the mundane with the artistic in a seamless composition.

Gronowski founded his own studio in Warsaw and aptly named it Plakat, i.e. Poster.

The next poster is particularly important in Gronowski’s production. An advertisement for a washing product named Radion, its slogan reads “It washes by itself.” The artwork is minimalistic and to the point: a black cat enters a bucket full of Radion and jumps out all white. A clear message amplified by the stark chromatic contrast and the essential lines.

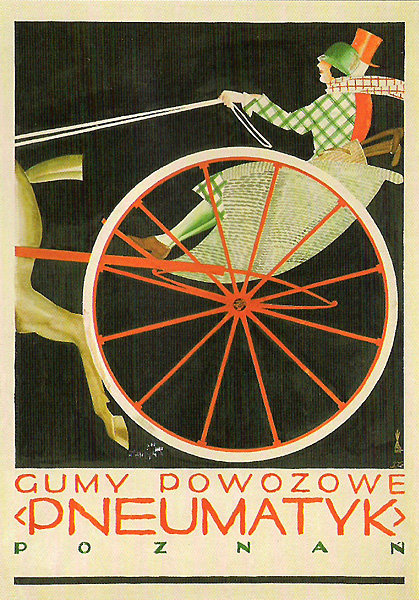

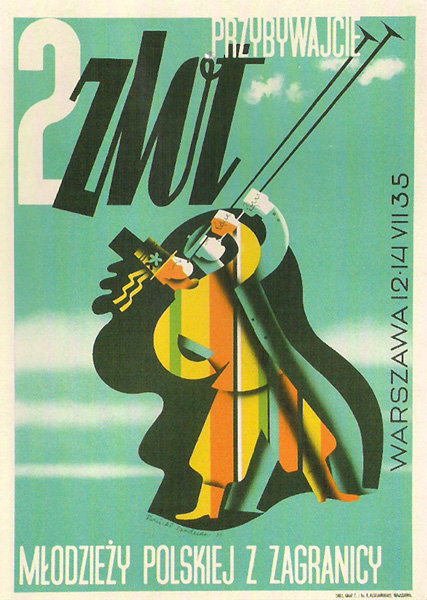

The next pieces exemplify the evolution towards integrated designs. The typography is part of the composition.

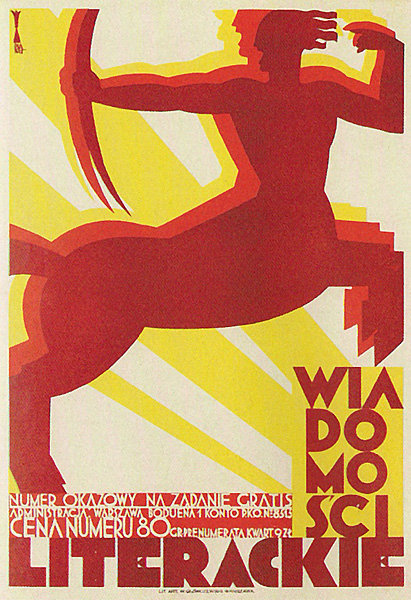

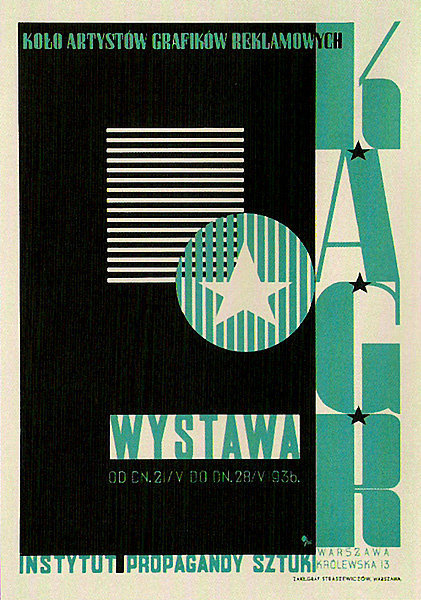

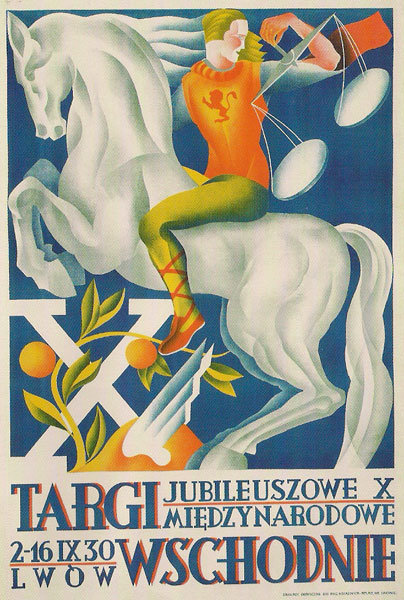

The Warsaw Architects

Gronowski’s work was continued into the Thirties by a group of architects educated in Warsaw under professors Zygmunt Kaminski and Edmund Bartlomiejczyk. At the University they learned to master the techniques of applied graphics. Architecture was seen as the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total artwork, the summation of all arts applied to a specific, practical function. Their hands–on approach lent itself beautifully in their transition from architects to graphic artists.

Responsible for this transition were economic reasons but also the will to work for contemporary society, which poster art was capable of immortalizing faithfully. Incidentally, these are the same reasons that today drive budding architects to graphic design: creating applied art with fast job turnarounds and satisfying economic turnover.

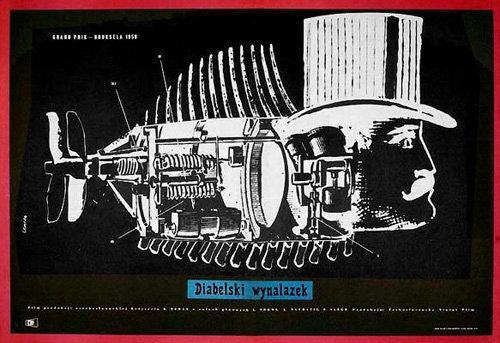

These architects turned graphic artists took Tadeusz Gronowski’s approach forward, combining it with a sense of composition and proportion naturally derived from their architectural background. Not only did they incorporate three–dimensionality in their works, they also adapted their style to the subject of the given poster, for example using a precise linework for posters depicting mechnical parts, humorous figures for posters depicting ballets and festive occasions and striking, dynamic compositions to illustrate sports events. Their work marks the transition of the Polish poster from narrative medium of the 19th century to modern advertising device of the 20th century.

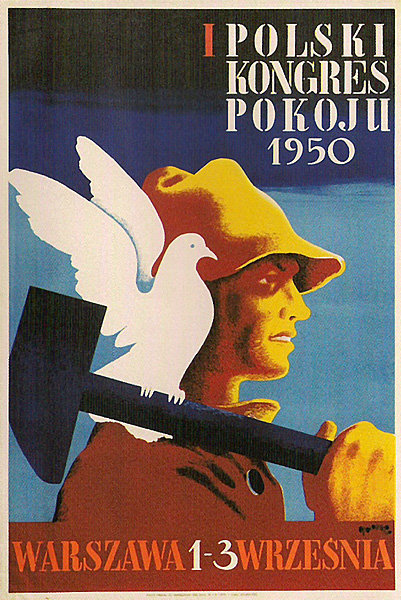

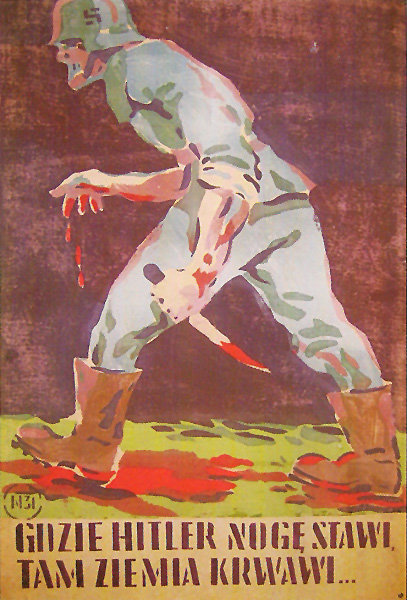

The Propaganda Posters

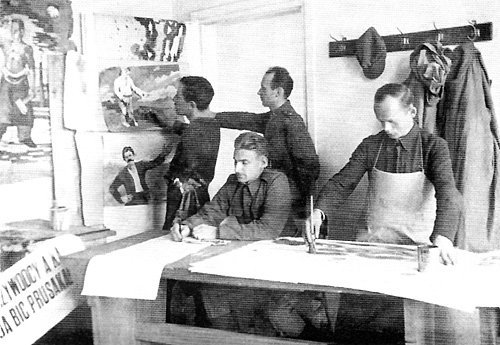

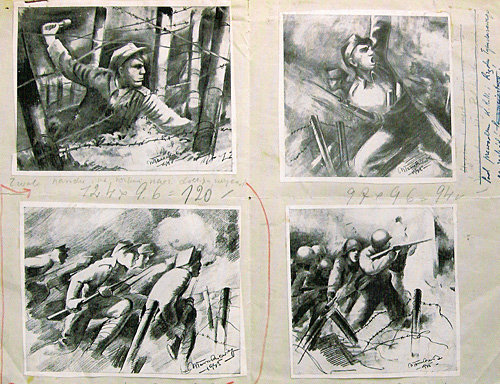

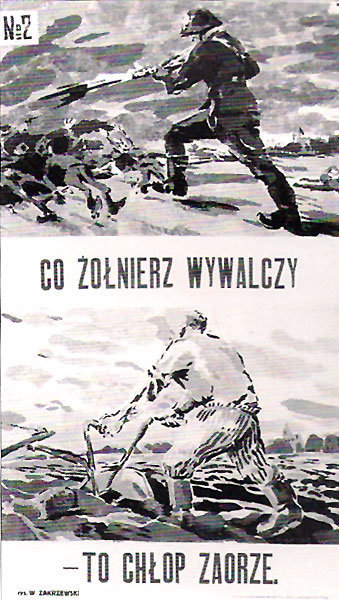

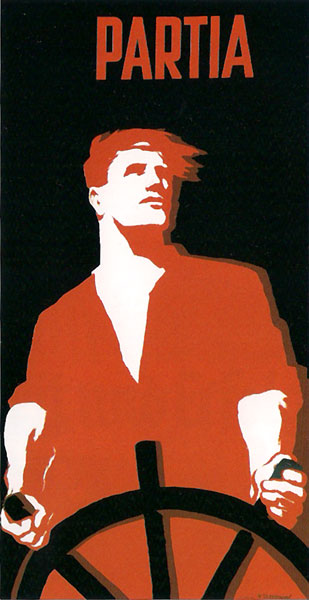

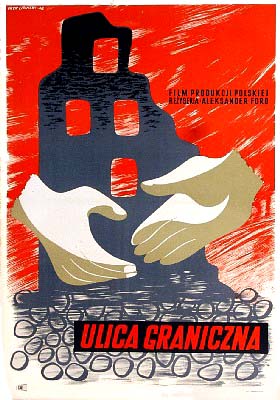

After World War II Poland found itself under Communist rule. The new government needed to spread the new aesthetics and make the new institutions acceptable to the public. With that goal in mind the Propaganda Poster Studio was established in the city of Lublin.

Wlodzimerz Zakrzewski was a talented landscape painter and active member of the Communist Party who had studied painting in Moscow in 1940 and had designed posters for the Soviet Propaganda. He was therefore the perfect candidate to run the Studio. The military introduced patterns of representation borrowed from the Soviet poster tradition, propaganda graphics connected with the TASS, the Telegraphic Agency of the Soviet Union. Zakrzewski was given a list of catchphrases assigned to the propaganda. His task was to devise graphical rules to create a working method for propaganda posters.

Zakrzewski aimed to introduce a new visual language by basing his colorful images on verified patterns borrowed from the stylizations learned in Russia. He also acted as mentor to a number of what were, in fact, unprofessional poster artists. This experience marks the first time poster art was institutionalized in Poland, giving birth to the proper phenomenon that followed, the “Polish Poster School.”

The 50’s and the 60’s: The Golden Age

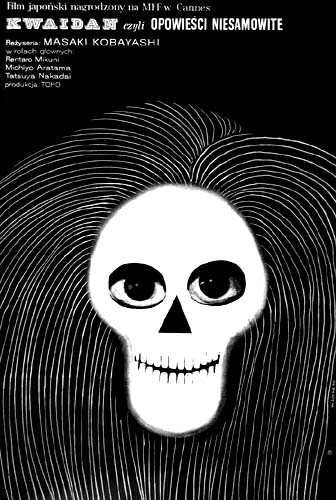

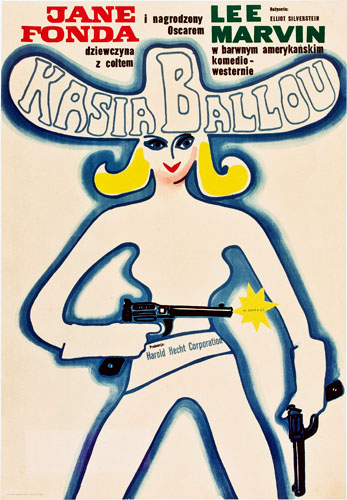

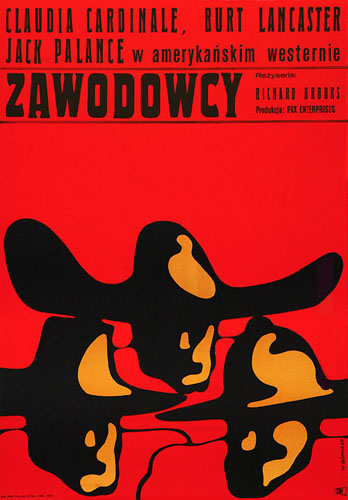

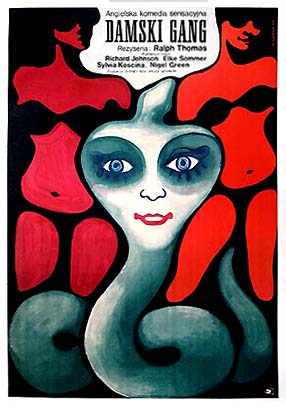

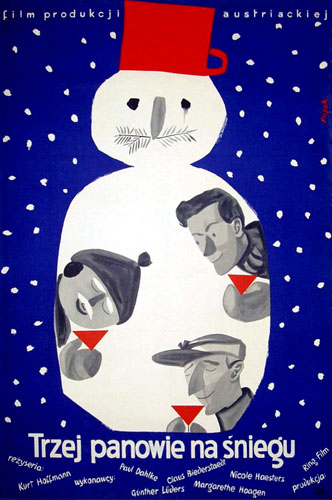

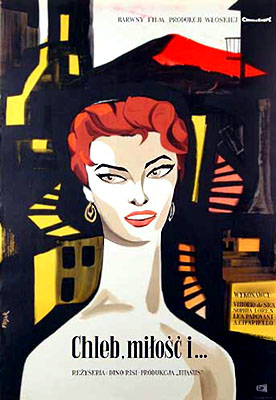

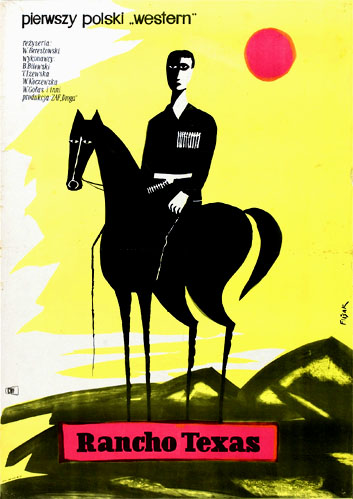

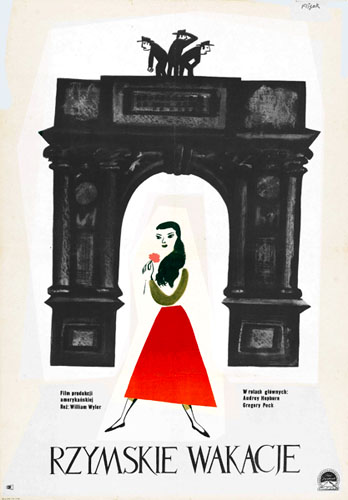

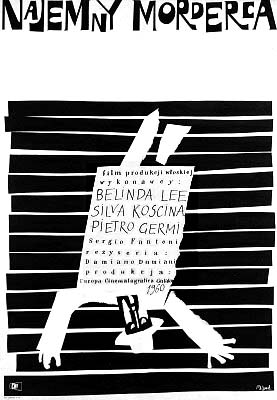

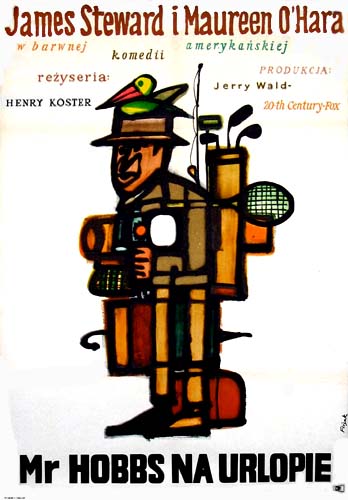

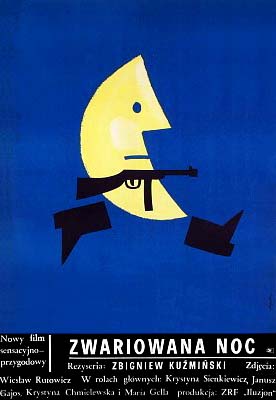

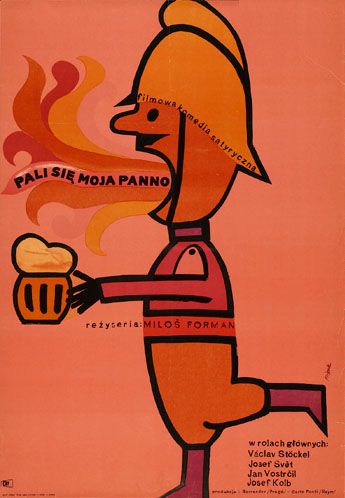

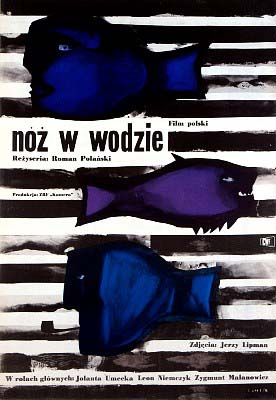

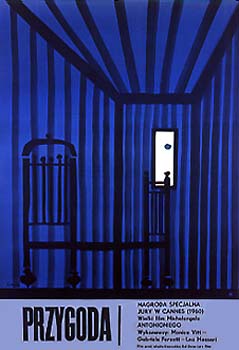

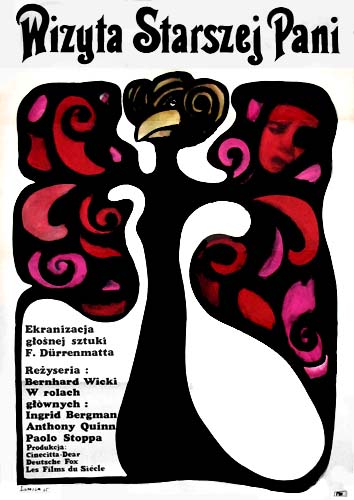

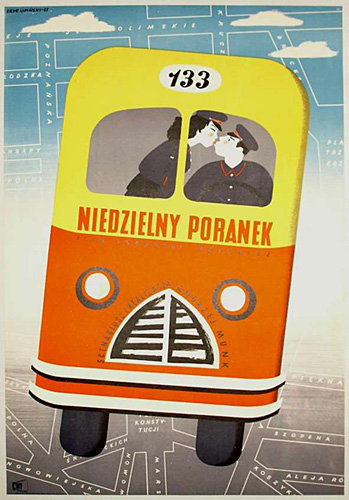

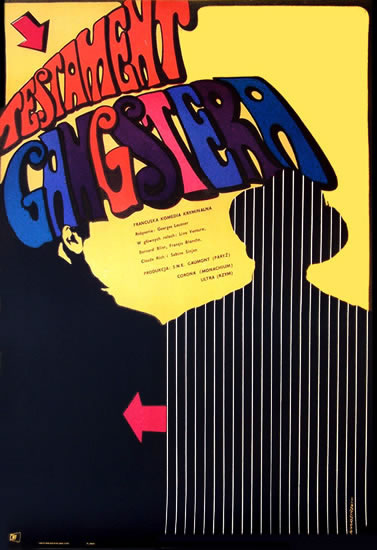

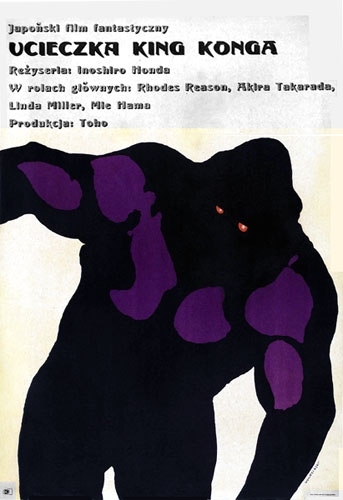

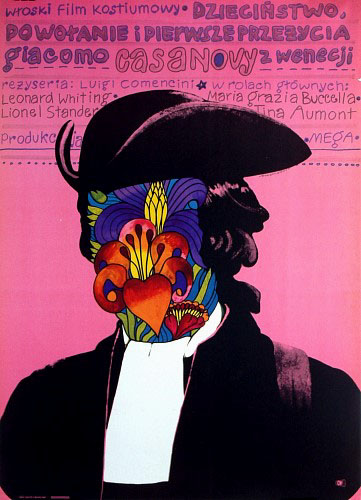

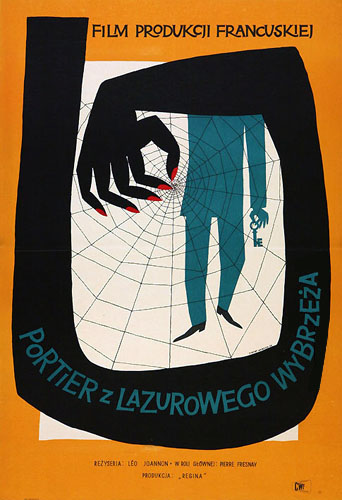

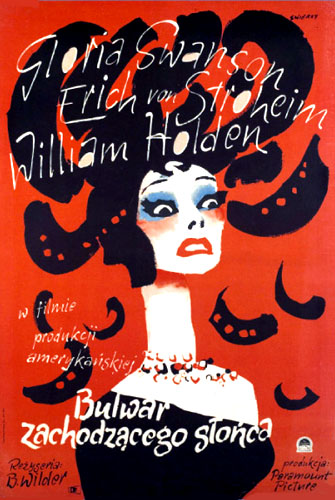

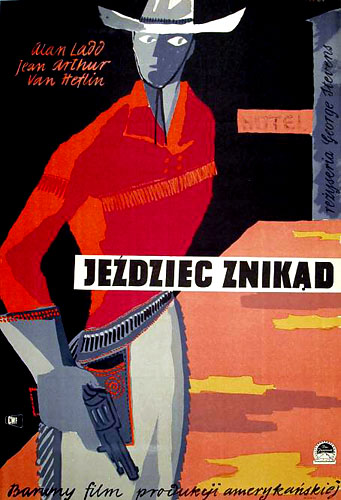

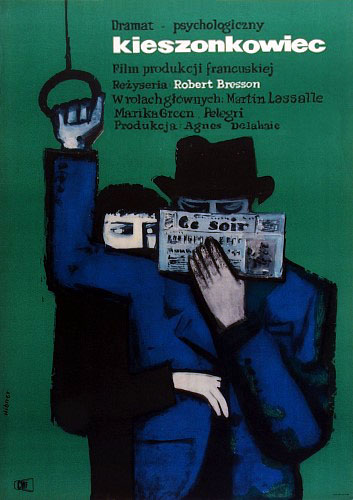

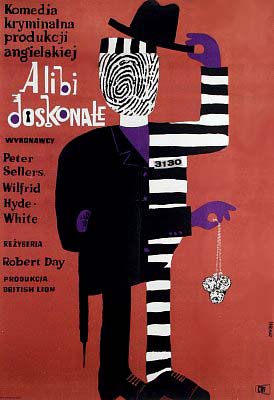

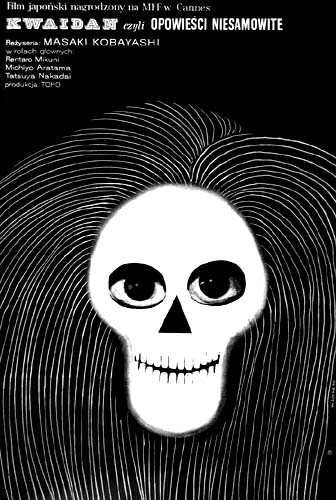

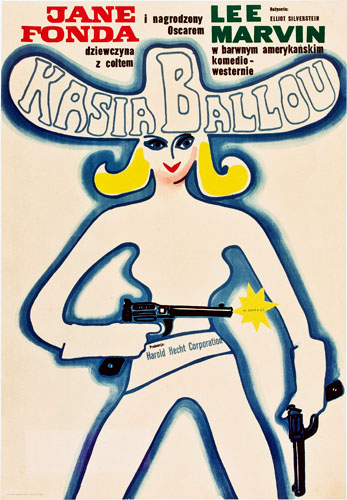

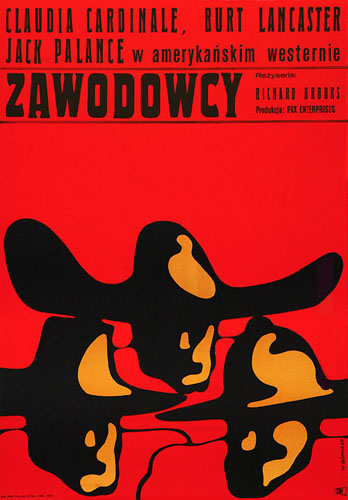

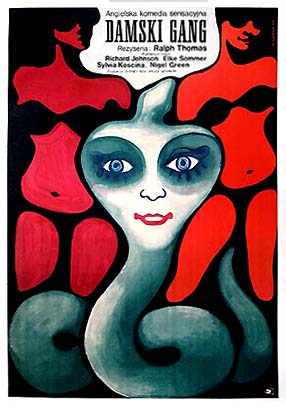

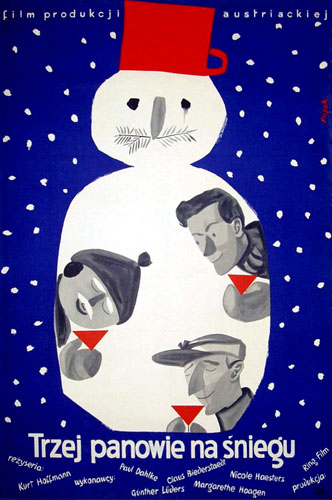

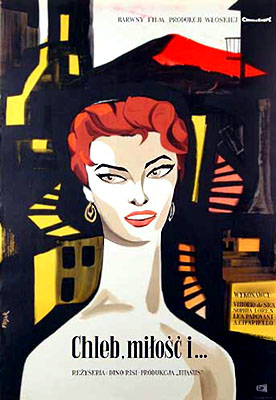

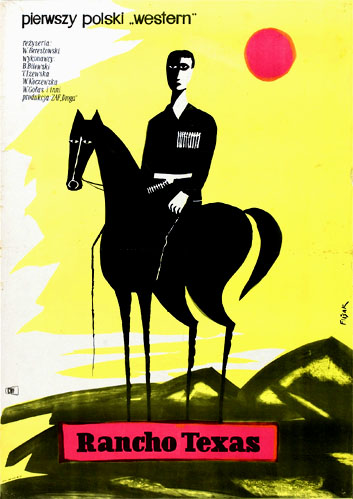

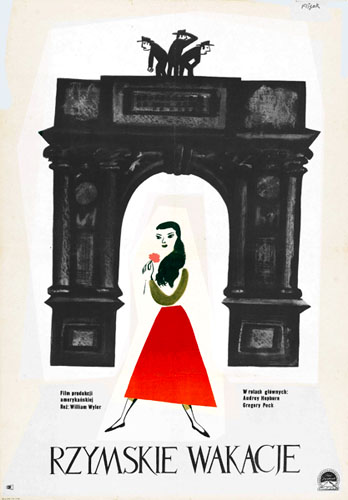

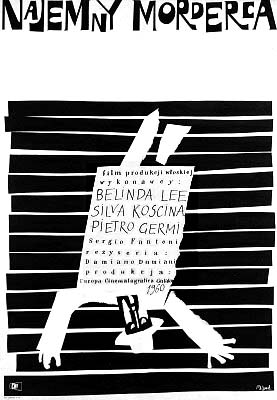

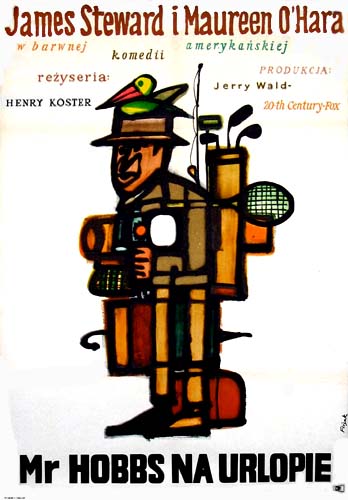

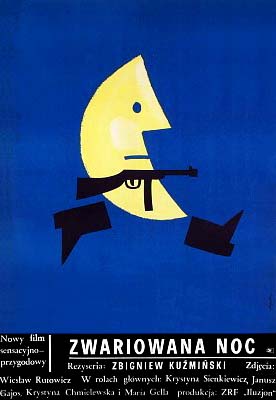

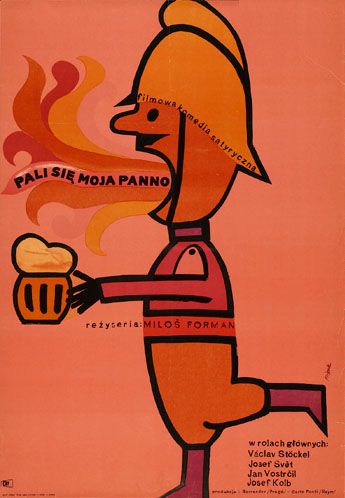

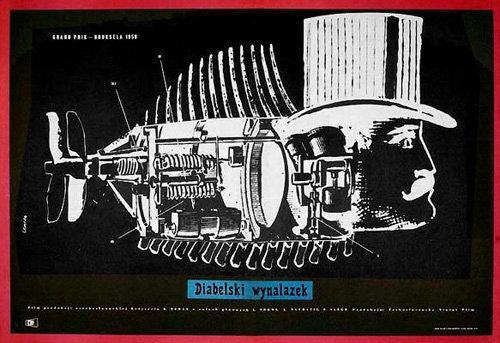

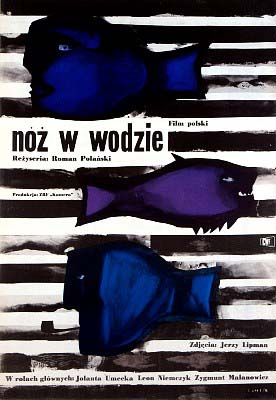

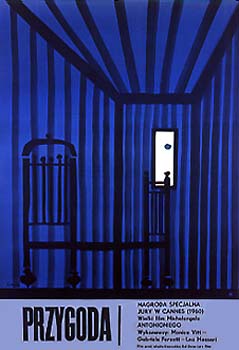

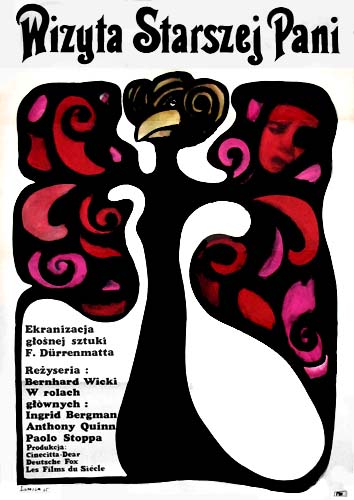

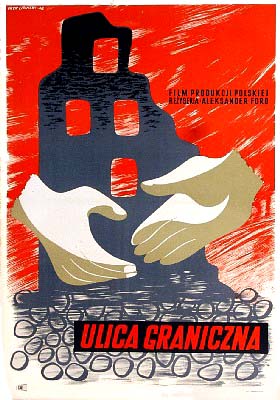

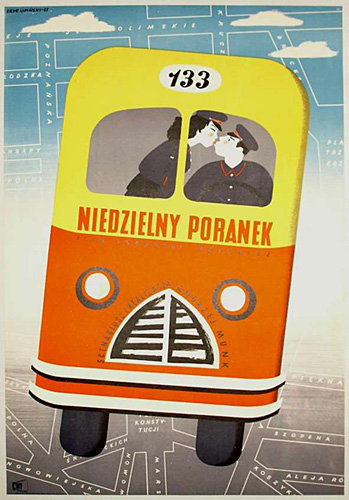

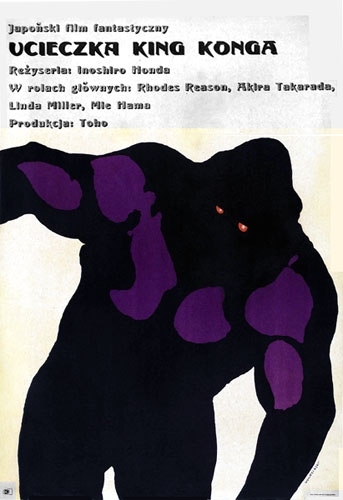

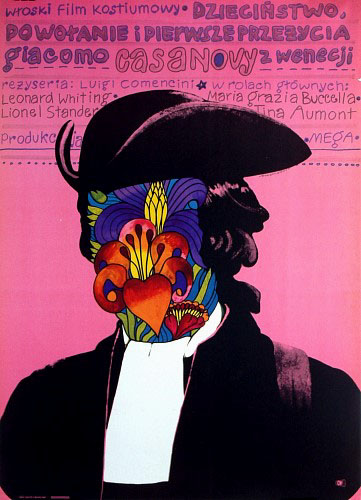

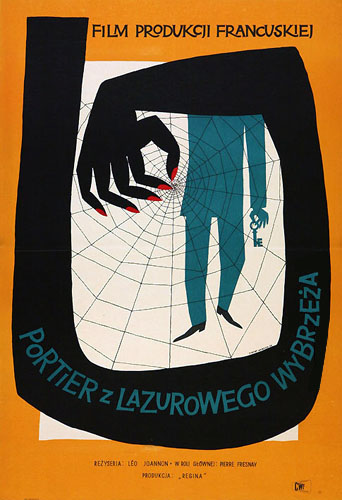

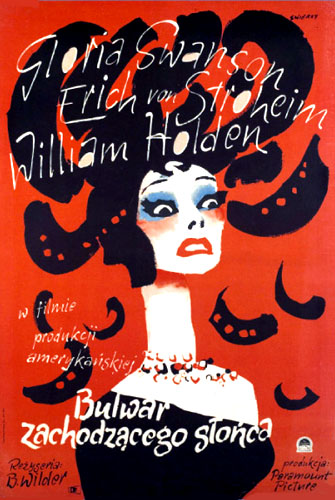

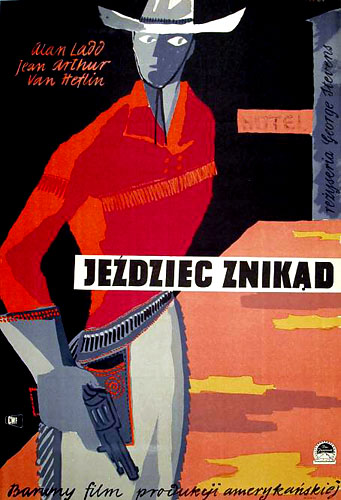

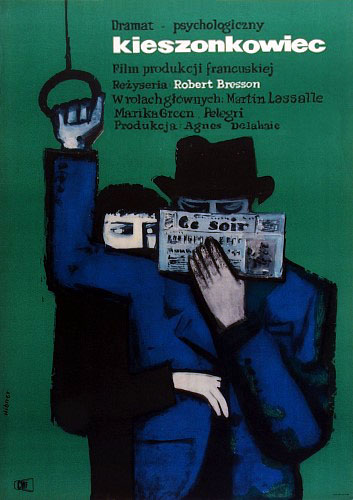

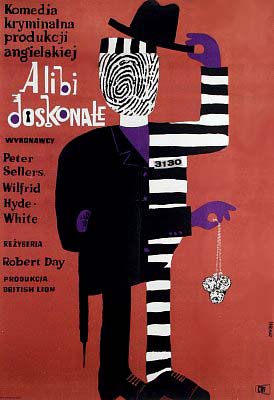

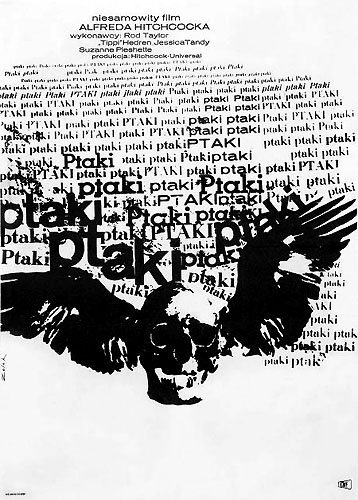

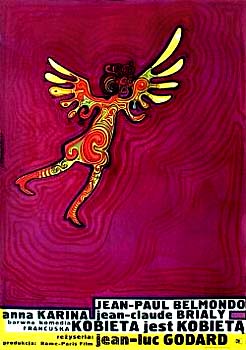

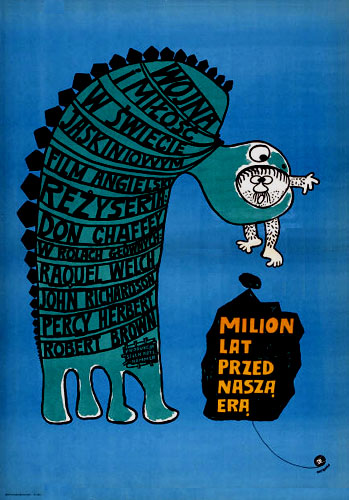

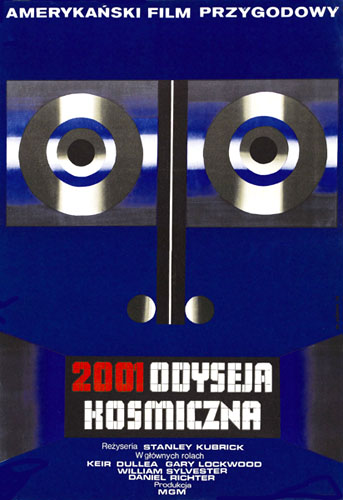

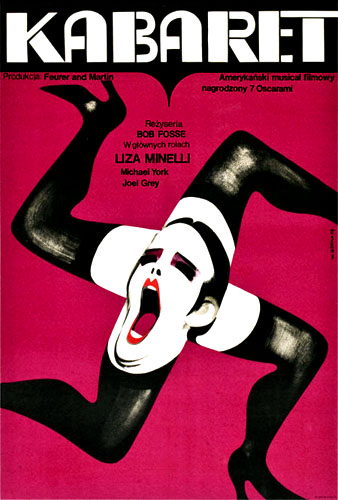

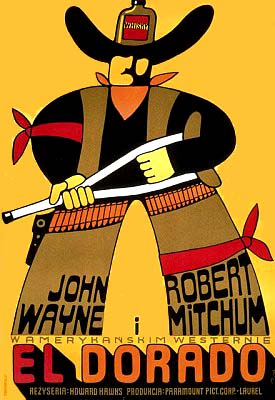

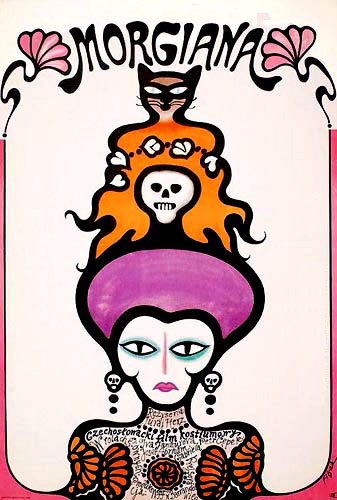

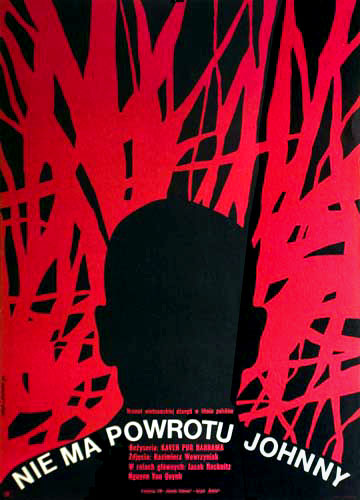

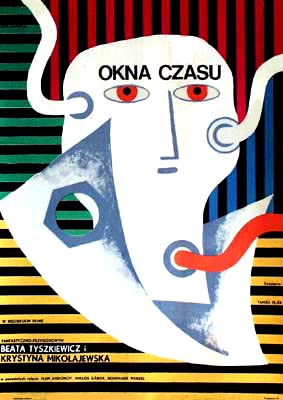

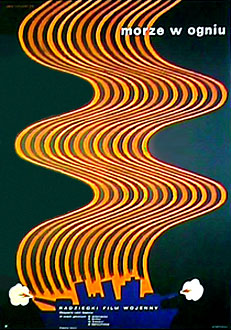

The Fifties and the early Sixties mark the Golden Age of the Polish poster. Like everything else, the film industry was controlled by the state. There were two main institutions responsible for commissioning poster designs: Film Polski (Polish Film) and Centrala Wynajmu Filmow – CWF (Movie Rentals Central). They commissioned not graphic designers but artists and as such each one of them brought an individual voice to the designs.

The School of the Polish Poster is therefore not unified but rather diverse in terms of style. It wasn’t until the Mid–Fifities, though, that the school flourished. The fierce Stalinist rule had been lifted, once again leaving room for artistic expression. The classic works were created in the next ten years. Three important remarks must be made. First, at the time the poster was basically the only allowed form of individual artistic expression.

Second, the state wasn’t concerned much with how the posters looked. Third, the fact that the industry was state–controlled turned out to be a blessing in disguise: working outside the commercial constraints of a capitalist economy, the artists could fully express their potential. They had no other choice but to become professional poster designers and that’s why they devoted themselves so thoroughly to this art.

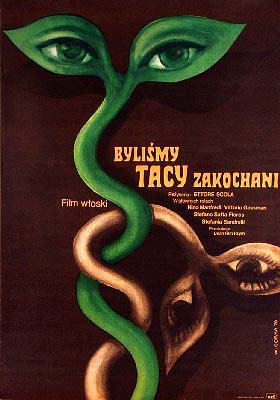

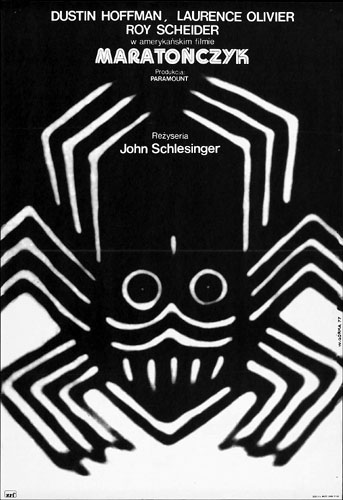

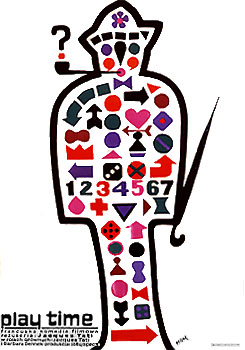

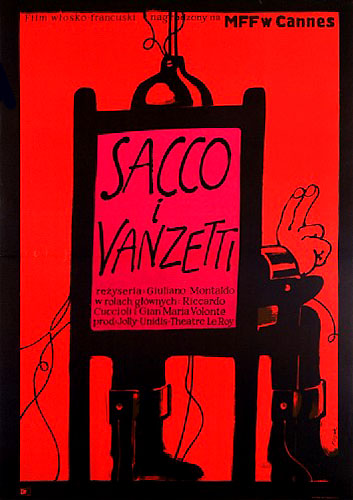

The Polish film poster is artist–driven, not studio–driven. It is more akin to fine art than commercial art. It is painterly rather than graphic. What sets the Polish poster apart from what we’re used to see in the West is a general disregard for the demands of the big studios. The artists requested and received complete artistic freedom and created powerful imagery inspired by the movies without actually showing them: no star headshots, no movie stills, no necessary direct connection to the title.

They are in this regard similar to the work of Saul Bass, a rare example of a Hollywood artist who enjoyed total freedom from the studios. Next to a typical Hollywood film poster with the giant headshots of the latest movie star and the title set in, you guessed it, Trajan Pro, the Polish film poster still looks fresh and inspiring today.

Without further analyzing a history that is best told in pictures let’s take a look at some of the many classic works created by the likes of Wiktor Gorka, Eryk Lipinski, Marek Mosinski, Jan Lenica, Jerzy Flisak and others.

Witkor Gorka

<

<

Jerzy Flisak

Jan Lenica

Eryk Lipinski

Marek Mosinski

Other artists

The 50’s and the 60’s: The Golden Age

The Fifties and the early Sixties mark the Golden Age of the Polish poster. Like everything else, the film industry was controlled by the state. There were two main institutions responsible for commissioning poster designs: Film Polski (Polish Film) and Centrala Wynajmu Filmow – CWF (Movie Rentals Central). They commissioned not graphic designers but artists and as such each one of them brought an individual voice to the designs.

The School of the Polish Poster is therefore not unified but rather diverse in terms of style. It wasn’t until the Mid–Fifities, though, that the school flourished. The fierce Stalinist rule had been lifted, once again leaving room for artistic expression. The classic works were created in the next ten years. Three important remarks must be made. First, at the time the poster was basically the only allowed form of individual artistic expression.

Second, the state wasn’t concerned much with how the posters looked. Third, the fact that the industry was state–controlled turned out to be a blessing in disguise: working outside the commercial constraints of a capitalist economy, the artists could fully express their potential. They had no other choice but to become professional poster designers and that’s why they devoted themselves so thoroughly to this art.

The Polish film poster is artist–driven, not studio–driven. It is more akin to fine art than commercial art. It is painterly rather than graphic. What sets the Polish poster apart from what we’re used to see in the West is a general disregard for the demands of the big studios. The artists requested and received complete artistic freedom and created powerful imagery inspired by the movies without actually showing them: no star headshots, no movie stills, no necessary direct connection to the title.

They are in this regard similar to the work of Saul Bass, a rare example of a Hollywood artist who enjoyed total freedom from the studios. Next to a typical Hollywood film poster with the giant headshots of the latest movie star and the title set in, you guessed it, Trajan Pro, the Polish film poster still looks fresh and inspiring today.

Without further analyzing a history that is best told in pictures let’s take a look at some of the many classic works created by the likes of Wiktor Gorka, Eryk Lipinski, Marek Mosinski, Jan Lenica, Jerzy Flisak and others.

Witkor Gorka

Jerzy Flisak

Jan Lenica

Eryk Lipinski

Marek Mosinski

Other artists

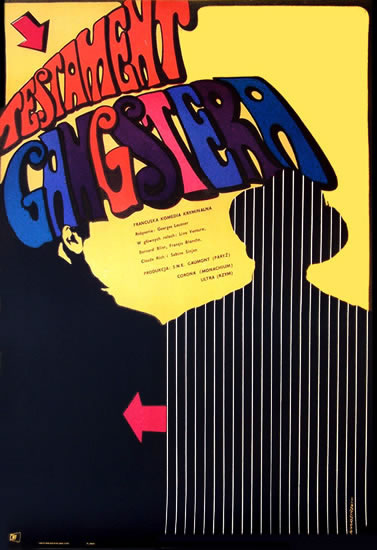

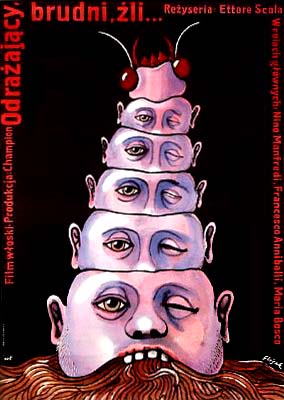

The 70’s and the 80’s: Decadence and Death

The School had its peak in the Mid–Sixties and during the following decade declined, much like art and advertising in the rest of the world. A few examples of posters from the Seventies follow.

Witkor Gorka

Jerzy Flisak

Eryk Lipinski

The Eighties were marked by society’s strong opposition to the increasingly oppressive Communist rule, exemplified by the Solidarnosc movement. Poster art quietly dwindled through the decade. After 1989, when film distribution was privatized, it died.

Nowadays alternative film posters are created by numerous artists as exercise and showcase of their abilities. Such posters are typically printed in small runs and viewed and sold exclusively in art galleries.

Conclusion

Posters are very important in the Polish culture. During the Communist regime they were probably the only colorful things one would see in the streets.

A small but dedicated market for Polish posters has emerged over the years. Driven by more than just nostalgia, its aim is the preservation of what is both testament of a cultural heritage largely unknown outside its borders and an immense source of inspiration for today’s young artists. These collectibles are not available in huge numbers but, due to their being relatively unknown, don’t command high prices yet.

Further Resources On Polish Posters And Design

Here’s a list of online sources to browse and even buy Polish posters. The stores are not listed for advertising purposes but rather because they provide picture galleries with details for each item.

- Wilanow Poster Museum The first Poster Museum in the world, opened in 1968 as a branch of the National Museum in Warsaw.

- Krakow Poster Gallery A small gallery located in downtown Krakow. Despite its size it has an impressive collection of originals and reprints.

- The Art of Poster Poster gallery located in Warsaw.

- Poster Gallery at Antykwariat Rara Avis Poster gallery from a recent auction. It features some well known and rare pieces.

- Classic Polish Film Posters Probably the biggest online collection of film posters. The gallery is well organized and includes very detailed information about each artwork. Invaluable resource. Most of the images and film data in the article come from this site.

- Polish Poster Shop A very thorough catalog with many artists.

- Film posters typeset in Trajan For comparison purposes. A collection of movie posters in the Hollywood studio tradition: big star headshots, predictable composition and typography. This type of poster has replaced the artistic output of the past decades.

- Rene Wanner’s Poster Page This gallery contains various collections og graphic design artists, among them are also Polish artists and designers.

A few bibliographical references:

- Piotr Rudzinski, curator “Pierwsze polwiecze polskiego plakatu 1900–1950” (2009) A collection of essays by various authors about the development of the Polish poster. The emphasis is on the first half of the 20th Century. The essays are veru well researched and read like master’s degree papers. Includes many of the posters presented in this article.

- Anna Agnieszka Szablowska “Tadeusz Gronowski – sztuka plakatu i reklamy” (2005) A monography of the master. Includes 189 eproduction of his works.

- Krzysztof and Agnieszka Dydo “PL21, The Polish Poster of the 21st Century” (2008) A book about the contemporary poster scene. Created by the owners of the Krakow Poster Gallery.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Showcase Of Web Design In Poland

- 40 Exquisite Independent Film Posters

- 60 Concert Posters From Ten Amazing Artists

- 50 Beautiful Movie Posters

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st