Most Common Mistakes in Screencasting

When people think about how to start screencasting, they often forget that screencasting is not only a very interesting way of showing something quickly, comprehensibly and easily; it’s also a way of advertising their products. It’s a shame to see how many websites out there lack a beautiful looking screencast, as this can make products look a lot more attractive to potential customers.

What most hobby screencasters don’t know, is that screencasting is not simply the act of sitting down and recording the screen; simple screen recording was something we did four to five years ago. Screencasts have a long history, starting from “I just record my screen” to the fancy product demos you see today. Nowadays, a screencast is almost necessary for start-ups and new products, especially in the tech business

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Screencasting: How To Start, Tools and Guidelines

- Talks To Help You Become A Better Front-End Engineer In 2013

- Making Embedded Content Work In Responsive Design

My career as a screencaster started a couple of years ago. By that time, I was already blogging; sitting in front of Ableton Live (which I found to be a very original new workflow), I asked myself: what would be the best way to show others what I’m doing? The answer was clear: to record my screen.

That same night, I started using Snapz Pro X. My English was terrible and it felt awkward to record this thing — then to re-record it about ten times. Since then I have recorded hundreds of screencasts, including for Mac OS X Screencasts. Having gained a lot of experience, it’s now time to share this experience with others.

How Not To Do a Screencast

In the early days of screencasting, there were a lot of YouTube videos which now look like screencasting “dinosaurs.” This was to be expected then, but there are still people making the same terrible mistakes we all made in the early days.

Handheld Cameras

We probably all know that scenario; we’ve found a new function that apparently nobody uses in a program, and are so excited that we instantly want to share that idea on YouTube. It’s easy to grab a video camera or mobile phone and just point it at the computer screen, right? No. Never ever do that, as the videos will look terrible!

On the other hand, if the video shows something really, really extraordinary, people will watch it anyway. Content is king! If that video ends up on another website that showcases a product or service, it’s obvious that someone should invest precious money in screencasting software.

Facial Cameras

We have seen this a lot of times around the Web: screencasts with a smaller rectangular screen showing the person recording the screencast. Most of the time this screen is put somewhere in the video, and is always on. Even famous people like Merlin Mann are doing it. Merlin is great, by the way, although he’s no professional screencaster; all he intended to do was show his cool new workflow in TextExpander, which is great. Recording with built-in cameras is great too, but as I will describe later, use these functions wisely.

Consider the following:

- Is it necessary for a face to be there all the time?

- Does the audience really need to see a face to follow the screencast?

- Will the face distract people from watching the screencast?

I agree that for introduction purposes, it’s a good idea to show someone on a built-in or external webcam; but as soon as we move to the main content, it’s a good idea to fade that video out. In my latest screencasts, I do exactly that: at the intro my facial camera is on while I tell my audience what they are about to see — and then when I get to the first section, I fade this video out.

Here’s a recommendation: do a big close-up as your introduction, centered on the screen. Then say something like, “Hi, my name is Andreas and today I’m showing you Whatever™ product by Some, Inc. Whatever™ is great, and I love it; you will love it too, and here’s why.” Right after “…and here’s why,” either fade the video out or decrease the size of the video while moving it to the lower right/left corner. Then, leave that video a couple more seconds on screen before fading it out completely.

Distractions During Screencasting

When I started recording screencasts, this was one of the hardest things to learn: leave the mouse pointer wherever it is on the screen and don’t use it as an extension of your hand. If you own good recording or production software, callouts or zooms and pans are better tools to emphasize a particular thing on screen. It’s not necessary to move the mouse while describing something. Also, when you are editing the screencast later on, it’s much easier to make your edits when the mouse stays still so there is no distracting mouse movement between shots, or mouse jump at a jump cut.

On the other hand, the mouse pointer has to be used at times as it’s the only thing people can focus on to follow detailed instructions. Just using keyboard shortcuts is a bad idea. I would recommend on first showing, that you display the menu entry and point out that there’s a keyboard shortcut. On the second showing, use the shortcut (please do tell the listeners prior to execution, otherwise they won’t be able to recognize what you just did).

Don’t Annoy People

A crucial part of a good screencast is entertainment, a fact that many people — especially beginners — don’t realize. Someone watches a screencast to get information, but why not make it a pleasurable experience? Try to create interest by using animations and other techniques.

Another thing to keep in mind, is that there are some things a screencaster can assume: for example, that people can read and have used computers before, so they know how to click on parts of the screen and they know how to write.

In an online review of Snowtape, a Web radio recording application for Mac, the screencaster reads (starting at 0:38) every menu item in the Preferences. You don’t need to do that. Aside from being boring, the screencaster loses precious time for the screencast. On YouTube, a video is usually limited to ten minutes in length. (Pro tip: I have successfully uploaded videos which were 10:50 without getting rejected.) Just going through every single menu entry cost the presenter two minutes of precious time! That means only eight more minutes to show the rest of the application.

Some of my clients refuse to upload their videos to YouTube: Why should one want to upload a video to YouTube, rather than hosting on their own website? Creating a chic, customized Flash video player and all that stuff is fun, isn’t it? There’s one main reason why that’s not a good idea: YouTube is one of the biggest video websites we currently have on the Web. It attracts millions of users daily and has an embedding feature. Think of all the thousands of blogs out there. Creating a player just for one website is attractive, because the owner remains in control over the design and the video itself, but on the other hand, disallows and discourages their product from getting mentioned in — for instance — Smashing Magazine.

I would recommend staying within YouTube’s length boundaries not only for the sake of uploading a screencast, but also for the sake of audience attention span. Audience attention span seems to be gradually decreasing, which is another reason to keep a long story short. Common lengths for screencasts:

- Instructional (tutorial) screencasts: 8 – 10 minutes.

- Advertising videos: 1 – 4 min.

Preparing Yourself

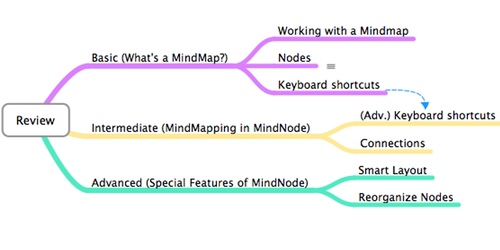

My recommendation is to write your script before an actual recording. I have found mind maps handy for this job (I’m a big mindmap fan anyway and use it for all kinds of things, like planning; sorting; thinking).

A screencast should have structure, but don’t “overplan” recordings either as it will suck the spontaneity out of your screencast. Sometimes, meticulous planning and sticking to your script is necessary to make a very straight-to-the-point screencast. However, in most cases keeping everything natural for the audience is the topmost goal. My recommendation:

- Don’t try to sound unnatural by using overly complicated vocabulary. Keep it simple. Use spoken language. (No curse words!)

- Try to follow the path laid out in the script, but feel free enough to make spontaneous remarks here and there. The audience will appreciate it! As I said before, they want to be entertained. Don’t try to sound like an over-enthusiastic moderator. You’re not! You won’t sound like yourself and your audience will switch off!

- Organize in sections rather than trying for a single, long take. In most cases you may have to re-record several times, often because some little details didn’t work. This can cost you a lot of time, so dividing your screencast into sections makes recording much easier.

Sometimes, meticulous planning and sticking to your script is necessary to make a very straight-to-the-point screencast.

Sometimes, meticulous planning and sticking to your script is necessary to make a very straight-to-the-point screencast.

Sections should be three to five minutes each. After recording each section and saving it, import each section and put a transition between them. This is not only easy to do, it looks great, and helps the audience follow the screencast as they know that a new section begins when they see a transition.

One thing to keep in mind: use simple transitions over the fancy ones! Don’t think “awesome” transitions will also make a screencast look awesome. A bad screencast will not get a cool, fresh look from cool-looking transitions; what’s recorded, is recorded. Try to stick to the simple things; cross dissolve or dip through black, and if it has to look “flashy,” dip through white.

Division

When planning a screencast, I most often create three chapters:

- Beginner

- Intermediate

- Advanced

Beginner

In the Beginner part, I talk about the basic functions of a program.[1] I tell my audience who I am; what they are about to see; what this application is supposed to do; who made it; and so on. After this short introduction I show a simple, short workflow demonstrating what the application was made for. This, again, draws people’s attention to the screencast: “Hey, that looks really useful. I’m doing that a lot. Maybe I should continue watching.” Then, the Intermediate part begins.

Intermediate

After an introduction and showing some basic functions, it’s time to go into detail:

- What else does this software have to offer?

- What are the functions a user discovers at second launch?

For example, for a text editor I focus on functions that make this editor stand apart. I might talk about software interface, shortcuts and useful functions — basically, the things users discover after the second or third time they launch the application.

Advanced

When it becomes clear what the application does, I then concentrate on showing the really advanced stuff. You have reached your goal when people think: “Wow! This is crazy! I didn’t even think that would be possible with this. I really need to check this out!” Maybe, it’s an export function nobody thinks of; or, a hidden preference setting somewhere. Who knows? This is why it’s so important to be well prepared and to be familiar with the product; for example, I recorded a screencast on how a very simple stop-motion app named Smoovie can be used with AppleScript and Automator to record time lapse videos.

Screen Recording Software

People often wonder what screencasting tools are available, and how to decide on one or the other. Although some tools are already mentioned in the article Screencasting: How to Start, Tools and Guidelines, I want to make a short addendum to this list. Since the release of Snow Leopard, QuickTime Player is also capable of recording the screen. Although it leaves an icon in the top-right of the screen, this is probably the cheapest solution.

Using simple “screen-record-only” software has the downside that you need to find other software to edit your video; this means, again, a bit more time and effort. If someone wants to take screencasting more seriously, I would recommend ScreenFlow or Camtasia. Both are well equipped “editing-and-recording-all-in-one” solutions able to handle everything needed for a good screencast. They have layers, editing tools, callout functionality and more. Most screencasters edit on ScreenFlow or an equivalent before exporting the video to Apple Final Cut or Adobe Premiere, where lower-thirds, transitions or a table of contents are added (this is the workflow of Don McAllister, for example).

Animations (Using Zooms, Pans and Callouts)

A common mistake among screencast newbies is not to make use of the zoom and pan functions. While I recommend their use, there is a slight difference between using and overusing.

Zoom

New screencasters often don’t use zoom [2] at all, but don’t be afraid to zoom in to show something with bigger detail. In a standard ten-minute screencast, often all I see is someone else’s screen; a moving cursor is all that changes, or maybe some windows pop open or a checkbox gets ticked. Wouldn’t you feel totally bored watching a moving mouse cursor move for ten minutes? I have had clients saying they want exactly that. Honestly, although I usually enjoy hearing myself talk, watching such screencasts makes me sleepy.

Zoom in on a detail, talk about that function, and then zoom out or pan to the next function.

Zoom in on a detail, talk about that function, and then zoom out or pan to the next function.

So, make use of the zoom function to make a screencast a bit more exciting. Zoom in on a detail, talk about that function, and then zoom out or pan to the next function. That way people see a more dynamic visual change, which creates interest and holds peoples’ attention. As with other things, like callouts, this function should be used wisely: not wherever possible, but wherever useful.

Pan

While zoomed in on a detail, the audience can’t see everything outside the cutout. Pans are useful to move the “camera” around — while remaining zoomed in! I use pans when my (mouse) cursor is about to move out of a cutout area. I try to move the camera along with the mouse pointer; that way the pan action looks very natural and seem to make more “sense” instead of moving the camera first, and then the mouse.

As a rule of thumb, choose the solution you think makes more sense to a person watching your screencast. Always consider the audience! Standard pan lengths, as well as standard zoom lengths, can get annoying as they are very repetitive. Professional screencasting applications allow you to customize the length of an action. Make use of that possibility!

Callouts

As an example of what not to do, a common mistake is to have the checkbox in ScreenFlow which says “Show modifier keys when pressed” enabled during the entire screencast. Another checkbox says to display mouse-clicks as Radar, or to make clicks audible. These options are not bad, but again, overusage is not a good thing; people intuitively know that when a window comes to the foreground, someone must have clicked on it, so why bother them with a stupid effect?

On the other hand, when saying something like: “…and when this checkbox is enabled, the app automatically does such-and-such…”, it’s a good idea to turn on visual click effects. Split the clip before the click happens, then split the clip afterwards, and enable click effects for this new separate clip. Done! Probably the best tip for you: use effects to support your explanations, not as something fancy to have. When I realized this, it changed my whole way of doing screencasts.

Overlays And Lower-Thirds

When all the edits are made, it’s a wise idea to add a bit more of that extra magic to the video such as a table of contents or lower-thirds. The options here are wide open. Although professional apps like Camtasia offer mandatory support for animations, they are no power houses in that regard. Try to find another application to create those overlays and import them to your screencast.

An animation program needs to be capable of producing transparent movies, which are added as a separate layers on top of the screencast. I create mine with Keynote, which can export transparent movies using the Share function. Go to Share > Export. Then select Custom… in the Formats drop-down menu. Make sure to enable Include transparency. I use the Apple Animation codec for exporting.

Apart from Keynote or even Linux software, and if you want to invest a bit more money, Apple Final Cut Pro’s Motion; Adobe After Effects; Red5, and a lot of other programs are specialized for creating these effects. Most screencasters I know use the Apple Final Cut Pro Suite, where Motion is included. Others stick with After Effects. Both are professional, advanced tools.

Recording Equipment

The audio quality of a screencast is often determined by the hardware used. Many people use their built-in microphone on a laptop, which is fine most of the time but has several downsides:

- People will hear you typing and clicking.

- The recording will have more hiss, because of the poor microphone quality.

- The recording will have more ambient sound (such as a printer printing, the phone ringing, the wind blowing or a car honking).

Buying a good microphone is another steep investment, but it’s definitely a good one that adds a lot of value to your recording equipment. Sure, for me as an audio engineer, it’s quite easy to pick the right set of equipment. But newcomers often have problems with this. The good news is that most screencasts don’t need high quality recording equipment. There are dynamic and diaphragm microphones to choose from; in my opinion, it is usually better to buy a diaphragm microphone, although it picks up more ambient noise. Dynamic microphones are less sensitive to accidental “pops” or other unwanted noise, but sound less clear and clean.

Wrong tools doesn’t necessarily mean that you are using wrong coding or designing applications, it also can mean a wrong environment or computer setup. On the photo above, the setup looks solid and well-organized. Image credit.

Wrong tools doesn’t necessarily mean that you are using wrong coding or designing applications, it also can mean a wrong environment or computer setup. On the photo above, the setup looks solid and well-organized. Image credit.

I ended up buying a USB microphone that has an amplifier built-in, so it doesn’t need any other special equipment; dynamic microphones usually need a separate amplifier. I know some screencasters who buy “stand” microphones, which they attach to a freely movable arm that is attached to the wall. That way, they can move their microphone around and always have a good position to their microphone.

Placing a microphone is quite easy. I would recommend not putting the microphone directly in front of you, as some vowels (like “p” or “t”) can “pop” the microphone, resulting in a distorted recording. Most recording microphones have a cardioid polar pattern that records well when sound comes from the front, but is less sensitive to sound from the side and the back. As humans, we are orbital emitters which means that for us, speaking into a microphone placed to the side of our mouths sounds equally good as speaking directly into it. The only difference is that the “p” and “t” sounds don’t influence the diaphragms’ movement, because all of the sonic energy doesn’t go in the microphone’s direction. [3]

Some screencasters, like me, prefer headset microphones as they are always the right distance to the mouth. A possible downside of professional diaphragm headset microphones, however, might be the need for a separate audio interface. Fortunately, mine wasn’t that expensive; I’m using a MiPRO MU-55HN.

I can’t recommend buying microphones that just “look good,” such as those blue-light emitting microphones. Low price usually means low quality. I suggest going into a professional music shop to ask for help, as they have enough experience to sell you the right microphone — perhaps an even cheaper and better one — than the amateur shops would.

Recording Studio

How do you choose an appropriate recording studio? Some people record their screencasts in their offices, which have bare walls; this makes the recording sound equally “bare,” like you have recorded in a washroom. There’s nothing you can do about that, except by putting more stuff on the walls and desks. Placing “reflecting material” helps the sonic waves spread across the room, resulting in better audio quality. The recorded voice will always sound like the room it has been recorded in. If it shouldn’t sound like your office, don’t record there! It’s simple as that! Spend one or two hours in a different venue getting your audio recording right, and then move back into your office for editing. It’s really worth it!

Summary

This article gives you a brief overview of some of the most common mistakes screencasting beginners make. I have great hopes now of seeing fewer screencasts recorded with a mobile phone! I tried to explain how to use zoom and pan more effectively and how to emphasize different portions of a screencast; we discussed that click effects, or keyboard-shortcut-overlays, should only be used wherever helpful, not wherever possible. Some of you may have decided to acquire additional or new gear for your recording equipment collection. And of course, choosing the right place to record your audio is the final icing on your screencasting cake.

Footnotes

- I’m using the word “application” here as an example, but it can apply to everything. (jump back to the article)

- Zoom may be called “scale” depending on the software in use. Professional video editing suites tend to use the word scale rather than zoom, whereas screencast-specific programs use the word zoom instead of scale. (jump back to the article)

- This is because high frequency sounds are emitted more directly from our mouths. (jump back to the article)

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st