Following A Web Design Process

Almost every Web designer can attest that much of their work is repetitive. We find ourselves completing the same tasks, even if slightly modified, over and over for every Web project. Following a detailed website design and development process can speed up your work and help your client understand your role in the project. This article tries to show how developing a process for Web design can organize a developer’s thoughts, speed up a project’s timeline and prepare a freelance business for growth.

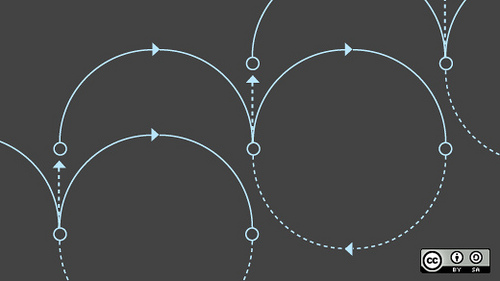

First of all, what exactly is a ‘process’? A Web development process is a documented outline of the steps needed to be taken from start to finish in order to complete a typical Web design project. It divides and categorizes the work and then breaks these high-level sections into tasks and resources that can be used as a road map for each project.

A Typical Process

Here is a standard process that was put together using examples from around the Web as well as my own experience. (Note: Please see the resource links at the end of each phase.)

1. Planning

The planning stage is arguably the most important, because what’s decided and mapped here sets the stage for the entire project. This is also the stage that requires client interaction and the accompanying attention to detail.

- Requirements analysis. This includes client goals, target audience, detailed feature requests and as much relevant information as you can possibly gather. Even if the client has carefully planned his or her website, don’t be afraid to offer useful suggestions from your experience.

- Project charter. The project charter (or equivalent document) sums up the information that has been gathered and agreed upon in the previous point. These documents are typically concise and not overly technical, and they serve as a reference throughout the project.

- Site map. A site map guides end users who are lost in the structure or need to find a piece of information quickly. Rather than simply listing pages, including links and a hierarchy of page organization is good practice.

- Contracts that define roles, copyright and financial points. This is a crucial element of the documentation and should include payment terms, project closure clauses, termination clauses, copyright ownership and timelines. Be careful to cover yourself with this document, but be concise and efficient.

- Gain access to servers and build folder structure. Typical information to obtain and validate includes FTP host, username and password; control panel log-in information; database configuration; and any languages or frameworks currently installed.

- Determine required software and resources (stock photography, fonts, etc.). Beyond determining any third-party media needs, identify where you may need to hire sub-contractors and any additional software you may personally require. Add all of these to the project’s budget, charging the client where necessary.

Resource links for this phase:

- Jumpchart: Client/developer collaboration tool

- Dropbox: File-sharing and collaboration tool

- Mindmeister: Free online mind-mapping software

- Writing Bulletproof Web Design Contracts

2. Design

The design stage typically involves moving the information outlined in the planning stage further into reality. The main deliverables are a documented site structure and, more importantly, a visual representation. Upon completion of the design phase, the website should more or less have taken shape, but for the absence of the content and special features.

- Wireframe and design elements planning. This is where the visual layout of the website begins to take shape. Using information gathered from the client in the planning phase, begin designing the layout using a wireframe. Pencil and paper are surprisingly helpful during this phase, although many tools are online to aid as well.

- Mock-ups based on requirements analysis. Designing mock-ups in Photoshop allows for relatively easy modification, it keeps the design elements organized in layers, and it primes you for slicing and coding when the time later on.

- Review and approval cycle. A cycle of reviewing, tweaking and approving the mock-ups often takes place until (ideally) both client and contractor are satisfied with the design. This is the easiest time to make changes, not after the design has been coded.

- Slice and code valid XHTML/CSS It’s coding time. Slice the final Photoshop mock-up, and write the HTML and CSS code for the basic design. Interactive elements and jQuery come later: for now, just get the visuals together on screen, and be sure to validate all of the code before moving on.

Resource links for this phase:

- Printable Sketch Templates for Wireframing

- Color Scheme Designer

- Type Tester, font comparison

- iPlotz, online template and wireframing tool

- Stripe Generator

- Favicon Generator

- Icon Finder

- Stock Exchange, free stock photos

3. Development

Development involves the bulk of the programming work, as well as loading content (whether by your team or the client’s). Keep code organized and commented, and refer constantly to the planning details as the full website takes shape. Take a strategic approach, and avoid future hassles by constantly testing as you go.

- Build development framework. This is when unique requirements might force you to diverge from the process. If you’re using Ruby on Rails, an ASP/PHP framework or a content management system, now is the time to implement it and get the basic engine up and running. Doing this early ensures that the server can handle the installation and set-up smoothly.

- Code templates for each page type. A website usually has several pages (e.g. home, general content, blog post, form) that can be based on templates. Creating your own templates for this purpose is good practice.

- Develop and test special features and interactivity. Here’s where the fancy elements come into play. I like to take care of this before adding the static content because the website now provides a relatively clean and uncluttered workspace. Some developers like to get forms and validation up and running at this stage as well.

- Fill with content. Time for the boring part: loading all of the content provided by the client or writer. Although mundane, don’t misstep here, because even the simplest of pages demand tight typography and careful attention to detail.

- Test and verify links and functionality. This is a good time for a full website review. Using your file manager as a guide, walk through every single page you’ve created—everything from the home page to the submission confirmation page—and make sure everything is in working order and that you haven’t missed anything visually or functionally.

Resource links for this phase:

- Wufoo, form generator

- Adobe Browserlab, cross-browser analysis

- Choosing the Right Web Platform

4. Launch

The purpose of the launch phase is to prepare the website for public viewing. This requires final polishing of design elements, deep testing of interactivity and features and, most of all, a consideration of the user experience. An important early step in this phase is to move the website, if need be, to its permanent Web server. Testing in the production environment is important because different servers can have different features and unexpected behavior (e.g. different database host addresses).

- Polishing. Particularly if you’re not scrambling to meet the deadline, polishing a basically completed design can make a big difference. Here, you can identify parts of the website that could be improved in small ways. After all, you want to be as proud of this website as the client is.

- Transfer to live server. This could mean transferring to a live Web server (although hopefully you’ve been testing in the production environment), “unhiding” the website or removing the “Under construction” page. Your last-minute review of the live website happens now. Be sure the client knows about this stage, and be sensitive to timing if the website is already popular.

- Testing. Run the website through the final diagnostics using the available tools: code validators, broken-link checkers, website health checks, spell-checker and the like. You want to find any mistakes yourself rather than hearing complaints from the client or an end-user.

- Final cross-browser check (IE, Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Opera, iPhone, BlackBerry). Don’t forget to check the website in multiple browsers one last time. Just because code is valid, doesn’t mean it will sparkle with a crisp layout in IE 6.

Resource links for this phase:

- W3C Validation (HTML, CSS)

- Adobe Browserlab, cross-browser analysis

5. Post-Launch

Business re-enters the picture at this point as you take care of all the little tasks related to closing the project. Packaging source files, providing instructions for use and any required training occurs at this time. Always leave the client as succinctly informed as possible, and try to predict any questions they may have. Don’t leave the project with a closed door; communicate that you’re available for future maintenance and are committed to ongoing support. If maintenance charges haven’t already been shared, establish them now.

- Hand off to client. Be sure the client is satisfied with the product and that all contractual obligations have been met (refer to the project charter). A closed project should leave both you and the client satisfied, with no burned bridges.

- Provide documentation and source files. Provide documentation for the website, such as a soft-copy site map and details on the framework and languages used. This will prevent any surprises for the client later on, and it will also be useful should they ever work with another Web developer.

- Project close, final documentation. Get the client to sign off on the last checks, provide your contact information for support, and officially close the project. Maintain a relationship with the client, though; checking in a month down the road to make sure everything is going smoothly is often appreciated.

As stated, this is merely a sample process. Your version will be modified according to your client base and style of designing. Processes can also differ based on the nature of the product; for example, e-commerce websites, Web applications and digital marketing all have unique requirements.

Documenting The Process

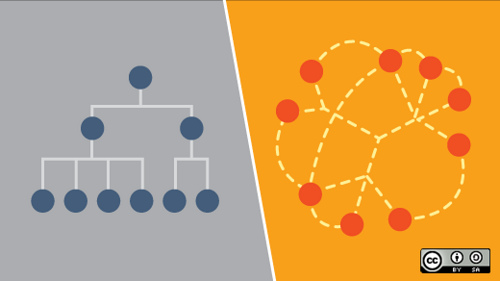

Create and retain two versions of your Web design process: One for you or your team to use as a guide as you work on the back end, and one to share with clients. The differences between the two should be intrinsically clear: yours would be much more detailed and contain technical resources to help with development; the client’s would be a concise, non-technical map of the process from start to finish.

Common tools for documenting the business process are a simple Microsoft Word document, Microsoft Visio and mind-mapping software such as Freemind. If you’re ambitious, you could even develop your own internal Web-based tool.

Using The Process

By now, you should understand what a process looks like, including the details of each phase, and have some idea of how to construct your particular Web design process. This is a great first step, but it’s still only a first step! Don’t miss this next bit: knowing how a process can enhance your overall business and how to use it when approaching and interacting with clients.

Refining The Process

The process will be different for each designer, and for each project. Develop a process for yourself, and identify whatever is useful to you or your team. Only then will the process be truly useful. After all, freelancers can serve drastically different target markets.

Bulleted lists are well and good, but the process can be much more useful and elaborate than that. Many of the resources, tools and links posted on Web design blogs and Twitter feeds fit into different parts of the process. An incredibly useful way to refine the process is to add resource links to each phase, and to develop your own resources, such as branded document templates.

Some commonly used documents of freelancers:

- Invoice,

- Project charter,

- Documentation for hand-off to client,

- User accounts,

- Database table charts,

- Site map.

Files And Archive

Documentation and storage are important to grasp. As mundane as these tasks can be, they certainly help when tax season rolls around or when a small freelance venture begins to expand. You can never be too disciplined when it comes to efficiency in work and time. You could establish a standard document format and folder structure for all of your clients, or maintain a list or archive of previous clients and project files. You could employ anything from simple lists to all-out small-business accounting practices.

A Process Puts The Client At Ease

Many clients view Web development as a black box, even after you’ve tried to educate them on its methods. To them, they provide their requirements, suggestions and content, and then some time later a website appears or begins to take shape. They’re often completely unaware of major aspects of the process, such as the separation of design and development. Having an organized and concise process on hand can help organize a client’s thoughts and put their mind at ease, not to mention help them understand where their money is going.

Outlining my basic process as a freelancer is by far the most common first step I take with potential or new clients. A quick, high-level “This is how it works” discussion provides a framework for the entire project. Once you have this discussion, the client will better understands what specifically is needed from them, what you will be delivering at certain points in the timeline and what type of work you’ll be engaging in as you go along. Most of all, the discussion can nip any miscommunication or confusion in the bud.

Designers are often too deep into Web design to realize that most people have no idea what they do or understand their terminology or know the steps involved in creating a finished product. Starting fresh with a understandably “clueless” client can be daunting.

It’s A Business

It’s a business, and the steps outlined here are basically the path to small-business management. As you grow in clients or staff or contractors, you’ll find yourself with an ever-growing to-do list and a headache from all of the things to keep track of. Give yourself a break, and invest some time in finding tools to help you get the job done efficiently. An expanded process document is a great first step on this path.

Tips

- Ask a non-technical friend to review your process. If it makes sense to them, it will make sense to your client.

- Use the processes of other designers as a starting point to build or refine your own. See the related resources links.

- Build document templates and Web apps into your process. This will save time and make you more professional.

Risks

One process cannot be applied to every project. Although your process will be useful when you first engage a client in the planning discussion, be sure to review it before the discussion takes place to ensure it fits the project.

Further Resources

Here are some links to resources that showcase sample Web design processes, as well as tools and templates to build integrate in your own process.

- 6 Phases of the Website Design/Development Process A great example of a Web design process broken into six steps.

- Comparison of Web Design Workflow Processes A detailed comparison of different types of processes.

- 50 Essential Web Apps for Freelancers A great collection of Web applications to build into your process.

- 3 Links to Websites Offering Free Document Templates A great place to gather document templates for freelance business use.

Have further resources to share? Post them in the comments.

Further Reading

You may also want to take a look at the following related posts:

- How To Be A Samurai Designer

- Effective Strategy To Estimate Time For Your Design Projects

- Useful Business Advice And Tips For Web Designers

- Web Design Tips for Beginners – Everything I Wish I Knew When I Started

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st