Stop Writing Project Proposals

After several grueling days I had finally finished the proposal. I sent it off and waited for a response. Nothing. After a few weeks, I discovered that they were “just looking”. Despite the urgency and aggressive timeline for the RFP (Request For Proposal) plus the fact that we had done business with this organization before, the project was a no-go. My days of effort were wasted. Not entirely, though, because the pain of that loss was enough to drive me to decide that it wouldn’t happen again.

I work at a Web development company and we’ve experimented with proposal writing a lot over the years. We’ve seen the good and the bad, and we have found something better. In this article I will share the pains that we have experienced in the proposal writing process, the solution we adopted, and our process for carrying out that solution. I’ll also give you guidelines to help you know when this solution is and isn’t appropriate.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Effectively Planning UX Design Projects

- Web Design Questionnaires, Project Sheets and Work Sheets

- How To Convince The Client That Your Design Is Perfect

- Meeting Your Client for the First Time

Project Proposal Writing Causes Pain

After several years of writing proposals, we began to notice that something wasn’t right. As we considered the problem we noticed varying levels of pain associated with the proposal writing process. We categorized those pains as follows:

- The Rush. Getting a proposal done was usually about speed. We were racing against the clock and working hard to deliver the proposal as efficiently and as effectively as possible. However, sometimes corners would get cut. We’d reuse bits and pieces from older proposals, checking and double-checking for any references to the previous project. While the adrenaline helped, the rush gets old because you know that, deep down, it’s not your best work. Besides, you don’t even know if you’re going to close the deal, which leads to the next pain.

- The Risk. Our proposal close ratio with clients that came directly to us was high. We’d work hard on the proposals and more often than not, we’d close the deal. The risk was still there, however, and I can think of several proposals that we had spent a lot of time and effort on for a deal that we didn’t get. Not getting the deal isn’t the problem — the problem is going in and investing time and energy in a thorough proposal without knowing if there is even the likelihood that you’re going to close the deal.

- The Details. The difference between a project’s success and its failure is in the details. In proposal writing, the details are in the scope. What work is included, what is not, and how tight is the scope? Now, this is where the “rush” and the “risk” play their part. The rush typically causes us to spend less time on details and the “risk” says: “Why spell it all out and do the diligence when you might not even get the project?” A self-fulfilling prophecy, perhaps, but a legitimate concern nonetheless. Selling a project without making the details clear is asking for scope creep, and turns what started out as a great project into a learning experience that can last for years.

Now, writing is an important part of the project and I’m not about to say you shouldn’t write. Having a written document ensures that all parties involved are on the same page and completely clear on exactly what will be delivered and how it will be delivered. What I’m saying, though, is that you should stop writing proposals.

Write Evaluations, Not Proposals — And Charge For Them

A few years back, we decided to try something new. A potential client approached us and rather than preparing another project proposal, we offered the client what we now call a “Project Evaluation.” We charged them a fixed price for which we promised to evaluate the project, in all of our areas of expertise, and give them our recommendations.

They agreed, paid the price, and we set out to deliver. We put a lot of effort into that evaluation. We were in new territory and we wanted to make sure that we delivered it well. So we finished the report and sent it to them. The client liked it, agreed with our recommendations, and started a contract with us to do the work.

That project became a game changer for us, starting an on-going relationship that opened doors into a new market. It was the process of the evaluation itself that brought the new market potential to our attention, and gave us the opportunity to develop this business model. It was a definite win, and one that a project proposal couldn’t have delivered.

What Is A Project Evaluation?

A “Project Evaluation”, as we’ve defined it, is a detailed plan for the work that is to be done on a project, and explains how we do it. We eliminate the guess work, and detail the project out at such a level that the document becomes a living part of the development process, being referred back to and acting as the guide towards the project’s successful completion.

The Benefits Of (Paid) Project Evaluations

As we put our proposal writing past behind us and embraced the evaluation process, we noticed a strong number of benefits. The most prominent of those benefits are the following.

Qualification

If a client is unwilling or unable to pay for a project evaluation, it can be an indicator that the project isn’t a match. Now, we may not always charge for evaluations (more on that later). We also recognize a deep responsibility on our part to make sure that we have intelligently and carefully explained the process and value of the evaluation. After all that is done, though, you may run into potential clients who just don’t want to pay what you’re charging, and it’s better to find this out right away then after writing a long proposal.

Attention to Details

Having the time available to do the research and carefully prepare the recommendations means that we are able to eliminate surprises. While the end result may be a rather large document, the details are well organized and thorough. Those details are valuable to both the client (in making sure they know exactly what they’re getting) and to the development team (in making sure that they know exactly what they’re delivering).

No Pricing Surprises

Figuring out all the details and ironing out a complete scope means that we’re able to give a fixed price, without surprises. This gives the client the assurance up front that the price we gave them is the price they’ll pay. In more than a few cases, the time we’ve spent working out the details has eliminated areas of concern and kept our margins focused on profit, not on covering us “just in case.”

Testing the Waters

When a potential client says “Yes” to an evaluation, they are making a relatively small commitment — a first step, if you will. Rather than a proposal that prompts them for the down payment to get started on the complete project, the evaluation process gives us time and opportunity to establish a working relationship. In most cases, the process involves a lot of communication which helps the client learn more about how we work, as we learn more about how they work. All this is able to take place without the pressure of a high-budget development project. And by the end of the evaluation, a relationship is formed that plays a major factor in the decision process to move forward.

Freedom to Dream

Occasionally, we spend more time on an evaluation than we had initially expected. But knowing how our time is valued has given us the freedom to explore options and make recommendations that we might not have made otherwise. In our experience, the extra time and energy that the context of a paid evaluation provides for a project has consistently brought added value to the project, and contributed to its ultimate success.

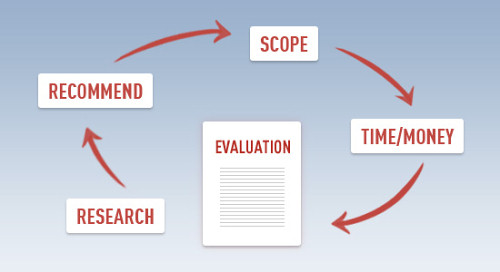

The Evaluation Writing Process

Over the years we have refined (and continue to refine) a process that works well for us. As you consider the process, look for the principles behind each step, and if you decide to bring this into your business, look for ways to adapt this process and make it your own.

#1 — Do the Research

The heart of the evaluation process is the research. If it’s a website redesign project, we read through each and every page on the website. We take notes and thoroughly absorb as much content as possible. Our objective is to get to the heart of the project and gain as much of the organization’s perspective as possible.

If it’s a custom programming project, we try to get inside the project’s concept, challenge it, look for flaws in the logic, research relevant technologies, and work to make recommendations that keep the goals of the project in mind.

We spend time with the client by phone, over Skype, via email, and sometimes even in person. As our research uncovers problems or finds solutions, we run them by the client and gather their feedback.

The research process allows us to go deep, and in our experience it has always paid off, giving us a thorough grasp of the project and providing a foundation to make intelligent, expertise-driven recommendations.

#2 — Offer Recommendations

Each project evaluation is different. Depending on the nature of the project we may make recommendations regarding technology, content organization, marketing strategies, or even business processes. The types of recommendations we make have varied greatly from project to project, and are always driven by the context and goals of the project.

When it comes to areas of uncertainty for the client, we work hard to achieve a balance between an absolute recommendation and other options. If the answer is clear to us, we’ll say so and make a single, authoritative recommendation. However, when an answer is less clear, we give the client options to consider (along with our thoughts) on why or why not an option might be a match.

We share our recommendations with the client throughout the evaluation process, and when the final report is given, there are rarely any surprises.

#3 — Prepare the Scope

After we’ve worked through our recommendations, we put together a technical scope. This is typically the longest part of the document. In the case of a Web design project, we go through each page of the website, explaining details for the corresponding elements of that page. The level of detail will vary based on the importance of a particular page.

The scope document is detailed in such a way that the client could take it in-house, or even to another developer, and be able to implement our recommendations.

As the project commences, the scope document will often be referred to, and can function as a checklist for how the project is progressing.

#4 — Prepare the Timeline & Estimate

With the scope complete, calculating the cost and preparing an estimate becomes a relatively straightforward process. While how one calculates the price may vary, all the information is now available to see the project through from start to finish, identifying the challenges, and determining the amount of resources required to meet the project’s objectives.

Note: Prior to the start of the evaluation process, we nearly always give the potential client a “ball park” estimate. So far, that estimate typically ends up being about ten times the cost of the evaluation.

We take the estimating process very seriously, both in the ball park stage and especially here within the context of an evaluation. Once we set a price down we don’t leave room for “oops!” and “gotchas!”, and that means we are extra careful to calculate as accurately as possible, both for our sake and for the sake of the client.

Now, because of the nature of the evaluation, we are often able to research and explore options above and beyond what the client originally brought to our attention. In the case of a Web application, this might be an added feature or a further enhancement added onto a requested feature. Within the scope of the evaluation we carefully research these extras, and when appropriate, present them as optional “add-ons” within the timeline and estimate.

They are truly optional, and while always recommended by us, we leave the decision up to the client (there’s no use wasting research energy on an add-on you wouldn’t fully recommend). In cases where the budget allows for them, they are nearly always accepted. In cases where a tighter budget is involved, the add-ons are typically set aside for future consideration.

When Evaluations Are Appropriate

A project evaluation functions like the blueprints for a new office building. Imagine that I own a successful construction company, and I have a number of world-class office construction projects to my credit. A new client comes to me after seeing some of my work and tells me “I want a building just like that!”. Assuming, of course, that I own the rights to the building, I can say “Sure!” and tell them how much it will cost. Why? The blueprints have already been drawn.

Now, there will be variable factors, such as where they choose to have the building built, and any customizations they may request matter. But in most cases no new blueprints will be needed, and I can proceed with construction without charging them for the plans.

Suppose another client comes to me after seeing one of my buildings and asks me to build an entirely new design for them. A new design calls for new blueprints all of their own, and these must be developed before the project begins. Can you imagine a large-scale construction project without any blueprints?

Web development is the same way. In our experience, evaluations are appropriate when a client comes to us and asks us to take on a project outside of our existing set of “blueprints”. Examples where we’ve found a project evaluation necessary include:

- A redesign of an existing website.

- Developing a new Web application.

- Bringing new technology into an existing project.

Without an evaluation you’re either left to go ahead and do the research on your own (with the weight of the rush, and the risk on your shoulders) or you’re stuck making as educated a guess as possible for the scope of the project. This dangerous guessing in a situation where an evaluation is appropriate can leave you with an estimate that is too high (which can mean losing the project) or even worse, an estimate that is too low.

When Evaluations Are Not Appropriate

When a project is familiar, and doesn’t require an evaluation (or fits within the scope of an existing type of evaluation), we give an informal, direct estimate along with a scope of the work. Small to mid-sized Web design projects typically fall into this category. While the content and design are new, the process isn’t. The key here is the experience and confidence in your abilities (and the abilities of your team) that the work will get done within budget to the expected delight of all parties involved.

Conclusion

Project evaluations up until now haven’t been given much attention. I would suggest it is a simple concept that has been overlooked and passed by amidst the rush of a booming Web development industry. I invite you to implement the process, experience the benefits, and stop the pain of proposal writing.

I thank you, dear reader, for your time in considering this concept. And I thank you in advance for your feedback.

(jvb) (il)

Register!

Register!

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st