Inside Microsoft’s New Rendering Engine For The “Project Spartan”

Editor’s Note: Last week, Microsoft made its biggest announcement for the web since it first introduced Internet Explorer in 1995: a new browser, codenamed “Project Spartan.” So, what does this mean for us as designers and developers? What rendering engine will Spartan be using, and how will it affect our work? We spoke with Jacob Rossi, the senior engineer at Microsoft’s web platform team, about the new browser, the rendering engine behind it, and whether it’s going to replace Internet Explorer in the long run. This article, written by Jacob, is the result of our conversations, with a few insights that you may find quite useful.

Spartan is a project that has been in the making for some time now and over the next few months we’ll continue to learn more about the new browser, what it has to offer users, and what its platform will look like. It will be a matter of few months until users and developers alike will be able to try Spartan for themselves, but we can share some of the interesting bits already today. This article will cover the inside story of the rendering engine powering Spartan, how it came to be, and how 20 years of the Internet Explorer platform (Trident) has helped inform how our team designed it.

Recommended reading: But The Client Wants IE 6 Support!

Lessons Learned From Internet Explorer

Twenty years ago, Microsoft first introduced Internet Explorer to the world. For many users, it’s a household name and a brand recognized across the globe, but for web developers, those quirky older versions of Internet Explorer often make it difficult to recognize Microsoft’s recent efforts in supporting and implementing web standards. Though Internet Explorer’s legacy versions are likely to be remembered by web developers for bugs, hacks and dirty workarounds, IE did shape the web in a positive way for web developers by bringing CSS, dynamic HTML scripting and the DOM, AJAX/XMLHttpRequest, drag drop, innerHTML, hardware acceleration, and other technologies to the web.

On the browser team at Microsoft, we consider ourselves a learning organization. Each year, we take the time to reflect on our achievements and our failures to learn and grow. From that, each release of IE has made a lasting impact on how we engineer. Our learnings about the importance of cooperation amongst browser vendors, standards, compatibility, interoperability, performance, and security all come together to shape how we designed our new rendering engine.

Recommended reading: What’s The Deal With The Samsung Internet Browser?

Microsoft’s New Rendering Engine

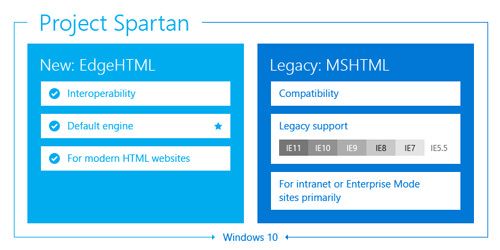

The new Microsoft browser is going to be powered by a new rendering engine, EdgeHTML.dll. Windows 10 already has it integrated, and it will be separate from Trident (MSHTML.dll) that powered Internet Explorer for decades.

As we know, the latest versions of Trident powering Internet Explorer 11, did show a remarkable support for standards (I started to make a list of some of the notable ones, but stopped after I hit 75 specs). But its progress was heavily weighed down by the burden of legacy support for IE5.5, IE7, IE8, IE9, and IE10 document modes — a concept the web no longer needs.

So we set about to create a new engine using IE11’s standards support as a baseline. I watched Justin Rogers, one of our engineers, press “Enter” on the commit that forked the engine—it took almost 45 minutes just to process it (just committing the changes, not building!). When it completed, there was a liberating silence when we realized what this now enabled us to do: delete code, every developer’s favorite catharsis.

In the coming months, swathes of IE legacy were deleted from the new engine. Gone were document modes. Removed was the subsystem responsible for emulating IE8 layout quirks. VBScript eliminated. Remnants like attachEvent, X-UA-Compatible, currentStyle were all purged from the new engine. The codebase looks little like Trident anymore (far more diverged already than even Blink is from WebKit).

Project Spartan will be powered by a new rendering engine and the Chakra JavaScript engine, introduced with IE 9.

What remained was a clean slate. A modern web platform built with interoperability and standards at its core. From there, we began a major investment in interoperability with other modern browsers to ensure that developers don’t have to deal with cross-browser inconsistencies. To date, we’ve fixed over 3000 interoperability issues (some dating back to code written in the 90’s) on top of the over 40 new web standards we’re working on. For example, longstanding innerHTML issues are now fixed. Even recent standards, like Flexbox, are getting renewed love so that the new engine matches the latest spec (this will show up in a future Windows 10 preview build). Project Spartan will also have an updated version of the F12 developer tools. A few of my personal favorites that are in the preview builds or on their way:

- Preserve-3d

- The most advanced support for ES6 at the moment

- XPath

- Web Audio

- Media Capture API

- Web RTC 1.1 (ORTC)

- Touch Events

- Content Security Policy

- HTTP/2

As it turns out, a modern and interoperable rendering engine alone isn’t enough to magically make the web just work. To do that, the browser also has to make sure that sites provide the browser with the up-to-date, “modern browsers” code. So our new engine also comes with a new user agent string. If user agent string tokens were stickers, then the new engine’s UA String looks like the backs of most web devs laptops these days. But this yields surprisingly positive results in compatibility and enables lots of sites to send our new engine modern content. It also gives me one more opportunity to beat the drum again: user agent sniffing should be avoided at all costs!

“That’s Great, But My Company Has Sites That Require IE8.”

In order to ensure that we also retain backwards compatibility, we will not be getting rid of Trident. Instead, we designed and implemented a dual-engine approach, where either the new modern rendering engine or Trident can be loaded. This switch happens transparently to the user. Windows 10 will use EdgeHTML for the web (so no more worrying about doc modes) and only load Trident for legacy enterprise sites. This dual-engine approach enables businesses to update to a modern engine for the web while running their mission critical applications designed for IE of old, all within the same browser. Even better, with the dual-engine approach we can ensure that only essential security fixes are made to Trident, minimizing code churn and ensuring that compatibility is preserved for enterprise sites, while we focus on innovating in the new (and always up to date) rendering engine untethered.

Spartan is the browser we expect people will be using on Windows 10. That said, there are a set of businesses that have built key tools on top of Internet Explorer’s legacy extensibility model (e.g. custom ActiveX, toolbars, browser helper objects, etc.). So, Internet Explorer will be made available on Windows 10 for some enterprise web applications that require a higher degree of backward compatibility. This version of Internet Explorer will use the same dual-engine approach as Spartan with EdgeHTML the default for the web, meaning developers won’t need to treat Internet Explorer and Spartan differently and our standards roadmap will be the same. The browser will be powered by the Chakra JavaScript engine.

“That’s Great, But Some Of My Users Still Have IE8.”

We hear you. What’s painful for web devs to support is also painful for our browser team. Back in May, we talked about getting our users upgraded as a top priority. Later in August, we announced a browser support policy that will encourage users to get up to date. Most significantly, we announced last week that Windows 10 will be a free upgrade to customers running Windows 7, Windows 8.1, and Windows Phone 8.1 who upgrade in the first year after launch. Furthermore, we’ll treat Windows 10 as a service—keeping users up to date and delivering features when they are ready (“auto-update”), not waiting for the next major release. This means the new rendering engine will always be truly evergreen.

The Roadmap Ahead

Another welcomed change that we’ve been rolling out over the past year is a promise for increased openness about our web platform plans and roadmap. Over the last year, you’ve hopefully experienced some of this through our open standards roadmap (one of my personal side projects), our Reddit AMA, regular dialog through @IEDevChat, and sharing preview builds very early in our development process. You’ll see more of this over the next year.

For standards support, we will maintain a pipeline of new features we’re working on. What’s ahead in the near future are Web Audio, Image srcset, @supports, Flexbox updates, Touch Events, ES6 generators, and others that have all seen commits in the recent weeks. What lies beyond are big ticket items like Web RTC 1.1 (ORTC) and Media Capture (getUserMedia() for webcam/mic access). Beyond that, we’re starting to use your input (and other factors, such as real world usage data gathered through the Bing crawler, which now can run our new engine) to shape how we prioritize our next platform investments.

Our plans for the platform in the initial release aren’t fixed—developer feedback has and will continue to shape it. So please expect agile changes. Here’s what you can do to get ahead:

- Test out the new engine. EdgeHTML can be enabled today within Internet Explorer in the Windows 10 Technical Preview (a preview of Project Spartan will come later) by navigating to

about:flagsand enabling “Experimental Web Platform Features.” If you’re on a Mac or don’t have a machine you can upgrade to Windows 10 preview builds yet, there’s the recently launched RemoteIE cloud service that lets you stream a version of IE running the new engine without downloading large virtual machine images (note: we’re still in the process of rolling out the last week’s preview build to RemoteIE). - File bugs. Our investment in interoperability with modern browsers is fueled by data from bug reports and real world site impact.

- Feel free to monitor and give us feedback on our standards roadmap – based on developer feedback over 40 different standards have gone from “under consideration” to in development since we launched our open roadmap back in May 2014.

Personally, I’m excited to share this inside scoop on the new web rendering engine powering Project Spartan in Windows 10 so early in our development process. We look forward to sharing more of our plans and in the coming months. In the meantime, if you have feedback, reach out to me and the rest of our team. Let’s make the web work for you.

Further Reading

- Advanced Form Control Styling With Selectmenu And Anchoring API

- Getting Started With Neon Branching

- Useful DevTools Tips and Tricks

- I Used The Web For A Day On Internet Explorer 8

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st Register!

Register!