How Copywriting Can Benefit From User Research

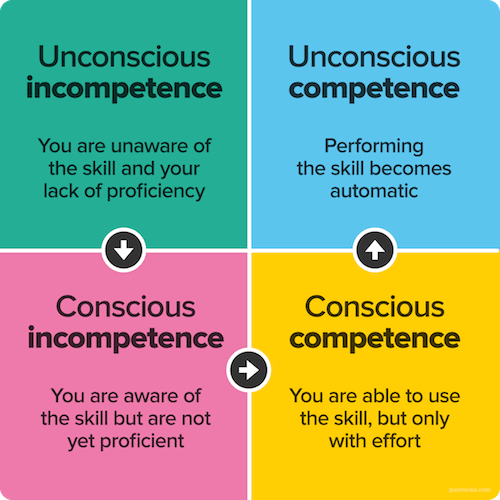

I’ve often heard there are four stages along the road to competence: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and unconscious competence. Most of us begin our careers “unconsciously incompetent,” or unaware of how much we don’t know.

I’ll never forget the first time I moved from unconscious to conscious incompetence. I was working as an office manager at a small software company, and having been impressed by my writing skills, the director of sales and marketing asked me to throw together a press release, welcoming the new CEO.

At the age of 23 I was a more than competent writer. I had roughly 18 years of experience making up (and writing down) stories, poems, book reports, fan fiction, pen pal letters, composition papers, reaction essays, and science lab reports. Yet I had no earthly clue how to begin to write a press release.

I read through a few of the company’s earlier press releases, and still the words refused to come together. What had me stumped was my complete inability to imagine who would read this press release. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I was suffering a common copywriting problem: a lack of user knowledge.

In this article, we’ll review ways to give copywriters the knowledge they need via user research. Specifically, we’ll look at which types of user research are most valuable to copywriters, and how they can get involved.

Content Strategy Is Not Copywriting

Copywriters write copy. They write text, microcopy, blurbs and articles. Content strategists, on the other hand, plan for the creation, curation and management of content, including — yes — copy, as well as video and images.

As a content strategist, I now do a lot of user research. Clients expect me to learn who is using their website or application. I create personas that show how those users spend their days, what keeps them up at night, what they think about, who they spend their time with, how they spend their time online, what they purchase, and why they interact with the client’s product.

Every project I work on involves some measure of user research, whether I work on my own or with an official research team. Sometimes I observe users as they use products. Other times I set up tree tests to see how users react to my terminology and nomenclature. When it’s all over, I work with the client to establish a message they want to communicate. I compile the final information into a report or guidelines to serve as a reminder of that message, and we go through the new screens or pages and decide how to communicate the message.

Eventually, my personas, research reports and guidelines are passed on to copywriters. But many copywriters aren’t working with content strategists and therefore don’t have access to that information. More to the point, I don’t create those reports or guidelines with the copywriter in mind. And yet, the copywriter is the person who is having a conversation with the user. Shouldn’t the copywriter have direct access to information about the user they are conversing with? Moreover, shouldn’t the copywriter have opportunities to hear how the user speaks, the sorts of questions they ask, and the vocabulary they use?

(The answer is yes.)

User Research: The Big Picture

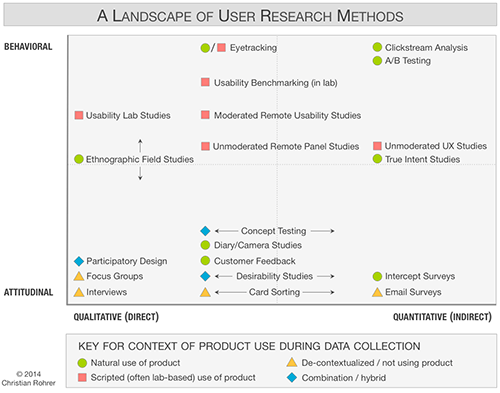

User research is a key stage in the UX design process, and it takes many forms. Christopher Rohrer, writing for the Nielsen Norman Group, explains user research styles as encompassing some combination of four elements:

- Behavioral research, which observes what people do.

- Attitudinal research, which observes what people say.

- Qualitative research, which analyzes why people do things, and how to improve those things.

- Quantitative research, which analyzes data relating to measurable elements, such as how many prospects convert to customers, or how much of a product a company sells.

From user research we get reports with detailed information on users — the people we are creating a website or a product for. Designers, content strategists and developers employ user research results to improve their designs, their guidelines and prototypes.

Types Of User Research For Copywriters

User research is a great tool for copywriters because it can help them to better understand how users speak, and what they want or need. Let’s review some popular forms of research, and look at how they might influence content creation and benefit copywriters.

Ethnographic Field Studies

What makes an ethnographic field study unique is that it takes place in the user’s home or office. The goal is to see users in their natural environments, as though the researcher was going on safari, hoping for a glimpse of customers in the wild. For a UX designer or a content strategist, ethnographic field studies provide valuable context to understand users’ distractions, as well as their daily influences and familiar interfaces.

For a copywriter, this sort of study is also an opportunity to see what users read, where they go online and what vocabulary they are encountering. For example, a copywriter might interview a lawyer and listen for legal terminology the lawyer uses in daily conversation, and when talking about how they spends their day. The copywriter would then be able to use that same vocabulary in the headings of a website designed for lawyers. Such studies are particularly useful for:

- Brand redesigns where stakeholders are asking for a (nondescript) “friendlier tone.”

- Situations where the target audience is from a dramatically different culture than the copywriter.

You can learn more about ethnography in UX.

Diary Studies

A diary study is intended for participants to share how they use the product or service without feeling self-conscious or inhibited. Because of the private nature of a diary, it’s often used for products or services that are personal, or touch on sensitive topics, such as a device to aid people suffering from a disease, or personal hygiene equipment. The diary is less intimidating than a human being, and it can also help researchers identify patterns over the course of days and weeks.

For copywriters, there is a not-so-hidden benefit to diary studies: they serve as a literal sample of how the target audience writes, which can provide tremendous insight into the type of writing they will respond to. A writer who doesn’t write with contractions may feel that a more formal style of website writing feels familiar, whereas a writer who uses little punctuation and no capitalization will feel more comfortable with a website that is more casual. Diary studies are particularly useful for:

- Audiences using a technically complex product or service, and equally technical terminology.

- Projects where the audience uses a drastically different tone of voice than the company using the process.

It’s interesting to note that for copywriters, a diary study can actually be a drawback for a product of a private or personal nature. People may feel comfortable using terms in a diary that would make them uncomfortable if seen on a public website.

You can learn more about diary studies.

Customer Feedback

It’s rare that a copywriter is given a budget to conduct their own research, but customer feedback relies on information that has already been collected. This makes it a perfect data mine for copywriters. Often an organization has a customer support department or customer retention department, collecting everything from phone calls to surveys from frustrated, angry and irate customers. But one man’s hate mail is another’s love letter, and in this case angry customer calls serve as a plethora of evidence as to how customers speak, what they say and when they say it.

As an added benefit, customer feedback tells copywriters what unanswered questions their target audience wishes they could find information on, which is incredibly helpful when choosing content priorities. For example, if the copywriter sees that several customers call asking how to get their product rebates, the copywriter will know to make that information especially easy to find on the website. However, it’s important to verify that the customers providing feedback are actually the people you’ll be writing for. If you’re writing copy for prospective users, for example, feedback from longtime customers will not provide representative information. Customer feedback is particularly useful for:

- Companies with a large volume of content to share on their sites.

- Projects where the client or team is uncertain about audience priorities.

- Projects where users are longtime customers.

- Organizations with a poor reputation, or a large contingent of unhappy clients or customers.

Learn more about getting customer feedback.

Interviews

User interviews are generally agreed to be the best possible source of user information for UX designers. It stands to reason that copywriters are just as eager to learn about users’ needs, wants, fears and preferences! The copywriter’s goal is to build up a natural, familiar conversation with perfect strangers. What better way to create a sense of camaraderie than to learn about the audience?

Although it’s unlikely that a copywriter will be given a budget with which to interview users, if the team is already conducting interviews then it’s smart for the copywriter to sit in or listen to them later. This is a situation where notes on the major takeaways will not serve as an adequate replacement. Pulling out significant clips and phrases, however, is a great way to give copywriters a taste of the interview while respecting their time limitations.

For example, on a complex project where the user researcher is already intending to report back on the interviews, they might include verbatim quotes from five of the participants for the copywriter to see. Interview are particularly useful for:

- Projects with a user research team already conducting interviews for other purposes.

- Situations where the final site needs to come across as conversational.

- Teams trying to identify what messages to communicate to their target audience.

Learn more about conducting user interviews.

Focus Groups

Many user experience teams avoid focus groups, and with good reason. Focus groups are a terrible way to learn what multiple users think. The problem with focus groups is twofold: first, people are influenced by their peers; and second, quieter or less influential voices are often overshadowed by stronger (or just plain louder!) team members. None of this concerns a copywriter.

For a copywriter, a focus group is still an excellent way to hear how multiple users speak. For example, if I had been able to meet with several people from our target audience before writing a press release, I might have asked them to help me compile a list of every possible reason press releases are valuable. Since the task is to encourage as many voices and as many answers as possible, it’s less likely that the more confident voices will be the only ones to respond. Focus groups are particularly useful for:

- Projects with very public goals (such as writing press releases or newsletters).

- Target audiences who already know one another or work well together.

Learn more about focus groups.

Participatory Design

The gap between users and designers is growing ever smaller. One method to draw them still closer together is participatory design, where users join designers for a day of brainstorming, sketching and even prototyping. Although designers ultimately take the product to the next step (in order to make final decisions that consider best practices and accessibility), participatory design helps users to be heard.

Several members of the design team often attend participatory design workshops. A copywriter should invariably be one of them. The copywriter should take notes throughout the workshop, to observe how users interact with the prototype and note the questions they ask and “must haves” they mention. For the copywriter, a participatory workshop is nearly as useful as an interview with users; people typically feel relaxed and are likely to act naturally with the product they are designing.

For example, the copywriter might listen for the questions that participants bring up about the product (Is it waterproof? How do I replace the batteries?) and make note of them to add to an FAQ or as part of a product description later. Participatory design is particularly useful for:

- Organizations building a product or application.

- Audiences who have very specific needs and strong opinions.

Learn more about participatory design.

A/B Testing

While most of the research recommendations on this list are intended for copywriters to put in place before they begin writing, A/B testing is a great method for improving copy. A/B testing can happen in two ways: moderated and unmoderated testing.

Moderated testing is not unlike a usability test: a researcher will typically meet with users and ask, “Which page do you prefer?” or “Tell me what you see on each page.” Moderated A/B testing can help the copywriter learn more specifically why users are drawn to one version rather than the other. However, unmoderated testing is also valuable. In unmoderated A/B testing, there is no researcher to facilitate the interaction. For example, users might navigate to a URL and be presented with either version of the screen. The team can then look at the analytics and see how many users directed to version A completed their goal, and how many users directed to version B completed theirs.

Whether moderated or unmoderated, A/B testing helps a copywriter refine terminology and wording to better reach the target audience. For example, a copywriter might try two headlines for a new security system. One is reassuring (“We’ll keep your family safe”) and the other is frightening (“Do you know what’s out there?”). A/B testing will show the copywriter which one is more successful. A/B testing is particularly useful for:

- Situations where the copywriter has a good sense of what to write, but is undecided between two styles or voices in the copy.

- Projects with a technical team who can work with the copywriter to set up A/B testing and analytics.

- Brand redesigns, with new styles for an already defined audience.

Learn more about A/B testing.

Tools For Writers

Once research is complete, it’s time to convert that user knowledge into actual writing. Some copywriters work when inspiration strikes; others simply plod through page after page. However, there are a number of tools available to make the process easier and more enjoyable. Because many are adapted from UX and content strategy, they’re intended to convert user research knowledge into copy that resonates with the people you’re writing for.

None of these tools are mandatory. They will each appeal to different types of writers, and you can pick and choose from them to accomplish different sorts of projects.

Personas

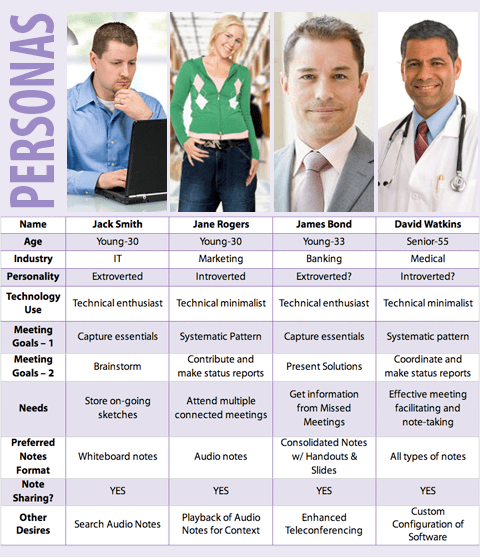

Personas are one way that user researchers put their research findings into an easy-to-use deliverable. A persona is an imaginary person intended to represent your target audience. The persona includes everything that makes this type of person distinct: their needs, wants, goals, expectations and frustrations. It’s important to note that a persona is only as useful as the research it is based on. In other words: don’t simply make up a persona! Create the persona with information garnered from interviews.

A persona generally includes a photo, a name, a job type, general age, and information about how the audience type spends his or her day. Be as specific as possible and then you can reference the persona any time you are struggling to remember who you’re writing for.

Once copywriters have a persona, they can call the persona by name, and think of the persona as a person. For example, at the bottom of a paragraph, copywriters might consider, “Now that Joe knows how much the lawnmower costs, what is he going to ask?” Whatever question Joe has, the next sentence can provide an answer. Personas are particularly useful for:

- A few different user types, all with specific goals.

- Users who feel very abstract.

Learn more about personas.

The Core Model

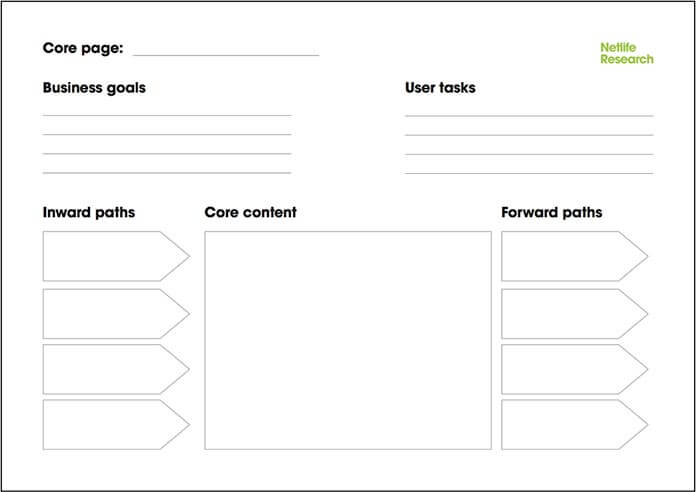

The core model, developed by information architect Are Halland, is a tool to help identify what content should go on a given page. This is particularly valuable when you’re struggling to understand why the company wants a specific page created. The core model also helps us to connect one page to the next, by asking for inward and forward paths (in other words, where is the user coming from, and where might they go from this page?).

Many content strategists provide stakeholders with core model worksheets to fill out. However, a copywriter can make these decisions just as well as a stakeholder. The core model connects business goals and user tasks, making it an excellent step before writing the actual content on a page.

A copywriter might start off by thinking about the inward paths: what page was the user (or persona) on before they came here? What triggered them to come to this page? What questions do they have now? If the persona came from the homepage, then the core content should help guide them to additional, more detailed pages, or product options. The core model is particularly useful for:

- Projects with clear business goals, but unclear user goals.

- Websites with many pages of content that don’t obviously connect to one another.

- Websites without a clear path for the user to take.

Learn more about the core model.

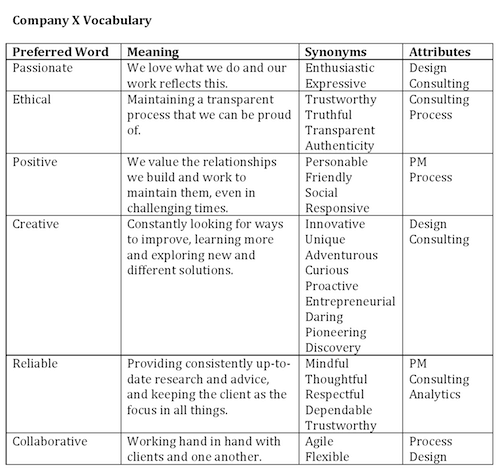

Nomenclature Charts

Many copywriters are provided with a list of keywords to use while writing. The keywords are generally determined by the marketing department to support SEO efforts, and can be verified during user interviews, focus groups or A/B testing. However, a nomenclature chart takes the keywords a step further. A nomenclature chart has four columns: the preferred term, the definition, synonyms, and related items.

The preferred term is the keyword, as defined by the stakeholders or marketing department. The definition is a place to write what the internal team means when they use that keyword — which is not necessarily the same as the dictionary definition! The synonyms section comes from user research, and is an opportunity for copywriters to add all of the terms that the target audience uses to refer to the same item. Lastly, the related items are just what they sound like: if the keyword is an adjective, the related items are products that the business wants that adjective to refer to.

A nomenclature chart gives meaning to the list of keywords, which makes it easier for copywriters to incorporate those terms in the page content. In addition, it helps bridge the gap between audience language and business language: you might choose to refer to the same item three times as the preferred term, but once as a popular synonym, to ensure the target audience recognizes it. Nomenclature charts are particularly useful in:

- Situations where the user speaks in a very different vocabulary, or has a very different background from the copywriter.

- Projects where the copywriter feels as though they are using the same adjective or phrase to describe everything.

Learn more about nomenclature and terminology.

For a copywriter, a nomenclature chart is a great reference point. When you feel that you’ve used the same word six times on a page, look at the nomenclature chart for alternatives.

Content Mapping

Templates are fantastic things. Content strategists love them, as they streamline the content process. Designers love them, because they simplify site cohesiveness. But for copywriters, a template can be stifling. How are you supposed to put original content together across multiple pages that all look and feel the same?

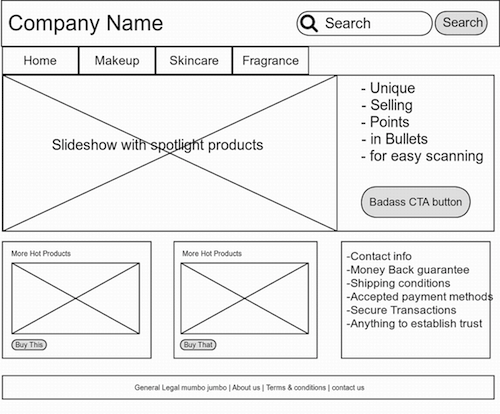

Content mapping is the solution. Content mapping is the process of looking at a template and determining where information about different things should go — literally mapping a piece of content to an area of a wireframe. Content strategists use mapping as a tool when they have a large amount of content and aren’t certain how it all fits together. Copywriters can take advantage of content mapping to see the site as a cohesive unit with related information spanning multiple pages.

For example, if the copywriter knows they want to write about the seven benefits of a product, and there are five pages each intended for a different audience, by mapping the seven benefits to each template, the copywriter can create a sense of consistency, and plan which benefits to mention on which pages. Content mapping is particularly useful for:

- Websites with a large number of pages.

- Projects with a lot of important content and no clear idea of where the content should live.

- Websites without a clear path for the user to take.

Learn more about content mapping.

The Five ‘W’s

“If you want to be a professional writer, you’ll need to get used to asking the five Ws: who, what, where, when and why.” I heard the advice (which goes back centuries!) over and over again as a student. Turns out it’s true, and even more useful when applied to a specific persona. When you’re at a loss for what to write or how to phrase it, go back to the basics.

- Who are you writing for?

- What is the main message you want to get across?

- Where does the action take place?

- When is it relevant?

- Why is it important? (i.e. what’s the goal?)

When you answer the five Ws, you identify the content that needs to be provided on a given page. Then, to write it, imagine the page as a conversation between you and your persona. For example, if you were writing to advertise an upcoming Little League game:

- Who: local parents of baseball players, and community friends.

- What: the Little League game is worth a $10 payment, because it will be a fun, warm, friendly way to spend an afternoon.

- Where: on the online forums before the game, and then at the downtown field.

- When: beginning now, and ending the week after the game, when the post-game lottery will be complete.

- Why: because the more people who attend the event, the more the community as a whole will benefit.

However, this same information would be written very differently when we write it for the children playing in the game:

- Who: you, the players.

- What: make sure you show up an hour early for the game.

- Where: on handouts at practice, or via email.

- When: beginning now and ending the day of the game.

- Why: because you need time to warm up before the game begins.

Asking and answering the five Ws are particularly useful for:

- Projects with a few distinct audiences.

- Any time the copywriter gets writer’s block.

Learn more about the five Ws.

Storytelling

Everyone gets writer’s block now and again, but no one ever gets speaker’s block. I once had a journalism professor who suggested I “try explaining [the topic] to a fifteen-year-old.” Once I had explained it, he asked me to break it down more. “Explain it to a ten-year-old.” This took a little more work. Next he had me “explain it to a five-year-old.”

It’s not just children who need different methods of storytelling. The same is true when we tell a story to a parent, a colleague, a mentor or a friend. When you’re feeling stuck, start talking aloud. Imagine you’re speaking to someone you know. Then try speaking to your persona. Getting the words flowing from your mouth will make it easier to get them down on paper.

For example, if I’m trying to explain why users should fill out a form on the contact page, I might start to get stuck. To jump-start my mind, I might go tell my co-worker why I’m building the form in the first place. That will give me the same introductory text that I need to include at the top of my page. Storytelling is particularly useful for:

- Highly complex or technical pages.

- Ideas that feel vague or abstract.

- Anything that the copywriter is struggling to put into words.

Learn more about storytelling.

With these tools, a copywriter can learn a great deal about the person who will be reading their copy. Of course, it’s important to remember that user research is not a magic wand. User research needs to be done carefully, to ensure the resulting knowledge is truly representative of users. As a copywriter, you can evaluate whether or not you’re seeing a representative sample by asking how many users were interviewed and how they were recruited.

Jump Into Research

Research should always influence our work. For copywriters, research is the key to creating content that engages and motivates our users, whether we’re writing homepage copy or press releases. Not every project has (or needs) a content strategist, but that’s no excuse for copywriters to write blindly.

If you have the opportunity, seek out a content strategist or a user researcher; if research has already been conducted, they’ll be happy to walk you through it, and if it hasn’t, then now is the time to get involved. Even just one or two of these research processes and tools will help you learn a great deal about your users, and ultimately it will improve your final content.

Additional Resources

If you’re interested in reading more about copywriting tools and creating a full content strategy, check out these resources.

- “The Step Before Writing”, by Bjørn Bergslien

- “The Core Model: Designing Inside Out for Better Results”, by Ida Aalen

- “Transformational Storytelling: Creating Meaning and Metrics”, by Brenda Huettner

- “10 Steps to Create Intelligent Content This Year”, by Julia McCoy

- “What UX Can Learn from Print”, by Mike Straus

- “The Discipline of Content Strategy”, by Kristina Halvorson

- Podcast: What “Intelligent Content” Means for B2B Copywriters, by Radix Communications

- “Creating Reusable Content”, by Karen McGrane

Further Reading

- A 5 Step Process For Conducting User Research

- 5 Copywriting Errors That Can Ruin A Company’s Website

- 50 Free Resources That Will Improve Your Writing Skills

- Designing The Words: Why Copy Is A Design Issue

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st