An Alternative Voice UI To Voice Assistants

For most people, the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of voice user interfaces are voice assistants, such as Siri, Amazon Alexa or Google Assistant. In fact, assistants are the only context where most people have ever used voice to interact with a computer system.

While voice assistants have brought voice user interfaces to the mainstream, the assistant paradigm is not the only, nor even the best way to use, design, and create voice user interfaces.

In this article, I’ll go through the issues voice assistants suffer from and present a new approach for voice user interfaces that I call direct voice interactions.

Voice Assistants Are Voice-Based Chatbots

A voice assistant is a piece of software that uses natural language instead of icons and menus as its user interface. Assistants typically answer questions and often proactively try to help the user.

Instead of straightforward transactions and commands, assistants mimic a human conversation and use natural language bi-directionally as the interaction modality, meaning it both takes input from the user and answers to the user by using natural language.

The first assistants were dialogue-based question-answering systems. One early example is Microsoft’s Clippy that infamously tried to aid users of Microsoft Office by giving them instructions based on what it thought the user was trying to accomplish. Nowadays, a typical use case for the assistant paradigm are chatbots, often used for customer support in a chat discussion.

Voice assistants, on the other hand, are chatbots that use voice instead of typing and text. The user input is not selections or text but speech and the response from the system is spoken out loud, too. These assistants can be general assistants such as Google Assistant or Alexa that can answer a multitude of questions in a reasonable way or custom assistants that are built for a special purpose such as fast-food ordering.

Although often the user’s input is just a word or two and can be presented as selections instead of actual text, as the technology evolves, the conversations will be more open-ended and complex. The first defining feature of chatbots and assistants is the use of natural language and conversational style instead of icons, menus, and transactional style that defines a typical mobile app or website user experience.

Recommended reading: Building A Simple AI Chatbot With Web Speech API And Node.js

The second defining characteristic that derives from the natural language responses is the illusion of a persona. The tone, quality, and language that the system uses define both the assistant experience, the illusion of empathy and susceptibility to service, and its persona. The idea of a good assistant experience is like being engaged with a real person.

Since voice is the most natural way for us to communicate, this might sound awesome, but there are two major problems with using natural language responses. One of these problems, related to how well computers can imitate humans, might be fixed in the future with the development of conversational AI technologies, but the problem of how human brains handle information is a human problem, not fixable in the foreseeable future. Let’s look into these problems next.

Two Problems With Natural Language Responses

Voice user interfaces are of course user interfaces that use voice as a modality. But voice modality can be used for both directions: for inputting information from the user and outputting information from the system back to the user. For example, some elevators use speech synthesis for confirming the user selection after the user presses a button. We’ll later discuss voice user interfaces that only use voice for inputting information and use traditional graphical user interfaces for showing the information back to the user.

Voice assistants, on the other hand, use voice for both input and output. This approach has two main problems:

Problem #1: Imitation Of A Human Fails

As humans, we have an innate inclination to attribute human-like features to non-human objects. We see the features of a man in a cloud drifting by or look at a sandwich and it seems like it’s grinning at us. This is called anthropomorphism.

This phenomenon applies to assistants too, and it is triggered by their natural language responses. While a graphical user interface can be built somewhat neutral, there’s no way a human could not start thinking about whether the voice of someone belongs to a young or an old person or whether they are male or a female. Because of this, the user almost starts to think that the assistant is indeed a human.

However, we humans are very good at detecting fakes. Strangely enough, the closer something comes to resembling a human, the more the small deviations start to disturb us. There is a feeling of creepiness towards something that tries to be human-like but does not quite measure up to it. In robotics and computer animations this is referred to as the “uncanny valley”.

The better and more human-like we try to make the assistant, the creepier and disappointing the user experience can be when something goes wrong. Everyone who has tried assistants has probably stumbled upon the problem of responding with something that feels idiotic or even rude.

The uncanny valley of voice assistants poses a problem of quality in assistant user experience that is hard to overcome. In fact, the Turing test (named after the famous mathematician Alan Turing) is passed when a human evaluator exhibiting a conversation between two agents cannot distinguish between which of them is a machine and which is a human. So far, it has never been passed.

This means that the assistant paradigm sets a promise of a human-like service experience that can never be fulfilled and the user is bound to get disappointed. The successful experiences only build up the eventual disappointment, as the user begins to trust their human-like assistant.

Problem 2: Sequential And Slow Interactions

The second problem of voice assistants is that the turn-based nature of natural language responses causes delay to the interaction. This is due to how our brains process information.

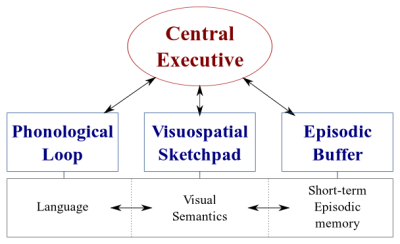

There are two types of data processing systems in our brains:

- A linguistic system that processes speech;

- A visuospatial system that specializes in processing visual and spatial information.

These two systems can operate in parallel, but both systems process only one thing at a time. This is why you can speak and drive a car at the same time, but you can’t text and drive because both of those activities would happen in the visuospatial system.

Similarly, when you are talking to the voice assistant, the assistant needs to stay quiet and vice versa. This creates a turn-based conversation, where the other part is always fully passive.

However, consider a difficult topic you want to discuss with your friend. You’d probably discuss face-to-face rather than over the phone, right? That is because in a face-to-face conversation we use non-verbal communication to give realtime visual feedback to our conversation partner. This creates a bi-directional information exchange loop and enables both parties to be actively involved in the conversation simultaneously.

Assistants don’t give realtime visual feedback. They rely on a technology called end-pointing to decide when the user has stopped talking and replies only after that. And when they do reply, they don’t take any input from the user at the same time. The experience is fully unidirectional and turn-based.

In a bi-directional and realtime face-to-face conversation, both parties can react immediately to both visual and linguistic signals. This utilizes the different information processing systems of the human brain and the conversation becomes smoother and more efficient.

Voice assistants are stuck in unidirectional mode because they are using natural language both as the input and output channels. While voice is up to four times faster than typing for input, it’s significantly slower to digest than reading. Because information needs to be processed sequentially, this approach only works well for simple commands such as “turn off the lights” that don’t require much output from the assistant.

Earlier, I promised to discuss voice user interfaces that employ voice only for inputting data from the user. This kind of voice user interfaces benefit from the best parts of voice user interfaces — naturalness, speed and ease-of-use — but don’t suffer from the bad parts — uncanny valley and sequential interactions

Let’s consider this alternative.

A Better Alternative To The Voice Assistant

The solution to overcome these problems in voice assistants is letting go of natural language responses, and replacing them with realtime visual feedback. Switching feedback to visual will enable the user to give and get feedback simultaneously. This will enable the application to react without interrupting the user and enabling a bidirectional information flow. Because the information flow is bidirectional, its throughput is bigger.

Currently, the top use cases for voice assistants are setting alarms, playing music, checking the weather, and asking simple questions. All of these are low-stakes tasks that don’t frustrate the user too much when failing.

As David Pierce from the Wall Street Journal once wrote:

“I can’t imagine booking a flight or managing my budget through a voice assistant, or tracking my diet by shouting ingredients at my speaker.”

— David Pierce from Wall Street Journal

These are information-heavy tasks that need to go right.

However, eventually, the voice user interface will fail. The key is to cover this as fast as possible. A lot of errors happen when typing on a keyboard or even in a face-to-face conversation. However, this is not at all frustrating as the user can recover simply by clicking the backspace and trying again or asking for clarification.

This fast recovery from errors enables the user to be more efficient and doesn’t force them into a weird conversation with an assistant.

Direct Voice Interactions

In most applications, actions are performed through manipulating graphical elements on the screen, through poking or swiping (on touchscreens), clicking a mouse, and/or pressing buttons on a keyboard. Voice input can be added as an additional option or modality for manipulating these graphical elements. This type of interaction can be called direct voice interaction.

The difference between direct voice interactions and assistants is that instead of asking an avatar, the assistant, to perform a task, the user directly manipulates the graphical user interface with voice.

“Isn’t this semantics?”, you might ask. If you are going to talk to the computer does it really matter if you are talking directly to the computer or through a virtual persona? In both cases, you are just talking to a computer!

Yes, the difference is subtle, but critical. When clicking a button or menu item in a GUI (Graphical User Interface) it is blatantly obvious that we are operating a machine. There is no illusion of a person. By replacing that clicking with a voice command, we are improving the human-computer interaction. With the assistant paradigm, on the other hand, we are creating a deteriorated version of the human-to-human interaction and hence, journeying into the uncanny valley.

Blending voice functionalities into the graphical user interface also offers the potential to harness the power of different modalities. While the user can use voice to operate the application, they have the ability to use the traditional graphical interface, too. This enables the user to switch between touch and voice seamlessly and choose the best option based on their context and task.

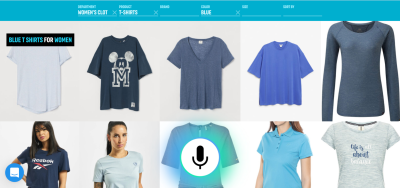

For example, voice is a very efficient method for inputting rich information. Selecting between a couple of valid alternatives, touch or click is probably better. The user can then replace typing and browsing by saying something like, “Show me flights from London to New York departing tomorrow,” and select the best option from the list by using touch.

Now you might ask “OK, this looks great, so why haven’t we seen examples of such voice user interfaces before? Why aren’t the major tech companies creating tools for something like this?” Well, there are probably many reasons for that. One reason is that the current voice assistant paradigm is probably the best way for them to leverage the data they get from the end-users. Another reason has to do with the way their voice technology is built.

A well-working voice user interface requires two distinct parts:

- Speech recognition that turns speech into text;

- Natural language understanding components that extract meaning from that text.

The second part is the magic that turns utterances “Turn off the living room lights” and “Please switch off the lights in the living room” into the same action.

Recommended reading: How To Build Your Own Action For Google Home Using API.AI

If you’ve ever used an assistant with a display (such as Siri or Google Assistant), you’ve probably noticed that you do get the transcript in near realtime, but after you’ve stopped speaking it takes a few seconds before the system actually performs the action you’ve requested. This is due to both speech recognition and natural language understanding taking place sequentially.

Let’s see how this could be changed.

Realtime Spoken Language Understanding: The Secret Sauce To More Efficient Voice Commands

How fast an application reacts to user input is a major factor in the overall user experience of the application. The most important innovation of the original iPhone was the extremely responsive and reactive touch screen. The ability of a voice user interface to react to voice input instantaneously is equally important.

In order to establish a fast bi-directional information exchange loop between the user and the UI, the voice-enabled GUI should be able to instantly react — even mid-sentence — whenever the user says something actionable. This requires a technique called streaming spoken language understanding.

Contrary to the traditional turn-based voice assistant systems that wait for the user to stop talking before processing the user request, systems using streaming spoken language understanding actively try to comprehend the user intent from the very moment the user starts to talk. As soon as the user says something actionable, the UI instantly reacts to it.

The instant response immediately validates that the system is understanding the user and encourages the user to go on. It’s analogous to a nod or a short “a-ha” in human-to-human communication. This results in longer and more complex utterances supported. Respectively, if the system does not understand the user or the user misspeaks, instant feedback enables fast recovery. The user can immediately correct and continue, or even verbally correct themself: “I want this, no I meant, I want that.” You can try this kind of application yourself in our voice search demo.

As you can see in the demo, the realtime visual feedback enables the user to correct themselves naturally and encourages them to continue with the voice experience. As they are not confused by a virtual persona, they can relate to possible errors in a similar way to typos — not as personal insults. The experience is faster and more natural because the information fed to the user is not limited by the typical rate of speech of about 150 words per minute.

Recommended reading: Designing Voice Experiences by Lyndon Cerejo

Conclusions

While voice assistants have been by far the most common use for voice user interfaces so far, the use of natural language responses makes them inefficient and unnatural. Voice is a great modality for inputting information, but listening to a machine talking is not very inspiring. This is the big issue of voice assistants.

The future of voice should therefore not be in conversations with a computer but in replacing tedious user tasks with the most natural way of communicating: speech. Direct voice interactions can be used to improve form filling experience in web or mobile applications, to create better search experiences, and to enable a more efficient way to control or navigate in an application.

Designers and app developers are constantly looking for ways to reduce friction in their apps or websites. Enhancing the current graphical user interface with a voice modality would enable multiple times faster user interactions especially in certain situations such as when the end-user is on mobile and on the go and typing is hard. In fact, voice search can be up to five times faster than a traditional search filtering user interface, even when using a desktop computer.

Next time, when you are thinking about how you can make a certain user task in your application easier to use, more enjoyable to use, or you are interested in increasing conversions, consider whether that user task can be described accurately in natural language. If yes, complement your user interface with a voice modality but don’t force your users to conversate with a computer.

Resources

- “Voice First Versus The Multimodal User Interfaces Of The Future,” Joan Palmiter Bajorek, UXmatters

- “Guidelines For Creating Productive Voice-Enabled Apps,” Hannes Heikinheimo, Speechly

- “6 Reasons Your Touch-Screen Apps Should Have Voice Capabilities,” Ottomatias Peura, UXmatters

- Mixing Tangible And Intangible: Designing Multimodal Interfaces Using Adobe XD, Nick Babich, Smashing Magazine

(Adobe XD can be for prototyping something similar) - “Efficiency At The Speed Of Sound: The Promise Of Voice-Enabled Operations,” Eric Turkington, RAIN

- A demo showcasing realtime visual feedback in eCommerce voice search filtering (video version)

- Speechly provides developer tools for this kind of user interfaces

- Open source alternative: voice2json

Take a break with a 3D game built on Netlify!

Take a break with a 3D game built on Netlify! Check the frontend report!

Check the frontend report!

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Start with a free demo —

Start with a free demo —