Beyond The Browser: From Web Apps To Desktop Apps

I started out as a web developer, and that’s now one part of what I do as a full-stack developer, but never had I imagined I’d create things for the desktop. I love the web. I love how altruistic our community is, how it embraces open-source, testing and pushing the envelope. I love discovering beautiful websites and powerful apps. When I was first tasked with creating a desktop app, I was apprehensive and intimidated. It seemed like it would be difficult, or at least… different.

It’s not an attractive prospect, right? Would you have to learn a new language or three? Imagine an archaic, alien workflow, with ancient tooling, and none of those things you love about the web. How would your career be affected?

OK, take a breath. The reality is that, as a web developer, not only do you already possess all of the skills to make great modern desktop apps, but thanks to powerful new APIs at your disposal, the desktop is actually where your skills can be leveraged the most.

In this article, we’ll look at the development of desktop applications using NW.js and Electron, the ups and downs of building one and living with one, using one code base for the desktop and the web, and more.

Why?

First of all, why would anyone create a desktop app? Any existing web app (as opposed to a website, if you believe in the distinction) is probably suited to becoming a desktop app. You could build a desktop app around any web app that would benefit from integration in the user’s system; think native notifications, launching on startup, interacting with files, etc. Some users simply prefer having certain apps there permanently on their machine, accessible whether they have a connection or not.

Maybe you’ve an idea that would only work as a desktop app; some things simply aren’t possible with a web app (at least yet, but more about that in a little bit). You could create a self-contained utility app for internal company use, without requiring anyone to install anything other than your app (because Node.js in built-in). Maybe you’ve an idea for the Mac App Store. Maybe it would simply be a fun side project.

It’s hard to sum up why you should consider creating a desktop app because there are so many kinds of apps you could create. It really depends on what you’d like to achieve, how advantageous you find the additional APIs, and how much offline usage would enhance the experience for your users. For my team, it was a no-brainer because we were building a chat application. On the other hand, a connection-dependent desktop app that doesn’t really have any desktop integration should be a web app and a web app alone. It wouldn’t be fair to expect a user to download your app (which includes a browser of its own and Node.js) when they wouldn’t get any more value from it than from visiting a URL of yours in their favorite browser.

Instead of describing the desktop app you personally should build and why, I’m hoping to spark an idea or at least spark your interest in this article. Read on to see just how easy it is to create powerful desktop apps using web technology and what that can afford you over (or alongside of) creating a web app.

NW.js

Desktop applications have been around a long time but you don’t have all day, so let’s skip some history and begin in Shanghai, 2011. Roger Wang, of Intel’s Open Source Technology Center, created node-webkit; a proof-of-concept Node.js module that allowed the user to spawn a WebKit browser window and use Node.js modules within <script> tags.

After some progress and a switch from WebKit to Chromium (the open-source project Google Chrome is based on), an intern named Cheng Zhao joined the project. It was soon realized that an app runtime based on Node.js and Chromium would make a nice framework for building desktop apps. The project went on be quite popular.

Note: node-webkit was later renamed NW.js to make it a bit more generic because it no longer used Node.js or WebKit. Instead of Node.js, it was based on io.js (the Node.js fork) at the time, and Chromium had moved on from WebKit to its own fork, Blink.

So, if you were to download an NW.js app, you would actually be downloading Chromium, plus Node.js, plus the actual app code. Not only does this mean a desktop app can be created using HTML, CSS and JavaScript, but the app would also have access to all of the Node.js APIs (to read and write to disk, for example), and the end user wouldn’t know any better. That’s pretty powerful, but how does it work? Well, first let’s take a look at Chromium.

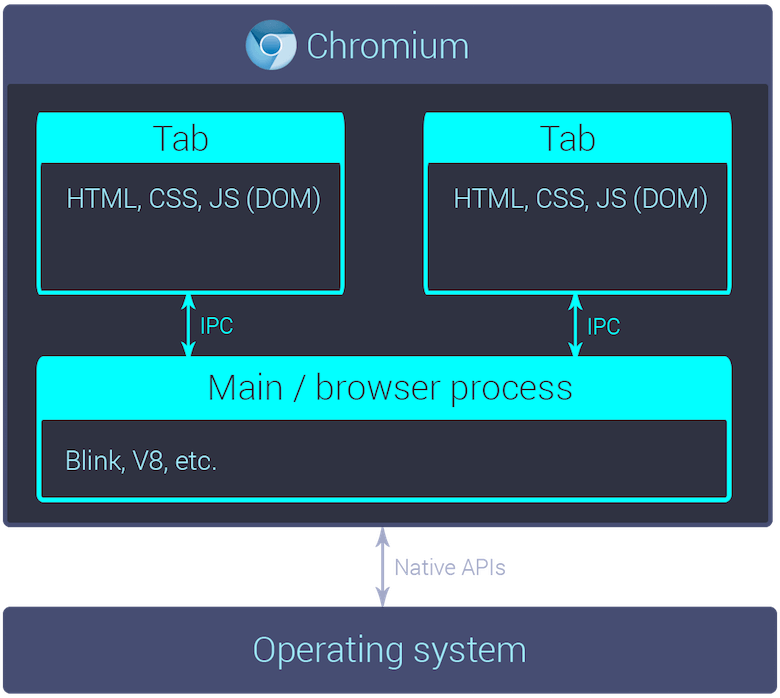

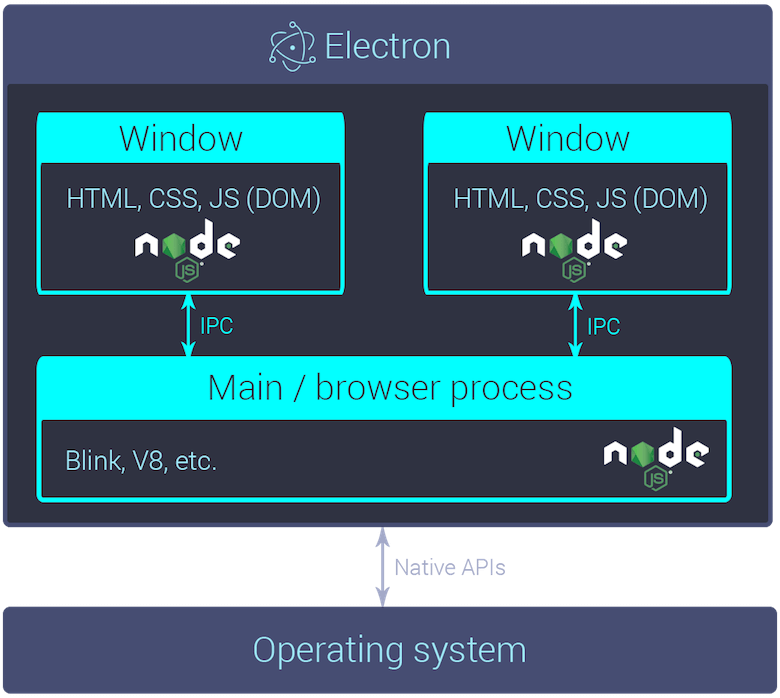

There is a main background process, and each tab gets its own process. You might have seen that Google Chrome always has at least two processes in Windows’ task manager or macOS’ activity monitor. I haven’t even attempted to arrange the contents of the main process here, but it contains the Blink rendering engine, the V8 JavaScript engine (which is what Node.js is built on, too, by the way) and some platform APIs that abstract native APIs. Each isolated tab or renderer process has access to the JavaScript engine, CSS parser and so on, but it is completely separate to the main process for fault tolerance. Renderer processes interact with the main process through interprocess communication (IPC).

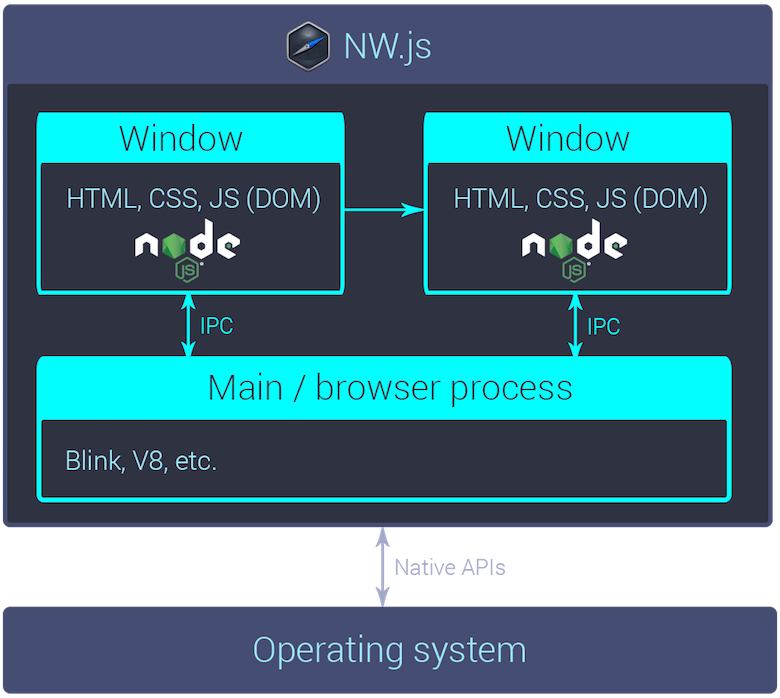

This is roughly what an NW.js app looks like. It’s basically the same, except that each window has access to Node.js now as well. So, you have access to the DOM and you can require other scripts, node modules you’ve installed from npm, or built-in modules provided by NW.js. By default, your app has one window, and from there you can spawn other windows.

Creating an app is really easy. All you need is an HTML file and a package.json, like you would have when working with Node.js. You can create a default one by running npm init –yes. Typically, a package.json would point a JavaScript file as the “main” file for the module (i.e. using the main property), but with NW.js you need to edit the main property to point to your HTML file.

{

"name": "example-app",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.html",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"keywords": [],

"author": "",

"license": "ISC"

}

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example app</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</body>

</html>

Once you install the official nw package from npm (by running npm install -g nw), you can run nw . within the project directory to launch your app.

It’s as easy as that. So, what happened here was that NW.js opened the initial window, loading your HTML file. I know this doesn’t look like much, but it’s up to you add some markup and styles, just like you would in a web app.

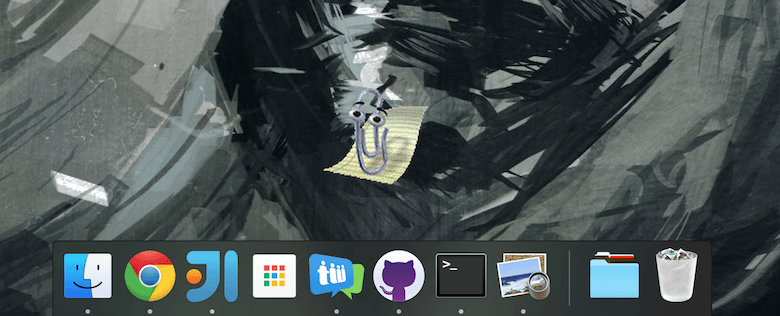

You could drop the window bar and chrome if you like, or create your own custom frame. You could have semi to fully transparent windows, hidden windows and more. I took this a bit further recently and resurrected Clippy using NW.js. There’s something weirdly satisfying about seeing Clippy on macOS or Windows 10.

So, you get to write HTML, CSS and JavaScript. You can use Node.js to read and write to disk, execute system commands, spawn other executables and more. Hypothetically, you could build a multiplayer roulette game over WebRTC that deletes some of the users’ files randomly, if you wanted.

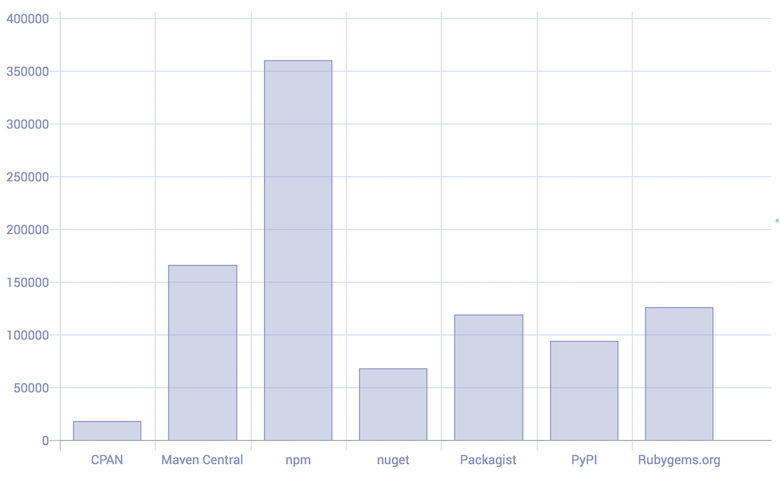

You get access not only to Node.js’ APIs but to all of npm, which has over 350,000 modules now. For example, auto-launch is an open-source module we created at Teamwork.com to launch an NW.js or Electron app on startup.

Node.js also has what’s known as “native modules,” which, if you really need to do something a bit lower level, allows you to create modules in C or C++.

To top it all off, NW.js exposes APIs that effectively wrap native APIs, allowing you to integrate closely with the desktop environment. You can have a tray icon, open a file or URL in the default system application, and a lot lot more. All you need to do to trigger a notification is use the HTML5 notification API:

new Notification('Hello', {

body: 'world'

});

Electron

You might recognize GitHub’s text editor, Atom, below. Whether you use it or not, Atom was a game-changer for desktop apps. GitHub started development of Atom in 2013, soon recruited Cheng Zhao, and forked node-webkit as its base, which it later open-sourced under the name atom-shell.

Note: It’s disputed whether Electron is a fork of node-webkit or whether everything was rewritten from scratch. Either way, it’s effectively a fork for the end user because the APIs were almost identical.

In making Atom, GitHub improved on the formula and ironed out a lot of the bugs. In 2015, atom-shell was renamed Electron. Since then it has hit version 1.0, and with GitHub pushing it, it has really taken off.

As well as Atom, other notable projects built with Electron include Slack, Visual Studio Code, Brave, HyperTerm and Nylas, which is really doing some cutting-edge stuff with it. Mozilla Tofino is an interesting one, too. It was an internal project at Mozilla (the company behind Firefox), with the aim of radically improving web browsers. Yeah, a team within Mozilla chose Electron (which is based on Chromium) for this experiment.

How Does It Differ?

But how is it different from NW.js? First of all, Electron is less browser-oriented than NW.js. The entry point for an Electron app is a script that runs in the main process.

The Electron team patched Chromium to allow for the embedding of multiple JavaScript engines that could run at the same time. So, when Chromium releases a new version, they don’t have to do anything.

Note: NW.js hooks into Chromium a little differently, and this was often blamed on the fact NW.js wasn’t quite as good at keeping up with Chromium as Electron was. However, throughout 2016, NW.js has released a new version within 24 hours of each major Chromium release, which the team attributes to an organizational shift.

Back to the main process. Your app hasn’t any window by default, but you can open as many windows as you’d like from the main process, each having its own renderer process, just like NW.js.

So, yeah, the minimum you need for an Electron app is a main JavaScript file (which we’ll leave empty for now) and a package.json that points to it. Then, all you need to do is npm install –save-dev electron and run electron . to launch your app.

{

"name": "example-app",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "main.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"keywords": [],

"author": "",

"license": "ISC"

}

// main.js, which is empty

Not much will happen, though, because your app hasn’t any window by default. You can open as many windows as you’d like from the main process, each having its own renderer process, just like they’d have in an NW.js app.

// main.js

const {app, BrowserWindow} = require('electron');

let mainWindow;

app.on('ready', () => {

mainWindow = new BrowserWindow({

width: 500,

height: 400

});

mainWindow.loadURL('file://' + __dirname + '/index.html');

});

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example app</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</body>

</html>

You could load a remote URL in this window, but typically you’d create a local HTML file and load that. Ta-da!

Of the built-in modules Electron provides, like the app or BrowserWindow module used in the previous example, most can only be used in either the main or a renderer process. For example, the main process is where, and only where, you can manage your windows, automatic updates and more. You might want a click of a button to trigger something in your main process, though, so Electron comes with built-in methods for IPC. You can basically emit arbitrary events and listen for them on the other side. In this case, you’d catch the click event in the renderer process, emit an event over IPC to the main process, catch it in the main process and finally perform the action.

OK, so Electron has distinct processes, and you have to organize your app slightly differently, but that’s not a big deal. Why are people using Electron instead of NW.js? Well, there’s mindshare. So many related tools and modules are out there as a result of its popularity. The documentation is better. Most importantly, it has fewer bugs and superior APIs.

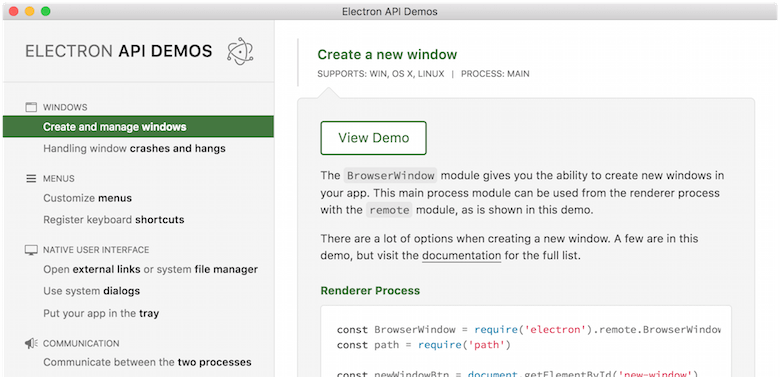

Electron’s documentation really is amazing, though — that’s worth emphasizing. Take the Electron API Demos app. It’s an Electron app that interactively demonstrates what you can do with Electron’s APIs. Not only is the API described and sample code provided for creating a new window, for example, but clicking a button will actually execute the code and a new window will open.

If you submit an issue via Electron’s bug tracker, you’ll get a response within a couple of days. I’ve seen three-year-old NW.js bugs, although I don’t hold it against them. It’s tough when an open-source project is written in languages drastically different from the languages known by its users. NW.js and Electron are written mostly in C++ (and a tiny bit of Objective C++) but used by people who write JavaScript. I’m extremely grateful for what NW.js has given us.

Electron ironed out a few of the flaws in the NW.js APIs. For example, you can bind global keyboard shortcuts, which would be caught even if your app isn’t focused. An example API flaw I ran into was that binding to Control + Shift + A in an NW.js app did what you would expect on Windows, but actually bound to Command + Shift + A on a Mac. This was intentional but really weird. There was no way to bind to the Control key. Also, binding to the Command key did bind to the Command key but the Windows key on Windows and Linux as well. The Electron team spotted these problems (when adding shortcuts to Atom I assume) and quickly updated their globalShortcut API so both of these cases work as you’d expect. To be fair, NW.js has since fixed the former but not the latter.

There are a few other differences. For instance, in recent NW.js versions, notifications that were previously native are now Chrome-style ones. These don’t go into the notification centre on Mac OS X or Windows 10, but there are modules on npm that you could use as a workaround if you’d like. If you want to do something interesting with audio or video, use Electron, because some codecs don’t work out of the box with NW.js.

Electron has added a few new APIs as well, more desktop integration, and it has built-in support for automatic updates, but I’ll cover that later.

But How Does It Feel?

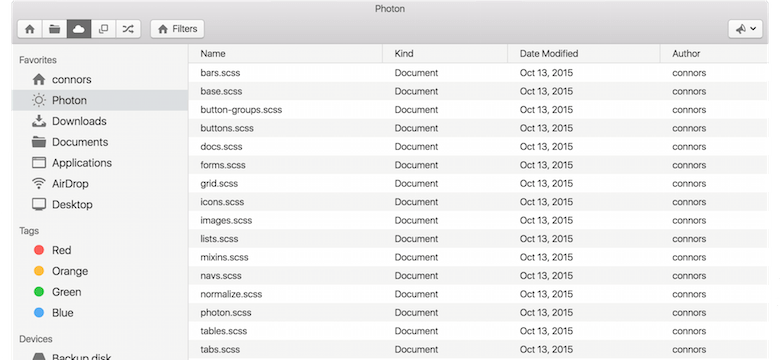

It feels fine. Sure, it’s not native. Most desktop apps these days don’t look like Windows Explorer or Finder anyway, so users won’t mind or realize that HTML is behind your user interface. You can make it feel more native if you’d like, but I’m not convinced it will make the experience any better. For example, you could prevent the cursor from turning to a hand when the user hovers over a button. That’s how a native desktop app would act, but is that better? There are also projects out there like Photon Kit, which is basically a CSS framework like Bootstrap, but for macOS-style components.

Performance

What about performance? Is it slow or laggy? Well, your app is essentially a web app. It’ll perform pretty much like a web app in Google Chrome. You can create a performant app or a sluggish one, but that’s fine because you already have the skills to analyze and improve performance. One of the best things about your app being based on Chromium is that you get its DevTools. You can debug within the app or remotely, and the Electron team has even created a DevTools extension named Devtron to monitor some Electron-specific stuff.

Your desktop app can be more performant than a web app, though. One thing you could do is create a worker window, a hidden window that you use to perform any expensive work. Because it’s an isolated process, any computation or processing going on in that window won’t affect rendering, scrolling or anything else in your visible window(s).

Keep in mind that you can always spawn system commands, spawn executables or drop down to native code if you really need to (you won’t).

Distribution

Both NW.js and Electron support a wide array of platforms, including Windows, Mac and Linux. Electron doesn’t support Windows XP or Vista; NW.js does. Getting an NW.js app into the Mac App Store is a bit tricky; you’ll have to jump through a few hoops. Electron, on the other hand, comes with Mac App Store-compatible builds, which are just like the normal builds except that you don’t have access to some modules, such as the auto-updater module (which is fine because your app will update via the Mac App Store anyway).

Electron even supports ARM builds, so your app can run on a Chromebook or Raspberry Pi. Finally, Google may be phasing out Chrome Packaged Apps, but NW.js allows you to port an app over to an NW.js app and still have access the same Chromium APIs.

Even though 32-bit and 64-bit builds are supported, you’ll get away with 64-bit Mac and Windows apps. You will need 32-bit and 64-bit Linux apps, though, for compatibility.

So, let’s say that Electron has won over and you want to ship an Electron app. There’s a nice Node.js module named electron-packager that helps with packing your app up into an .app or .exe file. A few similar projects exist, including interactive ones that prompt you step by step. You should use electron-builder, though, which builds on top of electron-packager, plus a few other related modules. It generates .dmgs and Windows installers and takes care of the code-signing of your app for you. This is really important. Without it, your app would be labelled as untrusted by operating systems, your app could trigger anti-virus software, and Microsoft SmartScreen might try to block the user from launching your app.

The annoying thing about code-signing is that you have to sign your app on a Mac for Mac and on Windows for Windows. So, if you’re serious about shipping desktop apps, then you’ll need to build on multiple machines for each release.

This can feel a bit too manual or tedious, especially if you’re used to creating for the web. Thankfully, electron-builder was created with automation in mind. I’m talking here about continuous integration tools and services such as Jenkins, CodeShip, Travis-CI, AppVeyor (for Windows) and so on. These could run your desktop app build at the press of a button or at every push to GitHub, for example.

Automatic Updates

NW.js doesn’t have automatic update support, but you’ll have access to all of Node.js, so you can do whatever you want. Open-source modules are out there for it, such as node-webkit-updater, which handles downloading and replacing your app with a newer version. You could also roll your own custom system if you wanted.

Electron has built-in support for automatic updates, via its autoUpdater API. It doesn’t support Linux, first of all; instead, publishing your app to Linux package managers is recommended. This is common on Linux — don’t worry. The autoUpdater API is really simple; once you give it a URL, you can call the checkForUpdates method. It’s event-driven, so you can subscribe to the update-downloaded event, for example, and once it’s fired, call the restartAndInstall method to install the new version and restart the app. You can listen for a few other events, which you can use to tie the auto-updating functionality into your user interface nicely.

Note: You can have multiple update channels if you want, such as Google Chrome and Google Chrome Canary.

It’s not quite as simple behind the API. It’s based on the Squirrel update framework, which differs drastically between Mac and Windows, which use the Squirrel.Mac and Squirrel.Windows projects, respectively.

The update code within your Mac Electron app is simple, but you’ll need a server (albeit a simple server). When you call the autoUpdater module’s checkForUpdates method, it will hit your server. What your server needs to do is return a 204 (“No Content”) if there isn’t an update; and if there is, it needs to return a 200 with a JSON containing a URL pointing to a .zip file. Back under the hood of your app (or the client), Squirrel.Mac will know what to do. It’ll go get that .zip, unzip it and fire the appropriate events.

There a bit more (magic) going on in your Windows app when it comes to automatic updates. You won’t need a server, but you can have one if you’d like. You could host the static (update) files somewhere, such as AWS S3, or even have them locally on your machine, which is really handy for testing. Despite the differences between Squirrel.Mac and Squirrel.Windows, a happy medium can be found; for example, having a server for both, and storing the updates on S3 or somewhere similar.

Squirrel.Windows has a couple of nice features over Squirrel.Mac as well. It applies updates in the background; so, when you call restartAndInstall, it’ll be a bit quicker because it’s ready and waiting. It also supports delta updates. Let’s say your app checks for updates and there is one newer version. A binary diff (between the currently installed app and the update) will be downloaded and applied as a patch to the current executable, instead of replacing it with a whole new app. It can even do that incrementally if you’re, say, three versions behind, but it will only do that if it’s worth it. Otherwise, if you’re, say, 15 versions behind, it will just download the latest version in its entirety instead. The great thing is that all of this is done under the hood for you. The API remains really simple. You check for updates, it will figure out the optimal method to apply the update, and it will let you know when it’s ready to go.

Note: You will have to generate those binary diffs, though, and host them alongside your standard updates. Thankfully, electron-builder generates these for you, too.

Thanks to the Electron community, you don’t have to build your own server if you don’t want to. There are open-source projects you can use. Some allow you to store updates on S3 or use GitHub releases, and some even go as far as providing administrative dashboards to manage the updates.

Desktop Versus Web

So, how does making a desktop app differ from making a web app? Let’s look at a few unexpected problems or gains you might come across along the way, some unexpected side effects of APIs you’re used to using on the web, workflow pain points, maintenance woes and more.

Well, the first thing that comes to mind is browser lock-in. It’s like a guilty pleasure. If you’re making a desktop app exclusively, you’ll know exactly which Chromium version all of your users are on. Let your imagination run wild; you can use flexbox, ES6, pure WebSockets, WebRTC, anything you want. You can even enable experimental features in Chromium for your app (i.e. features coming down the line) or tweak settings such as your localStorage allowance. You’ll never have to deal with any cross-browser incompatibilities. This is on top of Node.js’ APIs and all of npm. You can do anything.

Note: You’ll still have to consider which operating system the user is running sometimes, though, but OS-sniffing is a lot more reliable and less frowned upon than browser sniffing.

Working With file://

Another interesting thing is that your app is essentially offline-first. Keep that in mind when creating your app; a user can launch your app without a network connection and your app will run; it will still load the local files. You’ll need to pay more attention to how your app behaves if the network connection is lost while it’s running. You may need to adjust your mindset.

Note: You can load remote URLs if you really want, but I wouldn’t.

One tip I can give you here is not to trust navigator.onLine completely. This property returns a Boolean indicating whether or not there’s a connection, but watch out for false positives. It’ll return true if there’s any local connection without validating that connection. The Internet might not actually be accessible; it could be fooled by a dummy connection to a Vagrant virtual machine on your machine, etc. Instead, use Sindre Sorhus’ is-online module to double-check; it will ping the Internet’s root servers and/or the favicon of a few popular websites. For example:

const isOnline = require('is-online');

if(navigator.onLine){

// hmm there's a connection, but is the Internet accessible?

isOnline().then(online => {

console.log(online); // true or false

});

}

else {

// we can trust navigator.onLine when it says there is no connection

console.log(false);

}

Speaking of local files, there are a few things to be aware of when using the file:// protocol — protocol-less URLs, for one; you can’t use them anymore. I mean URLs that start with // instead of https:// or https://. Typically, if a web app requests //example.com/hello.json, then your browser would expand this to https://example.com/hello.json or to https://example.com/hello.json if the current page is loaded over HTTPS. In our app, the current page would load using the file:// protocol; so, if we requested the same URL, it would expand to file://example.com/hello.json and fail. The real worry here is third-party modules you might be using; authors aren’t thinking of desktop apps when they make a library.

You’d never use a CDN. Loading local files is basically instantaneous. There’s also no limit on the number of concurrent requests (per domain), like there is on the web (with HTTP/1.1 at least). You can load as many as you want in parallel.

Artifacts Galore

A lot of asset generation is involved in creating a solid desktop app. You’ll need to generate executables and installers and decide on an auto-update system. Then, for each update, you’ll have to build the executables again, more installers (because if someone goes to your website to download it, they should get the latest version) and binary diffs for delta updates.

Weight is still a concern. A “Hello, World!” Electron app is 40 MB zipped. Besides the typical advice you follow when creating a web app (write less code, minify it, have fewer dependencies, etc.), there isn’t much I can offer you. The “Hello, World!” app is literally an app containing one HTML file; most of the weight comes from the fact that Chromium and Node.js are baked into your app. At least delta updates will reduce how much is downloaded when a user performs an update (on Windows only, I’m afraid). However, your users won’t be downloading your app on a 2G connection (hopefully!).

Expect The Unexpected

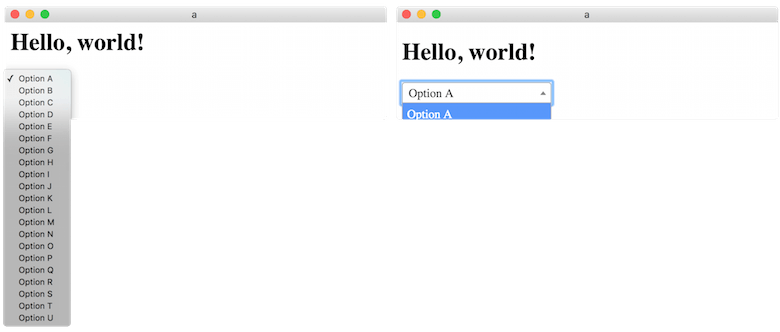

You will discover unexpected behavior now and again. Some of it is more obvious than the rest, but a little annoying nonetheless. For example, let’s say you’ve made a music player app that supports a mini-player mode, in which the window is really small and always in front of any other apps. If a user were to click or tap a dropdown (<select/>), then it would open to reveal its options, overflowing past the bottom edge of the app. If you were to use a non-native select library (such as select2 or chosen), though, you’re in trouble. When open, your dropdown will be cut off by the edge of your app. So, the user would see a few items and then nothing, which is really frustrating. This would happen in a web browser, too, but it’s not often the user would resize the window down to a small enough size.

You may or may not know it, but on a Mac, every window has a header and a body. When a window isn’t focused, if you hover over an icon or button in the header, its appearance will reflect the fact that it’s being hovered over. For example, the close button on macOS is gray when the window is blurred but red when you hover over it. However, if you move your mouse over something in the body of the window, there is no visible change. This is intentional. Think about your desktop app, though; it’s Chromium missing the header, and your app is the web page, which is the body of the window. You could drop the native frame and create your own custom HTML buttons instead for minimize, maximize and close. If your window isn’t focused, though, they won’t react if you were to hover over them. Hover styles won’t be applied, and that feels really wrong. To make it worse, if you were to click the close button, for example, it would focus the window and that’s it. A second click would be required to actually click the button and close the app.

To add insult to injury, Chromium has a bug that can mask the problem, making you think it works as you might have originally expected. If you move your mouse fast enough (nothing too unreasonable) from outside the window to an element inside the window, hover styles will be applied to that element. It’s a confirmed bug; applying the hover styles on a blurred window body “doesn’t meet platform expectations,” so it will be fixed. Hopefully, I’m saving you some heartbreak here. You could have a situation in which you’ve created beautiful custom window controls, yet in reality a lot of your users will be frustrated with your app (and will guess it’s not native).

So, you must use native buttons on a Mac. There’s no way around that. For an NW.js app, you must enable the native frame, which is the default anyway (you can disable it by setting window object’s frame property to false in your package.json).

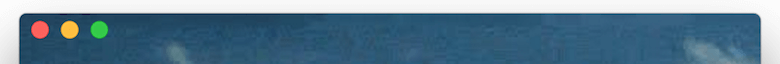

You could do the same with an Electron app. This is controlled by setting the frame property when creating a window; for example, new BrowserWindow({width: 800, height: 600, frame: true}). As the Electron team does, they spotted this issue and added another option as a nice compromise; titleBarStyle. Setting this to hidden will hide the native title bar but keep the native window controls overlaid over the top-left corner of your app. This gets you around the problem of having non-native buttons on Mac, but you can still style the top of the app (and the area behind the buttons) however you like.

// main.js

const {app, BrowserWindow} = require('electron');

let mainWindow;

app.on('ready', () => {

mainWindow = new BrowserWindow({

width: 500,

height: 400,

titleBarStyle: 'hidden'

});

mainWindow.loadURL('file://' + __dirname + '/index.html');

});

Here’s an app in which I’ve disabled the title bar and given the html element a background image:

See “Frameless Window” from Electron’s documentation for more.

Tooling

Well, you can pretty much use all of the tooling you’d use to create a web app. Your app is just HTML, CSS and JavaScript, right? Plenty of plugins and modules are out there specifically for desktop apps, too, such as Gulp plugins for signing your app, for example (if you didn’t want to use electron-builder). Electron-connect watches your files for changes, and when they occur, it’ll inject those changes into your open window(s) or relaunch the app if it was your main script that was modified. It is Node.js, after all; you can pretty much do anything you’d like. You could run webpack inside your app if you wanted to — I’ve no idea why you would, but the options are endless. Make sure to check out awesome-electron for more resources.

Release Flow

What’s it like to maintain and live with a desktop app? First of all, the release flow is completely different. A significant mindset adjustment is required. When you’re working on the web app and you deploy a change that breaks something, it’s not really a huge deal (of course, that depends on your app and the bug). You can just roll out a fix. Users who reload or change the page and new users who trickle in will get the latest code. Developers under pressure might rush out a feature for a deadline and fix bugs as they’re reported or noticed. You can’t do that with desktop apps. You can’t take back updates you push out there. It’s more like a mobile app flow. You build the app, put it out there, and you can’t take it back. Some users might not even update from a buggy version to the fixed version. This will make you worry about all of the bugs out there in old versions.

Quantum Mechanics

Because a host of different versions of your app are in use, your code will exist in multiple forms and states. Multiple variants of your client (desktop app) could be hitting your API in 10 slightly different ways. So, you’ll need to strongly consider versioning your API, really locking down and testing it well. When an API change is to be introduced, you might not be sure if it’s a breaking change or not. A version released a month ago could implode because it has some slightly different code.

Fresh Problems To Solve

You might receive a few strange bug reports — ones that involve bizarre user account arrangements, specific antivirus software or worse. I had a case in which a user had installed something (or had done something themselves) that messed with their system’s environment variables. This broke our app because a dependency we used for something critical failed to execute a system command because the command could no longer be found. This is a good example because there will be occasions when you’ll have to draw a line. This was something critical to our app, so we couldn’t ignore the error, and we couldn’t fix their machine. For users like this, a lot of their desktop apps would be somewhat broken at best. In the end, we decided to show a tailored error screen to the user if this unlikely error were ever to pop up again. It links to a document explaining why it has occurred and has a step-by-step guide to fix it.

Sure, a few web-specific concerns are no longer applicable when you’re working on a desktop app, such as legacy browsers. You will have a few new ones to take into consideration, though. There’s a 256-character limit on file paths in Windows, for example.

Old versions of npm store dependencies in a recursive file structure. Your dependencies would each get stored in their own directory within a node_modules directory in your project (for example, node_modules/a). If any of your dependencies have dependencies of their own, those grandchild dependencies would be stored in a node_modules within that directory (for example, node_modules/a/node_modules/b). Because Node.js and npm encourage small single-purpose modules, you could easily end up with a really long path, like path/to/your/project/node_modules/a/node_modules/b/node_modules/c/…/n/index.js.

Note: Since version 3, npm flattens out the dependency tree as much as possible. However, there are other causes for long paths.

We had a case in which our app wouldn’t launch at all (or would crash soon after launching) on certain versions of Windows due to an exceeding long path. This was a major headache. With Electron, you can put all of your app’s code into an asar archive, which protects against path length issues but has exceptions and can’t always be used.

We created a little Gulp plugin named gulp-path-length, which lets you know whether any dangerously long file paths are in your app. Where your app is stored on the end user’s machine will determine the true length of the path, though. In our case, our installer will install it to C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming. So, when our app is built (locally by us or by a continuous integration service), gulp-path-length is instructed to audit our files as if they’re stored there (on the user’s machine with a long username, to be safe).

var gulp = require('gulp');

var pathLength = require('gulp-path-length');

gulp.task('default', function(){

gulp.src('./example/**/*', {read: false})

.pipe(pathLength({

rewrite: {

match: './example',

replacement: 'C:\\Users\\this-is-a-long-username\\AppData\\Roaming\\Teamwork Chat\\'

}

}));

});

Fatal Errors Can Be Really Fatal

Because all of the automatic updates handling is done within the app, you could have an uncaught exception that crashes the app before it even gets to check for an update. Let’s say you discover the bug and release a new version containing a fix. If the user launches the app, an update would start downloading, and then the app would die. If they were to relaunch app, the update would start downloading again and… crash. So, you’d have to reach out to all of your users and let them know they’ll need to reinstall the app. Trust me, I know. It’s horrible.

Analytics And Bug Reports

You’ll probably want to track usage of the app and any errors that occur. First of all, Google Analytics won’t work (out of the box, at least). You’ll have to find something that doesn’t mind an app that runs on file:// URLs. If you’re using a tool to track errors, make sure to lock down errors by app version if the tool supports release-tracking. For example, if you’re using Sentry to track errors, make sure to set the release property when setting up your client, so that errors will be split up by app version. Otherwise, if you receive a report about an error and roll out a fix, you’ll keep on receiving reports about the error, filling up your reports or logs with false positives. These errors will be coming from people using older versions.

Electron has a crashReporter module, which will send you a report any time the app completely crashes (i.e. the entire app dies, not for any old error thrown). You can also listen for events indicating that your renderer process has become unresponsive.

Security

Be extra-careful when accepting user input or even trusting third-party scripts, because a malicious individual could have a lot of fun with access to Node.js. Also, never accept user input and pass it to a native API or command without proper sanitation.

Don’t trust code from vendors either. We had a problem recently with a third-party snippet we had included in our app for analytics, provided by company X. The team behind it rolled out an update with some dodgy code, thereby introducing a fatal error in our app. When a user launched our app, the snippet grabbed the newest JavaScript from their CDN and ran it. The error thrown prevented anything further from executing. Anyone with the app already running was unaffected, but if they were to quit it and launch it again, they’d have the problem, too. We contacted X’s support team and they promptly rolled out a fix. Our app was fine again once our users restarted it, but it was scary there for a while. We wouldn’t have been able to patch the problem ourselves without forcing affected users to manually download a new version of the app (with the snippet removed).

How can you mitigate this risk? You could try to catch errors, but you’ve no idea what they company X might do in its JavaScript, so you’re better off with something more solid. You could add a level of abstraction. Instead of pointing directly to X’s URL from your <script>, you could use Google Tag Manager or your own API to return either HTML containing the <script> tags or a single JavaScript file containing all of your third-party dependencies somehow. This would enable you to change which snippets get loaded (by tweaking Google Tag Manager or your API endpoint) without having to roll out a new update.

However, if the API no longer returned the analytics snippet, the global variable created by the snippet would still be there in your code, trying to call undefined functions. So, we haven’t solved the problem entirely. Also, this API call would fail if a user launches the app without a connection. You don’t want to restrict your app when offline. Sure, you could use a cached result from the last time the request succeeded, but what if there was a bug in that version? You’re back to the same problem.

Another solution would be to create a hidden window and load a (local) HTML file there that contains all of your third-party snippets. So, any global variables that the snippets create would be scoped to that window. Any errors thrown would be thrown in that window and your main window(s) would be unaffected. If you needed to use those APIs or global variables in your main window(s), you’d do this via IPC now. You’d send an event over IPC to your main process, which would then send it onto the hidden window, and if it was still healthy, it would listen for the event and call the third-party function. That would work.

This brings us back to security. What if someone malicious at company X were to include some dangerous Node.js code in their JavaScript? We’d be rightly screwed. Luckily, Electron has a nice option to disable Node.js for a given window, so it simply wouldn’t run:

// main.js

const {app, BrowserWindow} = require('electron');

let thirdPartyWindow;

app.on('ready', () => {

thirdPartyWindow = new BrowserWindow({

width: 500,

height: 400,

webPreferences: {

nodeIntegration: false

}

});

thirdPartyWindow.loadURL('file://' + __dirname + '/third-party-snippets.html');

});

Automated Testing

NW.js doesn’t have any built-in support for testing. But, again, you have access to Node.js, so it’s technically possible. There is a way to test stuff such as button-clicking within the app using Chrome Remote Interface, but it’s tricky. Even then, you can’t trigger a click on a native window control and test what happens, for example.

The Electron team has created Spectron for automated testing, and it supports testing native controls, managing windows and simulating Electron events. It can even be run in continuous integration builds.

var Application = require('spectron').Application

var assert = require('assert')

describe('application launch', function () {

this.timeout(10000)

beforeEach(function () {

this.app = new Application({

path: '/Applications/MyApp.app/Contents/MacOS/MyApp'

})

return this.app.start()

})

afterEach(function () {

if (this.app && this.app.isRunning()) {

return this.app.stop()

}

})

it('shows an initial window', function () {

return this.app.client.getWindowCount().then(function (count) {

assert.equal(count, 1)

})

})

})

Because your app is HTML, you could easily use any tool to test web apps, just by pointing the tool at your static files. However, in this case, you’d need to make sure the app can run in a web browser without Node.js.

Desktop And Web

It’s not necessarily about desktop or web. As a web developer, you have all of the tools required to make an app for either environment. Why not both? It takes a bit more effort, but it’s worth it. I’ll mention a few related topics and tools, which are complicated in their own right, so I’ll keep just touch on them.

First of all, forget about “browser lock-in,” native WebSockets, etc. The same goes for ES6. You can either revert to writing plain old ES5 JavaScript or use something like Babel to transpile your ES6 into ES5, for web use.

You also have requires throughout your code (for importing other scripts or modules), which a browser won’t understand. Use a module bundler that supports CommonJS (i.e. Node.js-style requires), such as Rollup, webpack or Browserify. When making a build for the web, a module bundler will run over your code, traverse all of the requires and bundle them up into one script for you.

Any code using Node.js or Electron APIs (i.e. to write to disk or integrate with the desktop environment) should not be called when the app is running on the web. You can detect this by checking whether process.version.nwjs or process.versions.electron exists; if it does, then your app is currently running in the desktop environment.

Even then, you’ll be loading a lot of redundant code in the web app. Let’s say you have a require guarded behind a check like if(app.isInDesktop), along with a big chunk of desktop-specific code. Instead of detecting the environment at runtime and setting app.isInDesktop, you could pass true or false into your app as a flag at buildtime (for example, using the envify transform for Browserify). This will aide your module bundler of choice when it’s doing its static analysis and tree-shaking (i.e. dead-code elimination). It will now know whether app.isInDesktop is true. So, if you’re running your web build, it won’t bother going inside that if statement or traversing the require in question.

Continuous Delivery

There’s that release mindset again; it’s challenging. When you’re working on the web, you want to be able to roll out changes frequently. I believe in continually delivering small incremental changes that can be rolled back quickly. Ideally, with enough testing, an intern can push a little tweak to your master branch, resulting in your web app being automatically tested and deployed.

As we covered earlier, you can’t really do this with a desktop app. OK, I guess you technically could if you’re using Electron, because electron-builder can be automated and, so, can spectron tests. I don’t know anyone doing this, and I wouldn’t have enough faith to do it myself. Remember, broken code can’t be taken back, and you could break the update flow. Besides, you don’t want to deliver desktop updates too often anyway. Updates aren’t silent, like they are on the web, so it’s not very nice for the user. Plus, for users on macOS, delta updates aren’t supported, so users would be downloading a full new app for each release, no matter how small a tweak it has.

You’ll have to find a balance. A happy medium might be to release all fixes to the web as soon as possible and release a desktop app weekly or monthly — unless you’re releasing a feature, that is. You don’t want to punish a user because they chose to install your desktop app. Nothing’s worse than seeing a press release for a really cool feature in an app you use, only to realize that you’ll have to wait a while longer than everyone else. You could employ a feature-flags API to roll out features on both platforms at the same time, but that’s a whole separate topic. I first learned of feature flags from “Continuous Delivery: The Dirty Details,” a talk by Etsy’s VP of Engineering, Mike Brittain.

Conclusion

So, there you have it. With minimal effort, you can add “desktop app developer” to your resumé. We’ve looked at creating your first modern desktop app, packaging, distribution, after-sales service and a lot more. Hopefully, despite the pitfalls and horror stories I’ve shared, you’ll agree that it’s not as scary as it seems. You already have what it takes. All you need to do is look over some API documentation. Thanks to a few new powerful APIs at your disposal, you can get the most value from your skills as a web developer. I hope to see you around (in the NW.js or Electron community) soon.

Other Resources

- “Resurrecting Clippy,” Adam Lynch (me) How I built clippy.desktop with NW.js.

- “Essential Electron,” Jessica Lord A plain-speak introduction to Electron and its core concepts.

- Electron Documentation Want to dig into the details? Get it straight from the source.

- “Electron Community” A curated list of Electron-related tools, videos and more.

- “Serverless Crash Reporting for Electron Apps,” Adam Lynch (me) My experience dabbling with serverless architecture, specifically for handling crash reports from Electron apps.

- electron-builder, Stefan Judis The complete solution for packaging and building a ready-for-distribution Electron app, with support for automatic updates (and more) out of the box.

- “autoUpdater,” Electron Documentation See just how simple Electron’s automatic-update API is.

Further Reading

- Pixel-Perfect Specifications Without The Headaches

- Building A First-Class App That Leverages Your Website

- Mobile Considerations in UX Design: “Web or Native?”

- A Beginner’s Guide To Progressive Web Apps