The Surprising Relationship Between Gamification And Modern Persuasion

If you’re like me, then being persuaded requires a scientific approach and concrete examples. And that’s exactly what this article does. It explains how gamification can work by showing the relationship between gamification, UX design and BJ Fogg’s modern persuasion phenomenon, “mass interpersonal persuasion.” And it has a lot of practical gamification examples that you can apply to your own products for more engaging experiences.

Today, virtually all companies (except for special ones like Basecamp) have to grow non-stop. Why? Well, that’s simply how the capitalist engine works. Investors pour money into startups, banks loan money to entrepreneurs, employees accept stock options instead of cash, all in the hope of the company growing much bigger. That’s why there is so much emphasis on growth. Otherwise, the whole system would collapse. It’s kind of crazy when you think a bit more deeply about it, but I’ll leave that part to you for now.

What we call “growth” in the tech world is called “persuasion” in academia. With this article, I want to show why gamification is a great tool for growth and how persuasion science (more precisely, the “mass interpersonal persuasion” phenomenon) proves that. I’ll do that with examples and facts. Let’s get going.

Taking Gamification To Another Level

Not only can gamification help sell your products better, but it can also be used to improve the user experience of your websites and apps. Read more →

Two Misnomers: “User Experience Design” And “Gamification”

I think a lot about words, their meanings and how they shape our perception. This is of special importance to us UX and product people because we’re flooded with jargon. Let’s look at the following example to better understand the importance of words.

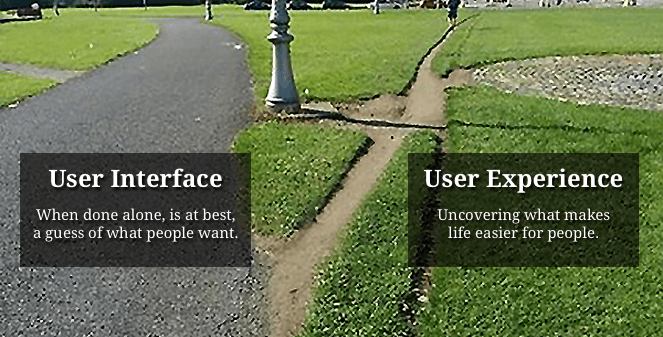

“UX is not UI” is a common reproach, and it is correct. Thanks to this famous photograph above, we now better understand that UX is not UI. But UX — or, more precisely, user experience design — is not usability either, as implied in the photograph. It requires an understanding of business goals as well as user needs and satisfaction of both, in a coherent fashion. But because the term “user experience design” does not imply anything about business, nobody talks about business. Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner in Economics, has a term for this phenomenon: What you see is all there is. We do not see “business” in user experience design, so it becomes all about users.

Gamification is another victim of misnaming. Contrary to popular belief, it does not entail users playing or giving them points. Yes, those are useful components, but not the whole thing. The purpose of gamification is not to make people have fun, either. The purpose is to use fun to motivate people towards certain behaviors. Motivation is the key here. As shown above by Michael Wu, motivation and game components are in parallel. That’s why we use gamification to motivate users. If that parallel were provided by something else — say, biology — then we’d use biologification to motivate users.

So, what is gamification? One of my favorite definitions comes from Juho Hamari of Tampere University of Technology:

"Gamification is a process of enhancing a service with affordances for gameful experiences in order to support user's overall value creation."

My other favorite definition comes from Kevin Werbach of the University of Pennsylvania:

"Gamification is the process of making activities more game-like. In other words, it covers coordinated practices that objectively manifest the intent to produce more of the kinds of experiences that typify games."

As much as I like the definitions above, I still miss the emphasis on motivation and behaviors. So, here goes my definition of gamification:

"Gamification is about using game-like setups to increase user motivation for behaviors that businesses target."

Naturally, my definition resembles user experience design. It does that by mixing the first two definitions. I’ve tried to convey how gamification satisfies users and businesses at the same time. I am not sure which definition is the most accurate, but I know this for sure: We have been playing games since we lived in caves, and we enjoy them for some reason. It’s only sensible to get inspiration from games, be it for business, education or something else.

Persuasion

If we want to understand persuasion, then we should understand, before anything else, that people are predictably irrational. Predictably irrational means that, even though people do not behave rationally most of the time, there are still patterns in this irrationality that help us predict future behaviors. This is why logic alone is not enough to persuade people. If people were consistently rational beings, then we would be living in a completely different world. For example, TV ads would merely consist of logical statements instead of gorgeous video productions. Coca-Cola ads would be like, “Coca Cola > Pepsi,” and Sony’s famous “Like no other” slogan would turn into “Sony !≈ anything else.”

Persuasion requires understanding neurology, psychology, biology, technology… a lot of “-ologies”. But arguably, the most important of all these ologies is technology, thanks to the unprecedented advancements in Internet and mobile in the last decade.

So much so that BJ Fogg said the following (PDF, 208 KB):

"This phenomenon (Mass Interpersonal Persuasion) brings together the power of interpersonal persuasion with the reach of mass media. I believe this new way to change attitudes and behavior is the most significant advance in persuasion since radio was invented in the 1890s."

Bear in mind that, from a scientific point of view, persuasion is an umbrella term for affecting people’s attitudes, behaviors, intentions or beliefs. It does not necessarily require changing people’s beliefs or ideas.

Let me give you an example.

My father, 62 years old, has always been critical of iPhones because he finds the prices unreasonable — not because he cannot afford one, but because an iPhone 7 Plus (256 GB) costs almost four times the minimum wage in Turkey, where we live. But he bought an iPhone 7 for himself last month. How come? Well, for a year or so, he has been telling me how his friends have these big-screen phones and show him pictures of their grandchildren. Eventually, he got fed up with not being able to do the same and bought an iPhone 7. (All he needs now is a grandchild… sigh!) He still finds it expensive, but he bought it anyway. His idea did not change, but his behavior did. That’s what we call persuading without changing beliefs.

Mass Interpersonal Persuasion And Gamification

"In 2007 a new form of persuasion emerged: mass interpersonal persuasion (MIP). The advances in online social networks now allow individuals to change attitudes and behaviors on a mass scale."

This is how BJ Fogg defines MIP. The advances he mentions in the definition start with the launch of Facebook Platform in 2007. Facebook Platform is an aggregation of services and products available to third-party developers so that they can create games, applications and other services using Facebook data. Facebook’s success triggered other platforms to provide similar services. Fast-forward to today: We are living in an era when we type passwords no more, thanks to sign-in with Facebook, Google and Twitter. Or, if we want something more advanced, we can get a personality analysis just by providing our Twitter handle. For an example that’s even more advanced — and scary — we can look at the debates on Facebook’s alleged influence on the latest US elections. This is how powerful social platforms are today.

MIP consist of six components. To better understand MIP and its connection to gamification, let’s look at what they are, one by one, with examples.

1. Persuasive Experience

The following quote (and the remaining ones in this article) is taken from BJ Fogg:

"An experience that is created to change attitudes, behaviors, or both."

The key here is the intentionality to change behaviors or attitudes by providing experiences, as opposed to just stating facts and expecting people to be reasonable enough to change their behaviors or attitudes accordingly.

Now, let’s remember our definition of gamification:

"Gamification is using game-like setups to increase user motivation for behaviors that businesses target."

Similar to MIP, gamification is quite intentional about changing behaviors. It does that by focusing on the entirety of the users’ experience to find the relevant spots where it can blend in the experience and do its magic. A great example of this is Sweden’s Speed Camera Lottery. The Speed Camera Lottery is a simple solution. If you do not drive over the speed limit, then you instantly get a chance to participate in a lottery. Even funnier is that the winnings comes from the fines paid by speeders.

To better understand the intentionality behind behavior change, let’s compare the Speed Camera Lottery with the campaign of New York City’s Department of Transportation (NYC DOT).

Sweden’s Speed Camera Lottery

NYC DOT’s campaign is quite impressive, with its powerful visual and message. “Hit at 40 mph: There’s a 70% chance I’ll die. Hit at 30 mph: There’s an 80% chance I’ll live.” It’s hard to compare these two campaigns because the cultures in these two countries differ quite a lot, and NYC DOT’s campaign encompasses a lot of different initiatives, such as new traffic signals, speed bumps, and pedestrian walkways. However, when viewed from a purely behavioral science point of view, the Speed Camera Lottery is more likely to influence the behavior of obeying the speed limit. Why?

- The NYC campaign favors an indirect way of influencing behavior. It’s very influential when we see it, but it is not there when we actually need to slow down. Unlike the NYC DOT ad, the lottery solution is implemented right when and where speeding happens.

- NYC DOT’s campaign does not create an experience. It’s an example of a classic one-way communication. You see it and it’s gone. With the Speed Camera Lottery, we get a chance to participate and, thus, have an experience.

- The Speed Camera Lottery is more fun than the NYC DOT’s campaign because the former is a well-gamified campaign and the latter is basically an informative ad.

That being said, though highly successful (reducing the average speed by 22%), the Speed Camera Lottery had one downside. Some geniuses started circling around to increase their likelihood of winning the lottery. Well, that did not quite work out for them, but we should always be wary of cheaters.

2. Automated Structure

"Digital technology structures the persuasive experience."

We saw how the core of gamification is to create persuasive experiences with the first component of MIP. Now let’s look at the link between gamification and automated structures.

By design, gamification produces well-structured processes. Regardless of what product we are building, we need a tool to quantify behaviors to even start with gamification. Think of something similar to Google Analytics or MixPanel. For behavior tracking to be useful, we do not just count how many people perform a certain behavior, but rather define rules like, “If a user clicks five help links in a session, then open the chat window.” Gamification, by nature, is built on top of these kinds of rules:

- Automated feedback: “If a user logs in for five consecutive days, then show them a message to congratulate them on their consistency.”

- Points: “If a user invites a friend, then reward them with 5 points.”

- Levels: “If a user collects 1000 points and receives 5 likes, then bump them up to level 3.”

We could easily add more examples to the list. Obviously, these are very simple examples, but the point is that gamification is inherently based on rules. That’s why it is very easy to build an automated structure to create a persuasive experience using gamification.

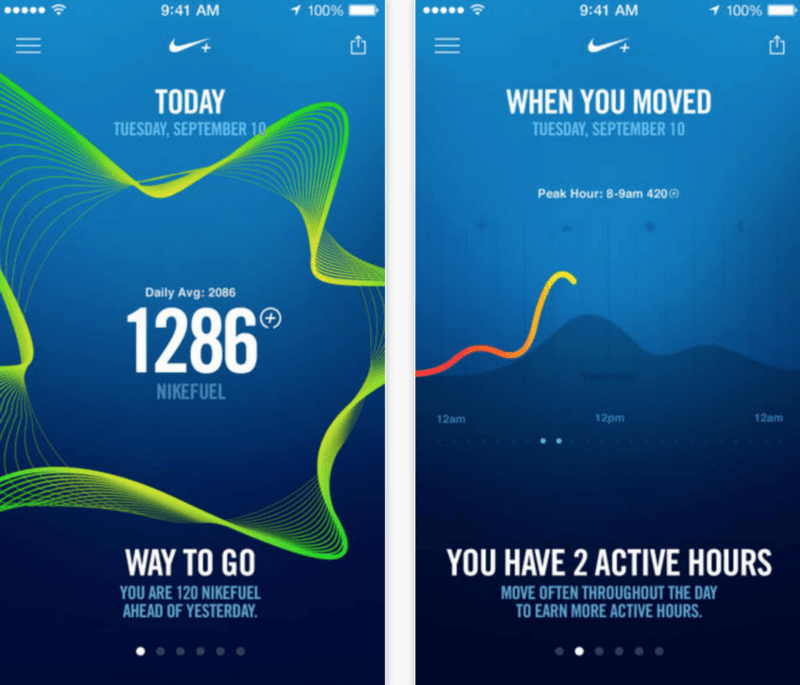

Example: Nike Fuel

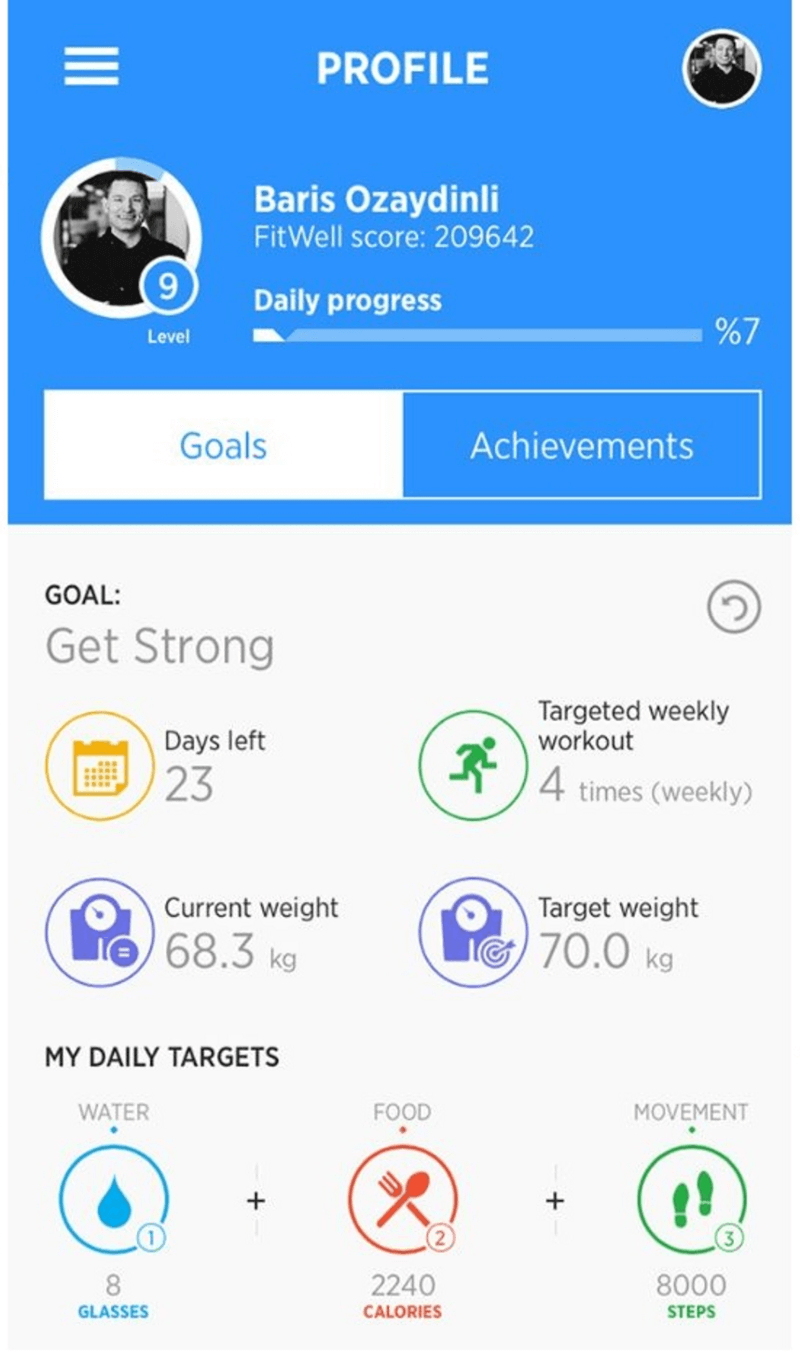

I did gamification design for FitWell, an app that tailors meal plans and workout regimens according to the app’s assessment. Our research showed that the most important problem people encounter during their fitness journey is that they lack feedback after a while. At the beginning, we feel energized, see changes in our posture and, thus, feel motivated. After a while, though, progress slows, and we start worrying that our efforts are accomplishing nothing. That’s where gamification comes into play. With a lot of automated feedback loops, users get various encouraging feedback when their body fails to provide any.

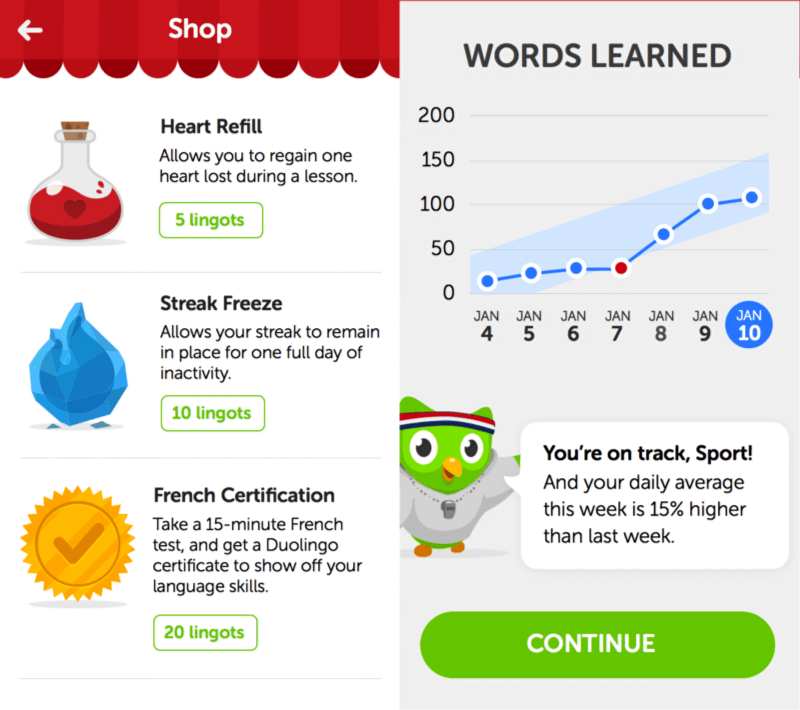

Example: Duolingo

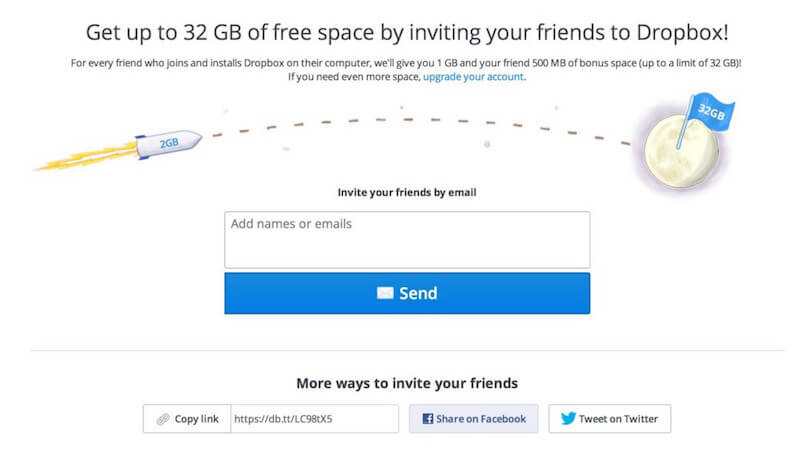

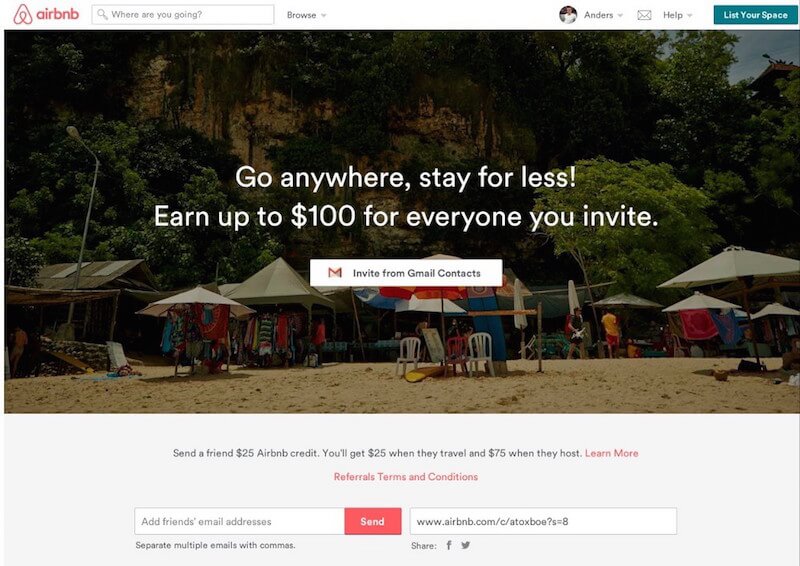

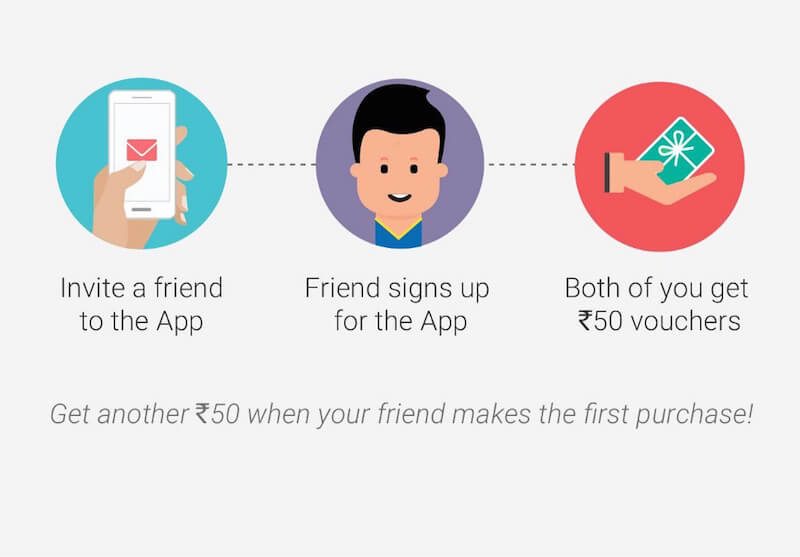

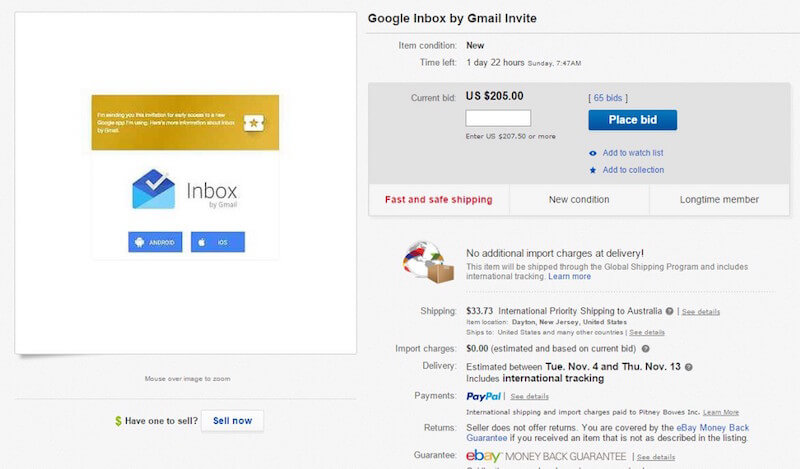

"The persuasive experience is shared from one friend to another."We just saw how gamification helps us with automating persuasive experiences. Now let's see how gamification fuels social distribution. Just four words: "Invite friends, earn money!" Money here is a variable. It could be anything from free disk space to an invitation to that new cool app. The key here is that it always involves friends and some kind of reward. Example: Dropbox

"What this means is that the time between invitation, acceptance, and a subsequent invitation needs to be small."On a more abstract level, rapid cycle can be restated as follows:

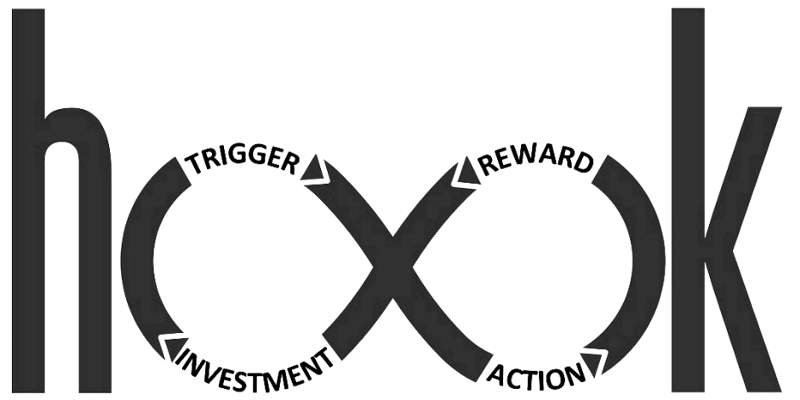

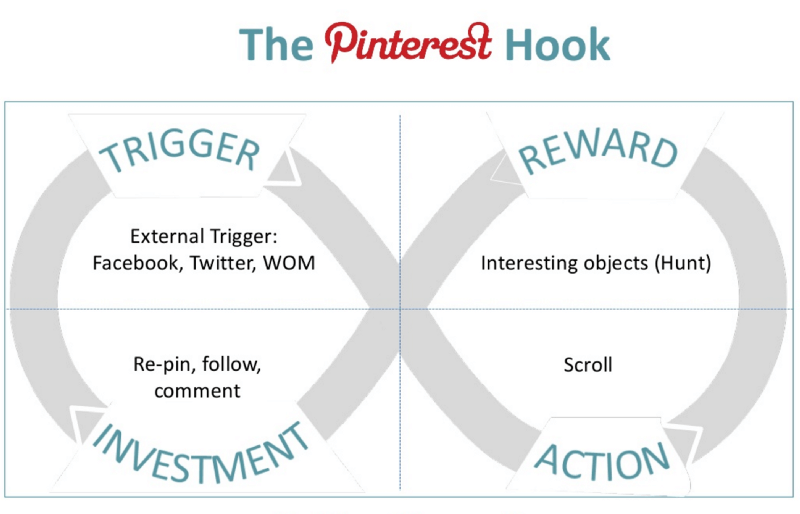

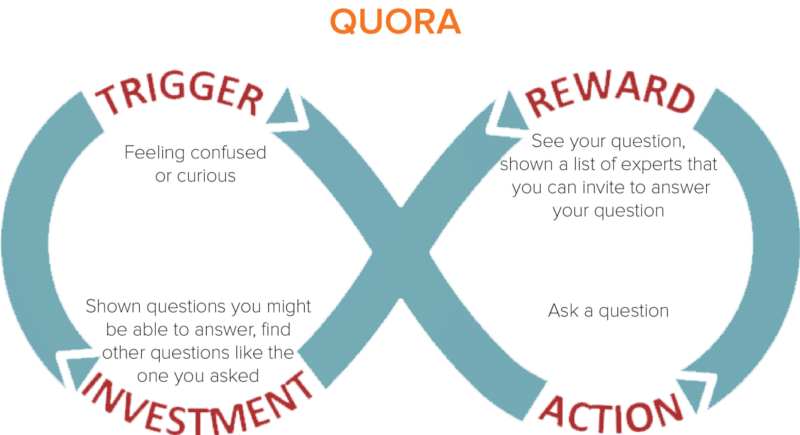

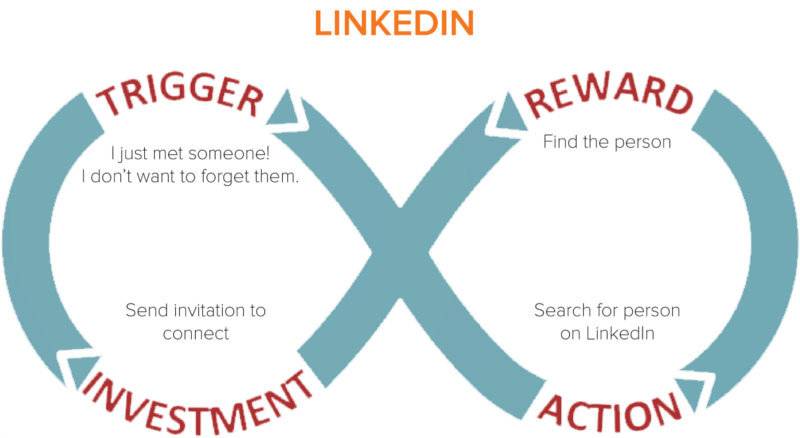

"What this means is that the time between action, feedback, and a subsequent action needs to be small."When viewed like this, Nir Eyal's hook model, the most important tool in my gamification toolbox, perfectly matches rapid cycle. ‘Hook’ is Nir's explanation for why some products are so habit forming. Simply put, we get motivated if we get positive and instant feedback for our behaviors. Even better, if we get a chance to take a further step, we get even more motivated.

- Hook has its roots — surprise, surprise — in BJ Fogg's behavior model, which explains how behavior occurs. BJ Fogg shows that we need a trigger, motivation, and ability to perform a behavior.

- On top of Fogg's behavior model, Nir Eyal adds a variable reward, so that people keep coming for more.

- And Eyal asks for an investment behavior, which increases the user's expectation of even more rewards in the future.

(RJ Metrics Blog, Janessa Lantz)

5. Huge Social Graph

"The persuasive experience can potentially reach millions of people connected through social ties or structured interactions."

Having millions of users is not enough for MIP to happen. What you need is millions of connected people, and the nice part is that they do not have to be your users either. You need the potential to reach millions. How? Well, for one, there are social networks. Use social log-in and leverage your users’ networks on those platforms. But that is not the only way. Suppose you have a SaaS analytics product. How can you reach millions? Provide Google Analytics integration and voilà! Now you’re relevant to millions of people.

Let’s look at how gamification helps connect people.

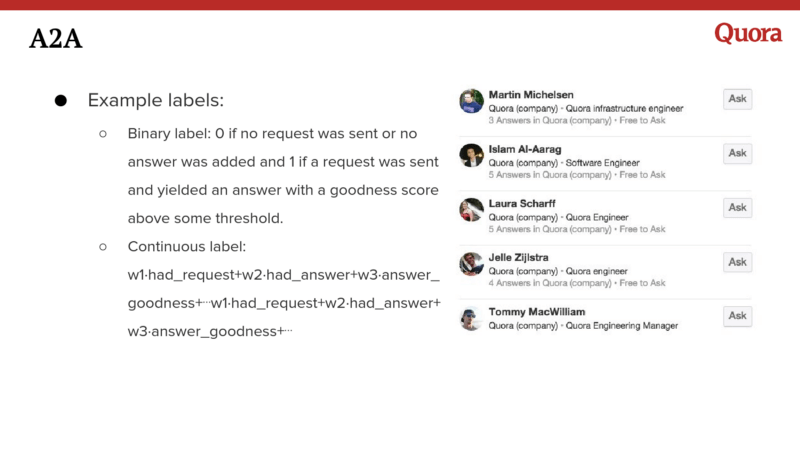

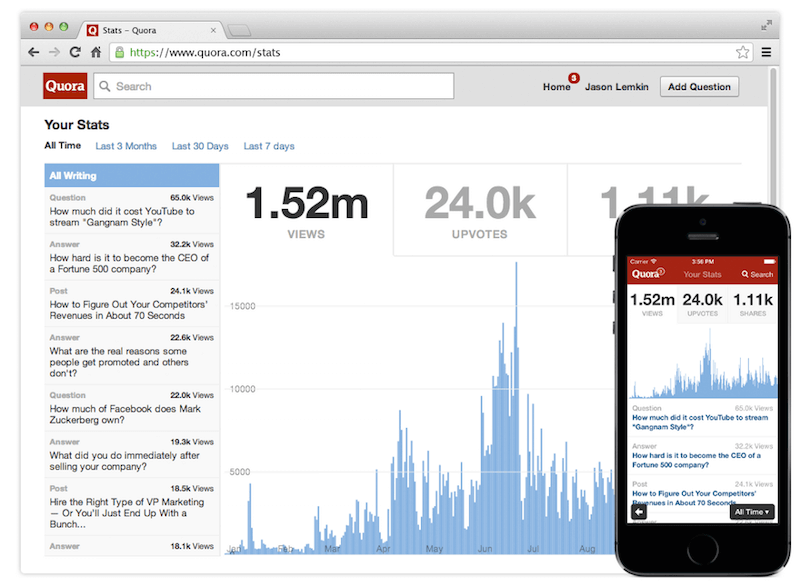

Example: Quora

Quora’s “Ask to Answer”

Quora suggests people with related expertise when we ask a question. This is an amazing solution. Why?

- It helps us get answers much faster and from reliable sources.

- It honors people who get asked to answer, which gets them motivated and engaged. (A common phrase on Quora is, “Thank you for A2A.”)

- The combination of points 1 and 2 increases high-quality content, engagement and connectedness on Quora.

And this is all possible thanks to a very simple game mechanic: mastery. None of this would work if Quora did not have those domain experts.

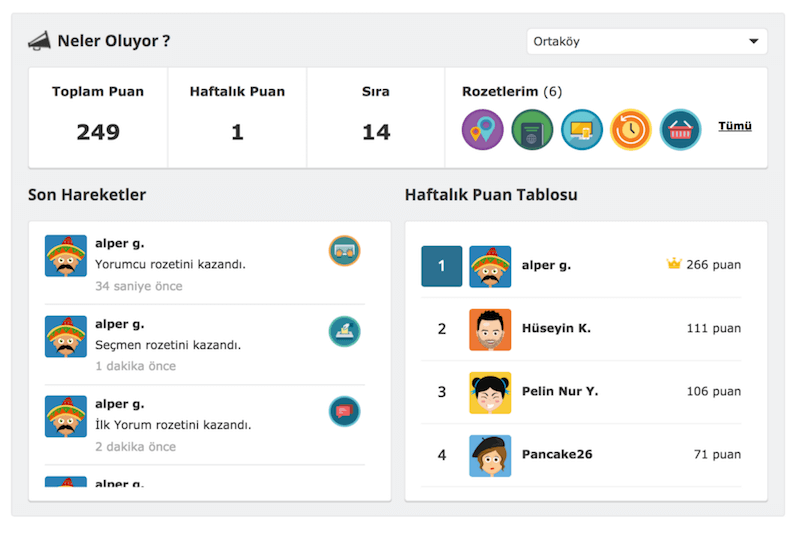

Example: Yemeksepeti

This example is from my hometown — hence, the language in the photo. Yemeksepeti is the Turkish version of Delivery Hero. They recently introduced a “muhtar” feature. Muhtar means “headman” in Turkish. A muhtar knows everyone and every detail about a neighborhood. So, the one with the most points in a neighborhood becomes the muhtar. As you can see, Alper G. is the muhtar in my neighborhood (the list on the right is the leaderboard).

I’ve been using Yemeksepeti for more than five years, and this is the first time I’ve been more curious about the people using it than about the restaurants on Yemeksepeti. The reason is the muhtars. Not only does it show who a neighbourhood’s muhtar is, but it also shows their recent orders and what other participants are doing on Yemeksepeti. The muhtar feature provides the basic social-proof mechanism that Yemeksepeti needed. It helps greatly with making faster decisions and increases the credibility of the restaurants’ scores. (People score a restaurant after a delivery, similar to scoring an Uber driver.)

The Muhtar feature also paves the way for Yemeksepeti to introduce its own version of A2A. I don’t know if they plan to do this (although it’s one of the ideas we presented to them four years ago), but they could surface experts who help others answer the toughest of all questions: “What should I eat?”

That’s the power of gamification. By introducing competition (or collaboration, as we saw with Quora), it makes socialization possible on a very large scale without people actually having to know each other.

6. Measurable Impact

"The effect of the persuasive experience is observable by users and creators."

One of the core components of gamification is quantification of what users do and of the things happening around them. This way, gamification makes everything measurable by nature. Even the tiniest of behaviors are quantified and presented in various ways, sometimes as raw data, other times as points, levels or progress bars. Let’s look at some examples.

Example: Twitter

Everything, including followers, moments, likes and retweets, is quantified and put front and center.

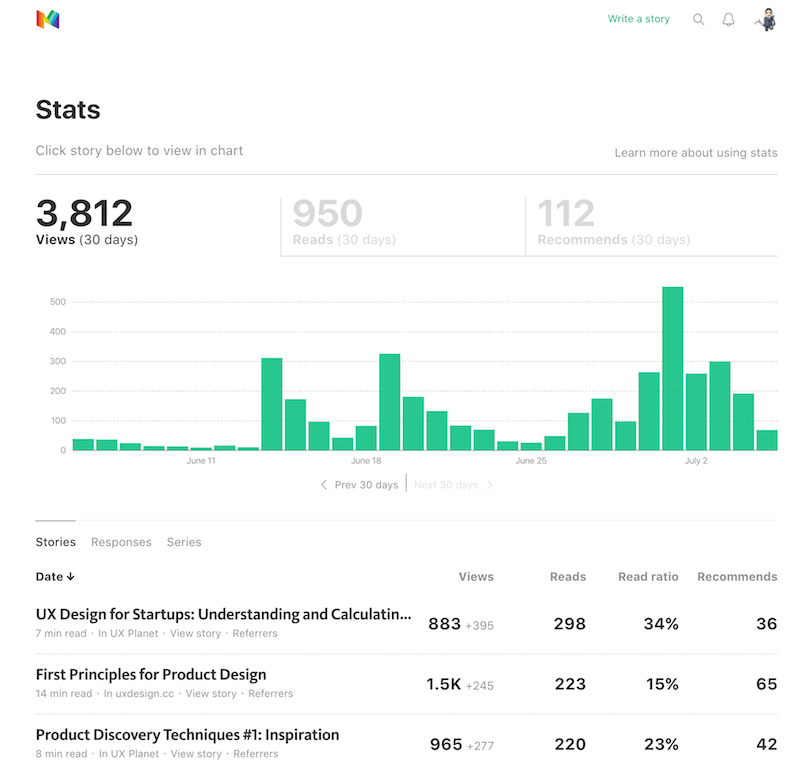

Example: Quora and Medium

Medium and Quora are very different in how people create content, but in the end, it is content they create. That’s why it is not surprising to see that almost identical statistics are provided.

Summary

- Similar to MIP’s persuasive experience component, good gamification always directly targets behaviors and blends in the experience.

- MIP relies on automated structures, and gamification relies on behavior-based rules, which makes it extremely easy to build automated structures.

- MIP requires social distribution, and gamification responds to this with a killer feature: Invite friends and earn money, disk space, beta participation etc. This is an old gamification practice and a powerful social-distribution tool. And you do not always have to give away “stuff.” Giving away status works, too.

- Rapid cycles are at the heart of MIP. They are at the core of gamification, too, as shown by Nir Eyal’s hook model. People get motivated when the feedback for their behavior is instant. To take it a step further, try to make the feedback variable and the next step obvious.

- Another important component of MIP is a huge social graph. Collaboration and competition mechanics make it easy to connect people to each other, even on the least likely of platforms.

- Lastly, MIP requires people to be able to measure the impact of their behaviors. Gamification inherently requires measuring almost everything, which makes it extremely easy to make visible at all times.

- Gamification aims to use fun in order to motivate users towards behaviors that businesses target. This approach satisfies both the user and the behavior, which is essential to good user experience design.

Conclusion

One by one, we saw how the six components of mass interpersonal persuasion relate to gamification, with examples. I chose well-known examples so that they would be easier to understand and relate to. However, I realize that this makes gamification design intimidating. You might be thinking, “Of course, Quora would do that — they have all of these great designers,” or, “Obviously, Nike would succeed — they have all of those technologies and tools”. Perhaps also, “What does MIP have to do with growth?”. Take a look at this:

Let’s go back to the fall of 2007 — a time when there was no WhatsApp, Instagram or Snapchat, when Twitter was a one-year-old baby, when Facebook announced its Platform. When BJ Fogg heard about Platform, he decided to start a new course to apply MIP principles to Facebook and measure the impact of the application of those principles. Grading was based on metrics on the Platform. There was no homework or quizzes. Students were graded based on the number of users they’ve reached and engaged through the apps they’ve built.

The numbers shown in the image above are the results of that course. The students, some of whom had no experience in coding, design or digital marketing, reached 16 million users in 10 weeks. And this happened in 2007. 2007 is the year when the first iPhone was unveiled. Think about it: Some of those apps generated so much revenue (more than $1 million in three months) that even the teaching assistant, Dan Ackerman, dropped out of school. Five of those apps made it to the top-100 apps on Facebook and reached more than 1 million users each.

So, if those students were able to design such successful experiences, why couldn’t you?

Further Reading

- The UX Of Flight Searches: How We Challenged Industry Standards

- Better Context Menus With Safe Triangles

- Creating Accessible UI Animations

- How To Design Powerful Narratives On Mobile