Learning Elm From A Drum Sequencer (Part 2)

In part one of this two-part article, we began building a drum sequencer in Elm. We learned the syntax, how to read and write type-annotations to ensure our functions can interact with one another, and the Elm Architecture, the pattern in which all Elm programs are designed.

In this conclusion, we’ll work through large refactors by relying on the Elm compiler, and set up recurring events that interact with JavaScript to trigger drum samples.

Check out the final code here, and try out the project here. Let’s jump to our first refactor!

Refactoring With The Elm Compiler

The thought of AI taking over developer jobs is actually pleasant for me. Rather than worry, I’ll have less to program, I imagine delegating the difficult and boring tasks to the AI. And this is how I think about the Elm Compiler.

The Elm Compiler is my expert pair-programmer who’s got my back. It makes suggestions when I have typos. It saves me from potential runtime errors. It leads the way when I’m deep and lost midway through a large refactor. It confirms when my refactor is completed.

Refactoring Our Views

We’re going to rely on the Elm Compiler to lead us through refactoring our model from track : Track to tracks : Array Track. In JavaScript, a big refactor like this would be quite risky. We’d need to write unit tests to ensure we’re passing the correct params to our functions then search through the code for any references to old code. Fingers-crossed, we’d catch everything, and our code would work. In Elm, the compiler catches all of that for us. Let’s change our type and let the compiler guide the way.

The first error says our model doesn’t contain track and suggests we meant tracks, so let’s dive into View.elm. Our view function calling model.track has two errors:

Trackshould beTracks.- And

renderTrackaccepts a single track, but now tracks are an array of tracks.

We need to map over our array of tracks in order to pass a single track to renderTrack. We also need to pass the track index to our view functions in order to make updates on the correct one. Similar to renderSequence, Array.indexedMap does this for us.

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div []

(Array.toList <| Array.indexedMap renderTrack model.tracks)

We expect another error to emerge because we’re now passing an index to renderTrack, but it doesn’t accept an index yet. We need to pass this index all the way down to ToggleStep so it can be passed to our update function.

renderTrack.Array.indexedMap always passes the index as its first value. We change renderTrack’s type annotation to accept an Int, for the track index, as its first argument. We also add it to the arguments before the equal sign. Now we can use trackIndex in our function to pass it to renderSequence.

renderTrack : Int -> Track -> Html Msg

renderTrack trackIndex track =

div [ class "track" ]

[ p [] [ text track.name ]

, div [ class "track-sequence" ] (renderSequence trackIndex track.sequence)

]

We need to update the type annotation for renderSequence in the same way. We also need to pass the track index to renderStep. Since Array.indexedMap only accepts two arguments, the function to apply and the array to apply the function to, we need to contain our additional argument with parentheses. If we wrote our code without parentheses, Array.indexedMap renderStep trackIndex sequence, the compiler wouldn’t know if trackIndex should be bundled with sequence or with renderStep. Furthermore, it would be more difficult for a reader of the code to know where trackIndex was being applied, or if Array.indexedMap actually took four arguments.

renderSequence : Int -> Array Step -> List (Html Msg)

renderSequence trackIndex sequence =

Array.indexedMap (renderStep trackIndex) sequence

|> Array.toList

Finally, we’ve passed our track index down to renderStep. We add the index as the first argument then add it to our ToggleStep message in order to pass it to the update function.

renderStep : Int -> Int -> Step -> Html Msg

renderStep trackIndex stepIndex step =

let

classes =

if step == Off then

"step"

else

"step _active"

in

button

[ onClick (ToggleStep trackIndex stepIndex step)

, class classes

]

[]

Refactoring Our Update Functions

Considering incorrect arguments, the compiler has found two new errors regarding ToggleStep.

We’ve added trackIndex to it, but haven’t updated it for the track index. Let’s do that now. We need to add it in as an Int.

type Msg

= ToggleStep Int Int Step

Our next batch of errors are in the Update function.

First, we don’t have the right number of arguments for ToggleStep since we’ve added the track index. Next, we are still calling model.track, which no longer exists. Let’s think about a data model for a moment:

model = {

tracks: [

{

name: "Kick",

clip: "kick.mp3",

sequence: [On, Off, Off, Off, On, etc...]

},

{

name: "Snare",

clip: "snare.mp3",

sequence: [Off, Off, Off, Off, On, etc...]

},

etc...

]

etc...

}

In order to update a sequence, we need to traverse through the Model record, the tracks array, the track record, and finally, the track sequence. In JavaScript, this could look something like model.tracks[0].sequence[0], which has several spots for failure. Updating nested data can be tricky in Elm because we need to cover all cases; when it finds what it expects and when it doesn’t.

Some functions, like Array.set handle it automatically by either returning the same array if it can’t find the index or a new, updated array if it does. This is the kind of functionality we’d like because our tracks and sequences are constant, but we can’t use set because of our nested structure. Since everything in Elm is a function, we write a custom helper function that works just like set, but for nested data.

This helper function should take an index, a function to apply if it finds something at the index value, and the array to check. It either returns the same array or a new array.

setNestedArray : Int -> (a -> a) -> Array a -> Array a

setNestedArray index setFn array =

case Array.get index array of

Nothing ->

array

Just a ->

Array.set index (setFn a) array

In Elm a means anything. Our type annotation reads setNestedArray accepts an index, a function that returns a function, the array to check, and it returns an array. The Array a annotation means we can use this general purpose function on arrays of anything. We run a case statement on Array.get. If we can’t find anything at the index we pass, return the same array back. If we do, we use set and pass the function we want to apply into the array.

As our let...in block is about to become large under the ToggleStep branch, we can move the local functions into their own private functions, keeping the update branches more readable. We create updateTrackStep which will utilize setNestedArray to dig into our nested data. It will take: a track index, to find the specific track; a step index, to find which step on the track sequence was toggled; all of the model tracks; and return updated model tracks.

updateTrackStep : Int -> Int -> Array Track -> Array Track

updateTrackStep trackIndex stepIndex tracks =

let

toggleStep step =

if step == Off then

On

else

Off

newSequence track =

setNestedArray stepIndex toggleStep track.sequence

newTrack track =

{ track | sequence = (newSequence track) }

in

setNestedArray trackIndex newTrack tracks

We still use toggleStep to return the new state, newSequence to return the new sequence, and newTrack to return the new track. We utilized setNestedArrayto easily set the sequence and the tracks. That leaves our update function short and sweet, with a single call to updateTrackStep.

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

case msg of

ToggleStep trackIndex stepIndex step ->

( { model | tracks = updateTrackStep trackIndex stepIndex model.tracks }

, Cmd.none

)

From right to left, we pass our array of tracks on model.tracks, the index of the specific step to toggle, and the index of the track the step is on. Our function finds the track from the track index within model.tracks, finds the step within the track’s sequence, and finally toggles the value. If we pass an track index that doesn’t exist, we return the same set of tracks back. Likewise, if we pass a step index that doesn’t exist, we return the same sequence back to the track. This protects us from unexpected runtime failures, and is the way updates must be done in Elm. We must cover all branches or cases.

Refactoring Our Initializers

Our last error lies in Main.elm because our initializers are now misconfigured.

We’re still passing a single track rather than an array of tracks. Let’s create initializer functions for our tracks and an initializer for the track sequences. The track initializers are functions with assigned values for the track record. We have a track for the hi-hat, kick drum, and snare drum, that have all their steps set to Off.

initSequence : Array Step

initSequence =

Array.initialize 16 (always Off)

initHat : Track

initHat =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Hat"

}

initSnare : Track

initSnare =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Snare"

}

initKick : Track

initKick =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Kick"

}

To load these to our main init function, we create an array from the list of initializers, Array.fromList [ initHat, initSnare, initKick ], and assign it to the model’s tracks.

init : ( Model, Cmd.Cmd Msg )

init =

( { tracks = Array.fromList [ initHat, initSnare, initKick ]

}

, Cmd.none

)

With that, we’ve changed our entire model. And it works! The compiler has guided us through the code, so we don’t need to find references ourself. It’s tough not lusting after the Elm Compiler in other languages once you’ve finished refactoring in Elm. That feeling of confidence once the errors are cleared because everything simply works is incredibly liberating. And the task-based approach of working through errors is so much better than worrying about covering all the application’s edge cases.

Handling Recurring Events Using Subscriptions

Subscriptions is how Elm listens for recurring events. These events include things like keyboard or mouse input, websockets, and timers. We’ll be using subscriptions to toggle playback in our sequencer. We’ll need to:

- Prepare our application to handle subscriptions by adding to our model

- Import the Elm time library

- Create a subscription function

- Trigger updates from the subscription

- Toggle our subscription playback state

- And render changes in our views

Preparing Our App For Subscriptions

Before we jump into our subscription function, we need to prepare our application for dealing with time. First, we need to import the Time module for dealing with time.

import Time exposing (..)

Second, we need to add fields to our model handling time. Remember when we modeled our data we relied on playback, playbackPosition, and bpm? We need to re-add these fields.

type alias Model =

{ tracks : Array Track

, playback : Playback

, playbackPosition : PlaybackPosition

, bpm : Int

}

type Playback

= Playing

| Stopped

type alias PlaybackPosition =

Int

Finally, we need to update our init function because we’ve added additional fields to the model. playback should start Stopped, the playbackPosition should be at the end of the sequence length, so it starts at 0 when we press play, and we need to set the beat for bpm.

init : ( Model, Cmd.Cmd Msg )

init =

( { tracks = Array.fromList [ initHat, initSnare, initKick ]

, playback = Stopped

, playbackPosition = 16

, bpm = 108

}

, Cmd.none

)

Subscribing To Time-Based Events In Elm

We’re ready to handle subscriptions. Let’s start by creating a new file, Subscriptions.elm, creating a subscription function, and importing it into the Main module to assign to our Main program. Our subscription function used to return always Sub.none, meaning there would never be any events we subscribed to, but we now want to subscribe to events during playback. Our subscription function will either return nothing, Sub.none, or update the playback position one step at a time, according to the BPM.

main : Program Never Model Msg

main =

Html.program

{ view = view

, update = update

, subscriptions = subscriptions

, init = init

}

subscriptions : Model -> Sub Msg

subscriptions model =

if model.playback == Playing then

Time.every (bpmToMilliseconds model.bpm) UpdatePlaybackPosition

else

Sub.none

During playback, we use Time.every to send a message, UpdatePlaybackPosition to our update function to increment the playback position. Time.every takes a millisecond value as its first argument, so we need to convert BPM, an integer, to milliseconds. Our helper function, bpmToMilliseconds takes the BPM and does the conversion.

bpmToMilliseconds : Int -> Float

bpmToMilliseconds bpm =

let

secondsPerMinute =

Time.minute / Time.second

millisecondsPerSecond =

Time.second

beats =

4

in

((secondsPerMinute / (toFloat bpm) * millisecondsPerSecond) / beats)

Our function is pretty simple. With hard-coded values it would look like (60 / 108 * 1000) / 4. We use a let...in block for readability to assign millisecond values to our calculation. Our function first converts our BPM integer, 108, to a float, divides the BPM by secondsPerMinute, which is 60, multiplies it by the number of milliseconds in a second, 1000, and divides it by the number of beats in our time signature, 4.

We’ve called UpdatePlaybackPostion, but we haven’t used it yet. We need to add it to our message type. Time functions return a time result, so we need to include Time to the end of our message, though we don’t really care about using it.

type Msg

= ToggleStep Int Int Step

| UpdatePlaybackPosition Time

With our subscription function created, we need to handle the missing branch in our update function. This is straightforward: increment the playbackPosition by 1 until it hits the 16th step (15 in the zero-based array).

UpdatePlaybackPosition _ ->

let

newPosition =

if model.playbackPosition >= 15 then

0

else

model.playbackPosition + 1

in

( { model | playbackPosition = newPosition }, Cmd.none )

You’ll notice rather than passing the Time argument into our update branch we’ve used an underscore. In Elm, this signifies there are additional arguments, but we don’t care about them. Our model update is significantly easier here since we’re not dealing with nested data as well. At this point, we’re still not using side-effects, so we use Cmd.none.

Toggling Our Playback State

We can now increment our playback position, but there is nothing to switch the model from Stopped to Playing. We need a message to toggle playback as well as a views to trigger the message and an indicator for which step is being played. Let’s start with the messages.

StartPlayback ->

( { model | playback = Playing }, Cmd.none )

StopPlayback ->

( { model

| playback = Stopped

, playbackPosition = 16

}

, Cmd.none

)

StartPlayback simply switches playback to Playing, whereas StopPlayback switches it and resets the playback position. We can take an opportunity to make our code more followable by turning 16 into a constant and using it where appropriate. In Elm, everything is a function, so constants look no different. Then, we can replace our magic numbers with initPlaybackPosition in StopPlayback and in init.

initPlaybackPosition : Int

initPlaybackPosition =

16

With our messages set, we can now focus on our view functions. It’s common to set playback buttons next to the BPM display, so we’ll do the same. Currently, our view function only renders our tracks. Let’s rename view to renderTracks so it can be a function we call from the parent view.

renderTracks : Model -> Html Msg

renderTracks model =

div [] (Array.toList <| Array.indexedMap renderTrack model.tracks)

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div [ class "step-sequencer" ]

[ renderTracks model

, div

[ class "control-panel" ]

[ renderPlaybackControls model

]

]

Now, we create our main view which can call our smaller view functions. Give our main div a class, step-sequencer, call renderTracks, and create a div for our control panel which contains the playback controls. While we could keep all these functions in the same view, especially since they have the same type annotation, I find breaking functions into smaller pieces helps me focus on one piece at a time. Restructuring, later on, is a much easier diff to read as well. I think of these smaller view functions like partials.

renderPlaybackControls will take our entire model and return HTML. This will be a div that wraps two additional functions. One to render our button, renderPlaybackButton, and one that renders the BPM display, renderBPM. Both of these will accept the model since the attributes are on the top-level of the model.

renderPlaybackControls : Model -> Html Msg

renderPlaybackControls model =

div [ class "playback-controls" ]

[ renderPlaybackButton model

, renderBPM model

]

Our BPM display only shows numbers, and eventually, we want users to be able to change them. For semantics, we should render the display as an input with a number type. Some attributes (like type) are reserved in Elm. When dealing with attributes, these special cases have a trailing underscore. We’ll leave it for now, but later we can add a message to the on change event for the input to allow users to update the BPM.

renderBPM : Model -> Html Msg

renderBPM model =

input

[ class "bpm-input"

, value (toString model.bpm)

, maxlength 3

, type_ "number"

, Html.Attributes.min "60"

, Html.Attributes.max "300"

]

[]

Our playback button will toggle between the two playback states: Playing and Stopped.

renderPlaybackButton : Model -> Html Msg

renderPlaybackButton model =

let

togglePlayback =

if model.playback == Stopped then

StartPlayback

else

StopPlayback

buttonClasses =

if model.playback == Playing then

"playback-button _playing"

else

"playback-button _stopped"

in

button

[ onClick togglePlayback

, class buttonClasses

]

[]

We use a local function, togglePlayback, to attach the correct message to the button’s on click event, and another function to assign the correct visual classes. Our application toggles the playback state, but we don’t yet have an indicator of its position.

Connecting Our Views And Subscriptions

It’s best to use real data to get the length of our indicator rather than a magic number. We could get it from the track sequence, but that requires reaching into our nested structure. We intend to add a reduction of the on steps in PlaybackSequence, which is on the top-level of the model, so that’s easier. To use it, we need to add it to our model and initialize it.

import Set exposing (..)

type alias Model =

{ tracks : Array Track

, playback : Playback

, playbackPosition : PlaybackPosition

, bpm : Int

, playbackSequence : Array (Set Clip)

}

init : ( Model, Cmd.Cmd Msg )

init =

( { tracks = Array.fromList [ initHat, initSnare, initKick ]

, playback = Stopped

, playbackPosition = initPlaybackPosition

, bpm = 108

, playbackSequence = Array.initialize 16 (always Set.empty)

}

, Cmd.none

)

Since a Set forces uniqueness in the collection, we use it for our playback sequence. That way we won’t need to check if the value already exists before we pass it to JavaScript. We import Set and assign playbackSequence to an array of sets of clips. To initialize it we use Array.initialize, pass it the length of the array, 16, and create an empty set.

Onto our view functions. Our indicator should render a series of HTML list items. It should light up when the playback position and the indicator position are equal, and be dim otherwise.

renderCursorPoint : Model -> Int -> Set String -> Html Msg

renderCursorPoint model index _ =

let

activeClass =

if model.playbackPosition == index && model.playback == Playing then

"_active"

else

""

in

li [ class activeClass ] []

renderCursor : Model -> Html Msg

renderCursor model =

ul

[ class "cursor" ]

(Array.toList <| Array.indexedMap (renderCursorPoint model) model.playbackSequence)

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div [ class "step-sequencer" ]

[ renderCursor model

, renderTracks model

, div

[ class "control-panel" ]

[ renderPlaybackControls model

]

]

In renderCursor we use an indexed map to render a cursor point for each item in the playback sequence. renderCursorPoint takes our model to determine whether the point should be active, the index of the point to compare with the playback position, and the set of steps which we aren’t actually interested in. We need to call renderCursor in our view as well.

With our cursor in place, we can now see the effects of our subscription. The indicator lights up on each step as the subscription sends a message to update the playback position, and we see the cursor moving forward.

While we could handle time using JavaScript intervals, using subscriptions seamlessly plugs into the Elm runtime. We maintain all the benefits of Elm, plus we get some additional helpers and don’t need to worry about garbage collection or state divergence. Further, it builds on familiar patterns in the Elm Architecture.

Interacting With JavaScript In Elm

Adoption of Elm would be much more difficult if the community was forced to ignore all JavaScript libraries and/or rewrite everything in Elm. But to maintain its no runtime errors guarantee, it requires types and the compiler, something JavaScript can’t interact with. Luckily, Elm exposes ports as a way to pass data back and forth to JavaScript and still maintain type safety within. Because we need to cover all cases in Elm, if for an undefined reason, JavaScript returns the wrong type to Elm, our program can correctly deal with the error instead of crashing.

We’ll be using the HowlerJS library to easily work with the web audio API. We need to do a few things in preparation for handling sounds in JavaScript. First, handle creating our playback sequence.

Using The Compiler To Add To Our Model

Each track should have a clip, which will map to a key in a JavaScript object. The kick track should have a kick clip, the snare track a snare clip, and the hi-hat track a hat clip. Once we add it to the Track type, we can lean on the compiler to find the rest of the missing spots in the initializer functions.

type alias Track =

{ name : String

, sequence : Array Step

, clip : Clip

}

initHat : Track

initHat =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Hat"

, clip = "hat"

}

initSnare : Track

initSnare =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Snare"

, clip = "snare"

}

initKick : Track

initKick =

{ sequence = initSequence

, name = "Kick"

, clip = "kick"

}

The best time to add or remove these clips to the playback sequence is when we toggle steps on or off. In ToggleStep we pass the step, but we should also pass the clip. We need to update renderTrack, renderSequence, and renderStep to pass it through. We can rely on the compiler again and work our way backward. Update ToggleStep to take the track clip and we can follow the compiler through a series of “not enough arguments.”

type Msg

= ToggleStep Int Clip Int Step

Our first error is the missing argument in the update function, where ToggleStep is missing the trackClip. At this point, we pass it in but don’t do anything with it.

ToggleStep trackIndex trackClip stepIndex step ->

( { model | tracks = updateTrackStep trackIndex stepIndex model.tracks }

, Cmd.none

)

Next, renderStep is missing arguments to pass the clip to ToggleStep. We need to add the clip to our on click event, and we need to allow renderStep to accept a clip.

renderStep : Int -> Clip -> Int -> Step -> Html Msg

renderStep trackIndex trackClip stepIndex step =

let

classes =

if step == On then

"step _active"

else

"step"

in

button

[ onClick (ToggleStep trackIndex trackClip stepIndex step)

, class classes

]

[]

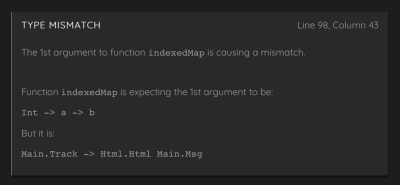

When I was new to Elm, I found the next error challenging to understand. We know it’s a mismatch to Array.indexedMap, but what does a and b mean in Int -> a -> b and why is it expecting three arguments when we’re already passing four? Remember a means anything, including any function. b is similar, but it means anything that’s not a. Likewise, we could see a function that transforms values three times represented as a -> b -> c.

We can break down the arguments when we consider what we pass to Array.indexedMap.

Array.indexedMap (renderStep trackIndex) sequence

Its annotation, Int -> a -> b, reads Array.indexedMap takes an index, any function, and returns a transformed function. Our two arguments come from (renderStep trackIndex) sequence. An index and array item are automatically pulled from the array, sequence, so our anything function is (renderStep trackIndex). As I mentioned earlier, parentheses contain functions, so while this looks like two arguments, it’s actually one.

Our error asking for Int -> a -> b but pointing out we’re passing Main.Clip -> Int -> Main.Step -> Html.Html Main.Msg says we’re passing the wrong thing to renderStep, the first argument. And we are. We haven’t passed in our clip yet. To pass values to functions when using an indexed map, they are placed before the automatic index. Let’s compare our type annotation to our arguments.

renderStep : Int -> Clip -> Int -> Step -> Html Msg

renderStep trackIndex trackClip stepIndex step = ...

Array.indexedMap (renderStep trackIndex) sequence

If sequence returns our step index and step, we can read our call as Array.indexedMap renderStep trackIndex stepIndex step which makes it very clear where our trackClip should be added.

Array.indexedMap (renderStep trackIndex trackClip) sequence

We need to modify renderSequence to accept the track clip, as well pass it through from renderTrack.

renderSequence : Int -> Clip -> Array Step -> List (Html Msg)

renderSequence trackIndex trackClip sequence =

Array.indexedMap (renderStep trackIndex trackClip) sequence

|> Array.toList

renderTrack : Int -> Track -> Html Msg

renderTrack trackIndex track =

div [ class "track" ]

[ p [] [ text track.name ]

, div [ class "track-sequence" ] (renderSequence trackIndex track.clip track.sequence)

]

Reducing Our Steps Into A Playback Sequence

Once we’re clear of errors our application renders again, and we can focus on reducing our playback sequence. We’ve already passed the track clip into the ToggleStep branch of the update function, but we haven’t done anything with it yet. The best time to add or remove clips from our playback sequence is when we toggle steps on or off so let’s update our model there.

Rather than use a let...in block in our branch, we create a private helper function to update our sequence. We know we need the position of the step in the sequence, the clip itself, and the entire playback sequence to modify.

updatePlaybackSequence : Int -> Clip -> Array (Set Clip) -> Array (Set Clip)

updatePlaybackSequence stepIndex trackClip playbackSequence =

let

updateSequence trackClip sequence =

if Set.member trackClip sequence then

Set.remove trackClip sequence

else

Set.insert trackClip sequence

in

Array.set stepIndex (updateSequence trackClip) playbackSequence

In updatePlaybackSequence we use Array.set to find the position of the playback sequence to update, and a local function, updateSequence to make the actual change. If the clip already exists, remove it, otherwise add it. Finally, we call updatePlaybackSequence from the ToggleStep branch in the update function to make the updates whenever we toggle a step.

ToggleStep trackIndex trackClip stepIndex step ->

( { model

| tracks = updateTrackStep trackIndex stepIndex model.tracks

, playbackSequence = updatePlaybackSequence stepIndex trackClip model.playbackSequence

}

, Cmd.none

)

Elm makes updating multiple record fields quite easy. Additional fields are added after a comma, much like a list, with their new values. Now when we toggled steps, we get a reduced playback sequence. We’re ready to pass our sequence data to JavaScript using a command.

Using Commands To Send Data To JavaScript

As I’ve mentioned, commands are side-effects in Elm. Think of commands as way to cause events outside of our application. This could be a save to a database or local storage, or retrieval from a server. Commands are messages for the outside world. Commands are issued from the update function, and we send ours from the UpdatePlaybackPosition branch. Every time the playback position is incremented, we send our clips to JavaScript.

UpdatePlaybackPosition _ ->

let

newPosition =

if model.playbackPosition >= 15 then

0

else

model.playbackPosition + 1

stepClips =

Array.get newPosition model.playbackSequence

|> Maybe.withDefault Set.empty

in

( { model | playbackPosition = newPosition }

, sendClips (Set.toList stepClips)

)

We use a local function to get the set of clips from the playback sequence. Array.get returns the set we asked for or nothing if it can’t find it, so we need to cover that case and return an empty set. We use a built-in helper function, Maybe.withDefault, to do that. We’ve seen several updates to our model thus far, but now we’re sending a command. We use sendClips, which we’ll define in a moment, to send the clips to JavaScript. We also need to convert our set to a List because that’s a type JavaScript understands.

sendClips is a small port function that only needs a type declaration. We send our list of clips. In order to enable the port, we need to change our update module to a port module. From module Update exposing (update) to port module Update exposing (update). Elm can now send data to JavaScript, but we need to load the actual audio files.

port module Update exposing (update)

port sendClips : List Clip -> Cmd msg

In JavaScript, we load our clips in a samples object, map over the list of clips Elm sends us, and play the samples within the set. To listen to elm ports, we call subscribe on the port sendClips, which lives on the Elm application ports key.

(() => {

const kick = new Howl({ src: ['https://raw.githubusercontent.com/bholtbholt/step-sequencer/master/samples/kck.mp3'] });

const snare = new Howl({ src: ['https://raw.githubusercontent.com/bholtbholt/step-sequencer/master/samples/snr.mp3'] });

const hat = new Howl({ src: ['https://raw.githubusercontent.com/bholtbholt/step-sequencer/master/samples/hat.mp3'] });

const samples = {

kick: kick,

snare: snare,

hat: hat,

};

const app = Elm.Main.embed(document.body);

app.ports.sendClips.subscribe(clips => {

clips.map(clip => samples[clip].play());

});

})();

Ports ensure type safety within Elm while ensuring we can communicate to any JavaScript code/package. And commands handle side-effects gracefully without disturbing the Elm run time, ensuring our application doesn’t crash.

Load up the completed step sequencer and have some fun! Toggle some steps, press play, and you’ve got a beat!

Wrapping Up And Next Steps

Elm has been the most invigorating language I’ve worked in lately. I feel challenged in learning functional programming, excited at the speed I get new projects up and running, and grateful for the emphasis on developer happiness. Using the Elm Architecture helps me focus on what matters to my users and by focusing on data modeling and types I’ve found my code has improved significantly. And that compiler! My new best friend! I’m so happy I found it!

I hope your interest in Elm has been piqued. There is still much more we could do to our step sequencer, like letting users change the BPM, resetting and clearing tracks, or creating sharable URLs to name a few. I’ll be adding more to the sequencer for fun over time, but would love to collaborate. Reach out to me on Twitter @BHOLTBHOLT or the larger community on Slack. Give Elm a try, and I think you’ll like it!

Other Resources

The Elm community has grown significantly in the last year, and is very supportive as well as resourceful. Here are some of my recommendations for next steps in Elm:

- Official Getting Started Guide

- A GitBook written by Evan, Elm’s creator, that walks you through motivations for Elm, syntax, types, the Elm Architecture, scaling, and more.

- Elm Core Library

- I constantly refer to the documentation for Elm packages. It’s written well (though the type annotations took a bit of time to understand) and is always up to date. In fact, while writing this, I learned about classList, which is a better way to write class logic in our views.

- Frontend Masters: Elm

- This is probably the most popular video course on Elm by Richard Feldman, who’s one of the most prolific members of the Elm community.

- Elm FAQ

- This is a compilation of common questions asked in various channels of the Elm community. If you find yourself stuck on something or struggling to understand some behavior, there’s a chance it’s been answered here.

- Slack Channel

- The Elm Slack community is very active and super friendly. The #beginners channel is a great place to ask questions and get advice.

- Elm Seeds

- Short video tutorials for learning additional concepts in Elm. New videos come out on Thursdays.

Further Reading

- SolidStart: A Different Breed Of Meta-Framework

- Web Development Is Getting Too Complex, And It May Be Our Fault

- Solving Media Object Float Issues With CSS Block Formatting Contexts

- How To Draw Radar Charts In Web