Web Standards: The What, The Why, And The How

The World Wide Web is an interesting place.

As the Internet has grown and become more common place, it has become a gigantic instrument of change in terms of the way in which we interact with the world and each other.

Like many people, my intro to web development at school was kind of bleak. Our school ICT (Information Computing Technology) lessons taught us very little, using Dreamweaver (back when it was a Macromedia product) as a platform to visually edit a personal website with the biggest lesson being “what is a hyperlink”. We didn’t even view the HTML source of our own websites!

So my education around HTML and CSS came largely from messing around with the “view source” option in websites. I learned through copy-pasting bits and pieces together to create my own websites and downloading templates for bootstrap, before I knew what bootstrap actually was.

Why Am I Telling You This?

Having recently surveyed my Twitter followers (it’s an exact science 😜), I discovered that a large chunk of people (43% of the people who voted), knew little to nothing about Web Standards and only 5% of those who voted were active contributors.

[poll] Are you a web developer or tinkerer? Have you built anything for the web before?

— Amy-ing for a PhD👩🏻💻✨ (@RedRoxProjects) 16. November 2018

Whether you're a total beginner or full-time web dev, please answer this question > What do you know about Web Standards?

RT for reach ✨👩💻

When you look at the ways in which people learn to do web development, it is totally understandable that this might be the case. The volume of online tutorials, boot-camps and online resources for learning how to build websites has lead to an increasing amount of self-taught web developers (like me) building stuff for the web.

This is one of the great successes of the Internet; anyone can learn almost anything — and there being more and more resources for learning outside of academia is really positive in terms of lowering barriers to access web development as a career.

Even with free resources online there are still a number of barriers in learning how to be a web developer. I’m not saying these don’t exist — they really do — and we should be doing more as a community to tackle these.

But with the diversification of learning processes comes several challenges, including information overwhelm and knowledge gaps.

When learning how to build web-flavored things, it is very easy to get wrapped up in “how do I build the thing?” This can result in not equally considering the “why should I build it this way?” or “what are all the options for building the thing?”

Consequently, it is equally as easy to become overwhelmed with the many number of ways to solve your web related problem. This can result in picking the first solution from the results of an internet search, without considering whether it is the better (in terms of most robust, accessible and secure) of the options available.

Web Standards and the documentation to support Web Standards, provide a lot of insight about ‘the why’ and ‘the what’ of the world wide web. They are a fantastic resource for any web developer and help you to build things for the web that are functional, accessible and cross-compatible.

This post is designed to help anyone with an interest in the web who wants to get to know more about web standards. We will cover:

- An introduction to web standards (what are they, why do they exist and who makes them);

- How to navigate and make use of standards in your work;

- Ways you can get involved in contributing to new and existing standards.

Let’s begin our introduction to web standards by asking, “Why do we need standards for the web?”

The World Wide Web Before Standards

We can think of the world wide web as an information ecosystem. People create content that is fed into the web. This content is then passed through a browser to allow people to access that information.

Before Web Standards, there weren’t many fixed rules for any part of this system; no formal rules as to how the content should be created, nor any requirements in terms of how a browser should serve up that information to the people that are requesting it.

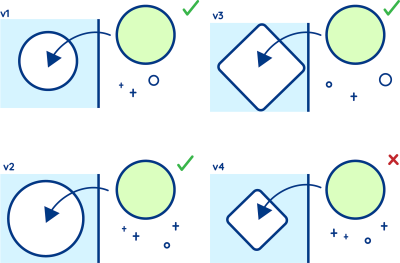

So, in a way, the web operated a bit like that children’s toy where you have to sort the different shaped blocks into the correct holes. In this analogy, the different types of browsers are the different shaped holes and the content or websites, are the brightly colored blocks.

In the past, as a content creator you would make a website to fit the browser it would be intended for. For example, you would create an IE-shaped block to be able to pass this through the Internet Explorer hole.

This meant that this website block you had created would only fit through that one hole and you would need to rebuild your content into other shapes for it to be viewed using any of the other browsers.

Developers in the 90s would often have to make three or four versions of every website they built, so that it would be compatible with each of the browsers available at the time. And what is more, browser makers in attempts to better their competition would introduce “features” that diversified their approach from their competitors.

In the beginning, it was probably fairer to say our Internet browser to content-matching toy looked more like this:

This was because browsers were built to handle pretty much the same stuff, which was largely text-based content. So, for the most part, a website block would fit through the majority of the holes, with the exception of maybe one where it might fit — but not perfectly.

As the browsers developed, they begin to add features (e.g. by changing their shape) and it became more and more difficult to make a block that would pass through each of the browser holes. This even meant that a block that could once fit through one particular hole, didn’t fit through that hole any longer; adding these features into the browser would often result in poor reverse compatibility.

This was really damaging for some developers. It created a system in which compatibility was limited to the content creators that could afford to continuously update and refactor their websites for each of the available browsers. For everyone else, every time a new feature or version was released, there was a chance your website would no longer work with that browser.

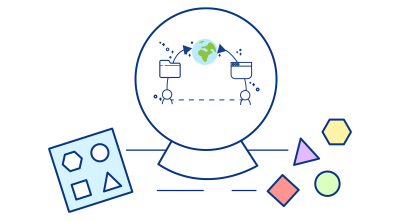

Web standards were introduced to protect the web ecosystem, to keep it open, free and accessible to all. Putting the web in a protective bubble and disbanding with the idea of having to build websites to suit specific browsers.

When standards were introduced, browser makers were encouraged to adhere to a standardized way of doing things — resulting in cross-compatibility becoming easier for content makers and there no longer being the need to build multiple versions of the same website.

Note: There are still a number of nuances about cross-compatibility amongst browsers. Even today, over 20 years since standards were introduced, we aren’t quite at “one-size fits all” just yet.

Here’s a quick look at some of the key moments in the history of web browser development:

| Year | Key moments |

|---|---|

| 1990 | Sir Tim Berners Lee releases the WorldWideWeb, the first way in which to browse the web. |

| 1992 | MidasWWW was developed as another WWW browser, which included a source code viewer. |

| 1992 | Also in 1992 Lynx was released, which was a text-based web browser, it could not display images or any other graphic content. |

| 1993 | NCSA Mosaic was released, this is the browser that is credit for being the first to popularize web browsing as it allowed the display of image embedded within text. |

| 1995 | Microsoft released Internet Explorer, previously Cello or Mosaic browsers were used on Windows products. |

| 1996 | Opera was released publicly, it was previously a research project for a Norwegian telecoms company Telnor. |

| 2003 | Safari was released by Apple, previously Macintosh computers shipped with Netscape Navigator or Cyberdog. |

| 2004 | In the wake of Netscape Navigator’s demise, Firefox was launched as a free, open-source browser. |

| 2008 | Chrome was launched by Google and within six years grew to encompass the majority of the browser market. |

| 2015 | Microsoft released Edge, the new browser for Microsoft, replacing Internet Explorer from Windows 10 onwards. |

Source: “Web Browsers: A Brief History” by Rhiannon Williams

Why We Need Standards

Knowing a bit about the history of standards and why they were introduced, we can start to see the benefits of having standards for the World Wide Web. But why is it important that we continue to contribute to Web Standards? Here are just a few reasons:

Keeping The Web Free And Accessible To All

Without the Web Standards community, browser makers would be the ones making decisions on what should and shouldn’t be features of the world wide web. This could lead to the web becoming a monopolized commodity, where only the largest players would have a say in what the future holds.

Helping Make Source Code Simpler; Reducing Development And Maintenance Time

As more browsers appeared and browser makers began to diversify in their approach, it became more and more difficult to create content that would be served in the same way across multiple browsers. This increased the amount of work required to make a fully compatible website, including bloating the source code for a web page. As developers today we still have to do the odd include [X script] so this works on [X web browser], but without Web Standards, this would be much worse.

Making The Web A More Accessible Place

Web standards help to standardize the way in which a website can interact with assistive technologies. Meaning that browser makers and web developers can incorporate instructions into their pages which can be interpreted by assistive technologies to maintain a common (or sometimes better) end-user experience.

Allowing For Backward Compatibility And Validation

Web standards have created a foundation which allows for new websites, that comply with standards, to work with older browser versions. This idea of backward compatibility is super important for keeping the web accessible. It doesn’t guarantee older browsers will show your content exactly as you expect, but it will ensure that the structure of the web document is understood and displayed accordingly.

Helping Maintain Better SEO (Search Engine Optimization)

Another of the major hidden benefits (at the time that Web Standards was first introduced) was that a Web Standards compliant website was more discover-able by search engines. This became more evident when the Google search became the major player in the search engine world in the early 2000s.

Creating A Pool Of Common Knowledge

A world with web standards creates a place in which a set of rules exists, rules that every developer can follow, understand and become familiar with. In theory, this means that one developer could build a website that complies with standards and another developer could pick up where the former left off without much trouble. In reality, standards provide the foundation for this; but the idea relies heavily on developers writing well-documented code.

Who Decides On What Becomes A Web Standard?

Standards are created by people. In the web and Internet space, there is a strong culture of consensus — which means a lot of talking and a lot of discussions.

The groups through which standards are developed are sometimes referred to as “Standards Development Organisations” or SDOs. Key SDOs in the web space include the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the WHATWG, and ECMA TC39. Historically there were also groups like the Web Standards Project (WaSP), that advocated for Web Standards to be adopted by organizations.

The groups that work on the Internet and Web Standards generally operate under a royalty-free regime. That means when you make use of a web standard you don’t have to pay anyone — like someone who might hold a relevant patent. Whilst the idea that you might have to pay royalties to someone to build a web browser or website might seem absurd right now, it wasn’t too long ago that organizations like BT were trying to assert ownership of the concept of the hyperlink. Standards organizations like the ones listed below help keep the web free (or free from licensing fees at least).

What Is IETF?

The IETF is the grandparent of Internet standards organizations. It’s where underlying Internet technologies like TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) and DNS (Domain Name System) are standardized. Another key technology developed in IETF is something called Hyper-Text Transport Protocol (HTTP) which you may have heard of.

If you’ve been paying attention to the rise of HTTP2 and the subsequent development of (UDP-based) HTTP3, this is where that work happens. Most of the work in IETF is focused on the lower levels of the Open Systems Interconnection model.

What Is W3C?

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is an international community where member organizations, a full-time staff, invited experts and the public work together to develop Web Standards. Led by Web inventor and Director Tim Berners-Lee and CEO Jeffrey Jaffe, W3C’s mission is to lead the Web to its full potential.

The community was founded in 1994 at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) in collaboration with CERN. At the time of this post, W3C has 475 member companies and organizations and exists as a consortium between 4 academic institutions: MIT (USA), ERCIM (France), KEIO University (Japan) and Beihang University (China).

Work in W3C happens in working groups and community groups. Community groups are where a lot of initial innovation happens around new web technologies. New web standards can be produced by community groups but they are officially seen as “pre-standard.” Community groups are open for anyone to participate, whether or not the organization you work for or are affiliated with is a W3C member.

W3C working groups are where new web standards are officially minted. Working groups usually start with a submission of a standard, often something that is already shipping in some browsers. However, technical work on refining these standards happens within these groups before the standard goes for final approval as a “W3C Recommendation.” By the time something reaches “recommendation” phase in W3C, it’s most often implemented and in wide use across the web.

Working groups are more difficult for people who are not affiliated with a member organization to become a part of. However, you may become an invited expert to a group. One reason why working groups are a little more difficult to join and operate with more process is that they also act as an intellectual property holder — through joining a W3C working group organizations and companies agree to the royalty-free licensing laid out in W3C’s patent policy.

W3C Advisory Board member Natasha Rooney has put together a great document, W3C Process Document for Busy People, that explains a lot of the ins and outs of working in W3C.

What Is The WHATWG?

The WHATWG was originally a splinter group from the W3C. It was formed in 2007 because some browser vendors didn’t agree with the direction in which the W3C was pushing HTML. WHATWG continues to be the place where HTML is developed and evolved. However, the community of participation in the HTML specification still includes many people from the W3C community, and many WHATWG-affiliated people participate in W3C working groups.

At the time of this post, the relationship between the W3C and the WHATWG remains in flux. From a developer perspective, this doesn’t matter too much because developers can rely on resources like MDN to reflect the “truth” of which web technologies can be used in specific browsers. However, it has led to a lack of clarity, in terms of where to participate in the development of certain standards. WHATWG also has its own royalty-free license agreement — the WHATWG participation agreement.

What Is The “Why CG”?

The Web Incubator Community Group (WICG, pronounced Why-CG) is a special community group, within W3C, where some new and emerging web technologies are discussed and developed.

If you have a great idea for a new standard, a new feature for an existing standard or a new technology you think ought to be incorporated into the web, it’s worth checking here first to see if something like it is already being discussed. If it is, great! Jump into these discussions and lend your support. If not, then suggest it! That’s what this group is for.

What Is The ECMA TC39?

Ecma is a standards organization for information and communication systems, which was founded in 1961 to standardize computer systems in Europe. Its name comes from being previously known as the “European Computer Manufacturers Association” but it is now referred to as “Ecma International — European association for standardizing information and communication systems” since the organization went global in 1994.

The ECMA-262 standard outlines the ECMAScript Language Specification, which is the standardized specification of the scripting language known as JavaScript. There are ten editions of ECMA-262 that have been published (the tenth edition was published in June 2018).

TC39 (Technical Committee 39) is the committee that evolves JavaScript. Like the other groups listed here, its members are companies which include most of the major browser makers. The committee has regular meetings which are attended by delegates sent from the member organizations and also by invited experts. The TC39 operates on achieving consensus, as with many of the other groups, and the agreements made often lead to obligations for its members (in terms of future features that member organizations will need to implement). The TC39 process includes accelerating proposals through a set of stages, the progression of a proposal from one stage to the next must be approved by the committee.

What Was The Web Standards Project?

The Web Standards Project was formed in 1998 as a resistance to the feature face-off happening between browsers in the 90s; with a primary goal of getting browser makers to comply with the standards set forth by the W3C.

As the organization grew and the browser wars ended, the project began to shift focus. The group began working with browser makers on improving their standards support, consulting software makers that created tooling for website creation and educating web designers and developers on the importance of web standards. The last of these points, resulted in the creation of the InterAct web curriculum framework which is now maintained by W3C.

The Web Standards Project ceased to be active in 2013. A final blog post was created on March 1st that gives thanks to the hard work of the members and supporters of the project. In the closing remarks of this post, readers are reminded that the job of the Web Standards Project is not entirely over, and that the responsibility now lies with thousands of developers who continue to care about ensuring the web remains a free, open, inter-operable and accessible resource.

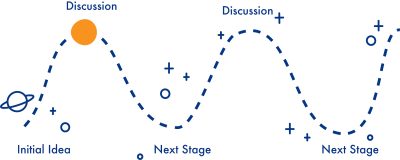

How Does Something Become A Web Standard?

So, how are standards made? The short answer is through LOTS of discussions.

Proposals for new standards usually start as a discussion within a community group (this is especially the case in W3C) or through issues raised on the relevant GitHub repository.

Across the different SDOs, there seems to then be a common theme of ascension; after the discussion has begun, it then moves up within the organization, and at each level, a deciding committee needs to reach a consensus to approve the elevation of that discussion. This is repeated until the discussion becomes a proposal, then that proposal becomes a draft and the draft goes on to become an official standard.

Now as previously mentioned, when something isn’t an official standard, this does not necessarily mean that it is not in use within some browsers. In fact, by the time something becomes a standard, it is likely to already have widespread use across many of the available browsers. In this instance, the role of the standard is part of the normalizing and adoption process for new features; it sets out the expected use for something and then outlines how browser makers and developers can conform to this expectation.

What Is TPAC?

Every year, W3C holds one massive event, a week-long multi-group meeting punctuated by a one-day unconference on the Wednesday (the Technical Plenary) combined with a meeting of its Advisory Committee (a group consisting of one person for every organization or company that is a W3C member). Put Technical Plenary and Advisory Committee together, and you get TPAC (often pronounced tee-pac). Although it’s a W3C-run event, you will often find people “from” WHATWG, IETF or TC39 here as well.

This past year, Samsung Internet people came together to participate in TPAC. We also sponsored diversity scholarships which are intended to bring people from under-represented groups to TPAC and to the Web Standards community.

My First TPAC

When I first heard the team talking about TPAC, I had no idea what to expect. After reading up about the event on the TPAC website, I signed myself up and booked my travel. Soon enough, I was on a train from London to Lyon with the team.

On arrival, I was given my Lanyard and a map of the various rooms where all the action was happening. My goal, for the three days I was attending, was to join in with as much accessibility type things as I could. Having arrived shortly after things had begun on my first day, I stood staring at a closed door for the Accessibility Guidelines working group that I wanted to sit in on. Lots of things went through my mind at that moment; “Perhaps I should wait until the break?” “No, don’t be silly, that’s still an hour away.” “Maybe I should knock?” “But wouldn’t that be more interruptive than just going in?” “Maybe I shouldn’t go in at all…” But after a few minutes, I worked up the courage to walk into the room.

There was a round table set up (which is typical of a lot of these sessions) with folks sitting at the tables with laptops; along with a number of seats arranged around the edge of the room for people to join in a more observational role. Each group also had a chat room on IRC, which anyone from the W3C membership could join (whether attending TPAC in person or not). I sat at the end of one of the tables; though I’m still not sure whether that was the proper thing to do in terms of etiquette.

Initially, I was worried that my presence stuck out as much as the gigantic bear statue outside the venue; but no-one in the room paid any mind to my arrival and so the discussion continued. The group was about to move onto receiving an update on the work being done by the Silver Task Force; a community group that is trying to make the accessibility standards themselves more accessible.

It was really interesting to sit at the table for these discussions. Whilst as a first-time attendee, some of the language took some getting used to (terms like ‘conformance’ and ‘normative’); it was super nice to be inside of a room full of people who cared so much about accessibility. Many of the attendees of this working group spoke from a position of lived experience in terms of using the web with an accessibility requirement. Having spent my last three years researching accessibility requirements in digital music technology, I felt quite at home following along with the questions raised by the members of this group.

The work showcased by the Silver Task Force in this first discussion really sparked an interest for me. It felt like quite a refreshing viewpoint of how to make standards, in general, more accessible and frame them in such a way that makes for easier navigation and more tailored advice and guidance. For the following few days, I joined this (much smaller) group and had the chance to input into the conversations — which was really positive. Since TPAC, I have joined the community group for the Silver Task Force and have plans to join the weekly meetings in the new year.

One of the nice things about TPAC (for those not chairing a working group or in some sort of leading role) was the ability to dip in and out of sessions. In amongst the things I attended over the few days I was at TPAC, there was a session from the Web Incubator community group (WICG), a developer meet-up with talks from prominent community members and demonstrations of new web technologies, and a Diversity and Inclusion for W3C meeting. An extra added bonus of going to TPAC with the Samsung Internet team was that we got to meet up with people from our team based in Korea, as well as other Samsung team members from the USA.

How To Use Web Standards In Your Work

So, now that you know the why and wherefore of Web Standards, how do you go about using web standards in your work?

Mozilla Developer Network Web Docs (MDN Web Docs)

We (the Samsung Internet team) recommend that if you’re interested in learning more about a particular web standard or technology, you start with the MDN (Mozilla Developer Network) Web Docs. Whilst MDN WebDocs started as Mozilla Project, more recently it has become the place web developers go for cross-browser documentation on web platform technologies.

Last year, Samsung joined Bocoup, Google and Microsoft and W3C to form the MDN WebDocs Product Advisory Board to help ensure that MDN maintains this position.

When you search a technology in MDN, you will see a browser compatibility matrix letting you know what the browser support is. You will also find a link to the most relevant and up to date version of the standard. When you follow a link to a standard, you will be directed to the relevant web page outlining that standard and its technical specifications. These pages can be a little overwhelming at first, as they are somewhat ‘academic’ in structure.

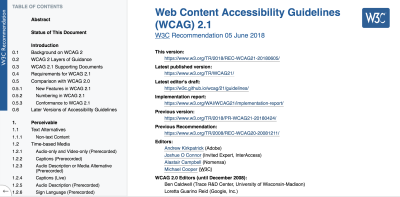

To give you some tips on navigating the documentation, let’s take a look at a standard I’m most familiar with: the W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (2.1).

This is the format of a W3C web standard. It features a table of contents on the left-hand side of the page while the content is organized into very structured headers — starting with the version, reports and editors details. These headers in standards are often used to quote the relevant parts of a standard “Oh, but WCAG 2.1 1.2.2 says”; but for those without the alphanumeric memory of a hard-disk, do not fear, it is not a requirement that you have to know these things by heart.

My first piece of advice about navigating web standards is to try not to be overwhelmed by these. If you’ve come from the non-academic route into web development like me, the structure of these documents can at first seem quite formal, and the language can feel this way, too. Don’t let this be a reason to navigate away from using this as a source of information — as quite frankly it is the best source of information available for finding out how and why web things work in the way that they do.

Here are some quick tips for working with web standards:

- The TL;DR version

Firstly, it’s important to understand that there isn’t a TL;DR for web standards. The reason they are these long and comprehensive documents is because they have to be. There can’t be any stone unturned when it comes to exacting the structure and expected us of web development things. However (a pro tip, and a way to avoid information overwhelm), is to start with the abstract of the standard and follow any links to introductory documents. In my example, the WCAG 2.1 standard document leads us to another linked page for the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Overview. Which provides a range of useful documentation including a quick reference guide on how to meet WCAG 2.

- Make use the glossary of terms

This just helps to understand the exact meaning of words and phrases in the context of the web standard . Let’s face it; there are so many terms out there with multiple meanings. Checking out the glossary also helps navigate some of the more academic terms.

- ‘Find in page’ is your friend

Once you have familiarized yourself with an overview and got an idea about the terms used within a web standard, you can start to search through the documentation for the information you require. The web standards are designed in such a way that you can consume them in a number of ways. If you seek to gain a comprehensive understanding then reading from start to finish is advised; however, you can also drop in and out of the sections as you require them. The good folks creating web standards have made efforts to ensure that referential content is linked to the source and any helpful resources are also included, which helps support the kind of “on demand” usage that is common. Take this example from WCAG 2.1:

- If you’re not sure — ask!

This community is put together from a bunch of people who care and have an investment in the future of web technologies. If you want to make sure you are adhering to Web Standards but maybe have got caught up in a language barrier, and you’re struggling to interpret what is meant by a phrase within a web standard, there are many folks out there that can help. You can raise issues through the W3C GitHub repositories for the W3C Web Standards or join the conversations about Web Standards through the suggested resources on the participate section of the W3C website.

How Do I Get Involved?

So, now that you know how to read up on your standards, what about getting involved?

Well, here are a few places to start:

- GitHub repositories for standards

The WC3, TC39, WhatWG and WICG all have organizations on GitHub that contain repositories for the work they are doing. Be sure to check in on the READme, contribution guidelines and code of conduct (if there is one) before you begin. Use the issues of a repository to look at what is currently being discussed in terms of future developments for the standard it relates to. - The W3C website

Here you can look at all the working groups, community groups, and forums. It is a great place to start; if you join the organization and become a member of a community group or working group you’ll be invited to the ongoing discussions, meetings, and events for that group. - The WhatWG website

For all things WhatWG. Here there are guides on how to participate, FAQs, links to the GitHub repositories and a blog that is maintained by members of the WhatWG. - The WICG website

Whilst the Web Incubator Community Group can be found from the W3C website, they are worth a separate shout-out here as they have their own web community page and Discourse instance. (For those of you not familiar with Discourse, it allows communities to create and maintain forums for discussion.) - The TC39 standard

This is pretty comprehensive and includes links to the ways in which you can to contribute to the standard. - Speak to Developer Advocates

Many Web Developer Advocates are members of an SDO or known to be working on standards; teams like ours (the Samsung Internet Developer Advocates) are often involved in the work of Web Standards and happy to talk to developers that are interested in them. After all, standards have a huge impact on the future of the web and in turn the work that we do. So, depending on the web standard that interests you, you’ll be able to find folks like us (who are part of the work for those standards) through social media spaces like Twitter or Mastodon.

Thanks for reading! Remember that web standards impact everyone that builds or consumes websites, so the work of Web Standards is something we should all care about.

If you want to chat more about web standards, accessibility on the web, web audio or open-source adventures — you can find me on Twitter. ✨

A huge thanks to Daniel Appelquist, who helped bring this article together.

Further Reading

- Mobile Accessibility Barriers For Assistive Technology Users

- A Web Designer’s Accessibility Advocacy Toolkit

- Useful DevTools Tips and Tricks

- How To Become A Better Speaker At Conferences

Register Free Now

Register Free Now Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App