Using WebXR With Babylon.js

Immersive experiences, especially those governed by mixed reality (XR), which encompasses both augmented and virtual reality, are quickly gaining new attention among developers and architects interested in reaching users and customers in novel ways. For many years, the lack of adoption of mixed reality experiences came down to hardware — too expensive and unwieldy — and software — too complex and finicky to use.

But the Coronavirus pandemic may be scrambling all of those old calculations by encouraging the sorts of experiences that are mostly limited to the gaming world, which is seeing immense growth in playing time during the current crisis. The math behind three-dimensional spaces can also present barriers to developers, but fortunately, you need only a little vector geometry and matrix math to succeed with XR experiences, not a college course in linear algebra and multivariate calculus.

Though browser support for WebXR is widening, building immersive experiences into browsers or headsets can be complicated due to shifting specifications and APIs as well as rapidly evolving frameworks and best practices. But incorporating immersion into your next web application can also introduce new dimensionality and richness to your user experience — all without the need to learn a new programming language.

- What Is WebXR?

- The WebXR Specification And Browser Support

- Field Of View (FOV) And Degrees of Freedom (DoF)

- WebXR Session Modes

- Setting A Scene With WebXR And Babylon.js

- Introducing Babylon.js

- Lights, Camera, Action!

- Taking Shape: Set And Parametric Shapes

- Putting It All Together: Rendering The Scene

- Next Steps: Supporting And Managing User Input

- Debugging, Extending, And Bundling Babylon.js

- Immersing Yourself In WebXR

What Is WebXR?

Simply put, WebXR is the grouping of standards responsible for supporting rendered three-dimensional scenes in virtual and augmented reality, both experiential realms known together as mixed reality (XR). Virtual reality (VR), which presents a fully immersive world whose physical elements are entirely drawn by a device, differs considerably from augmented reality (AR), which instead superimposes graphical elements onto real-world surroundings.

WebXR-compatible devices run the gamut from immersive 3D headsets with built-in motion and orientation tracking and names like Vive, Oculus, and Hololens to eyeglasses with graphics placed over real-world images and smartphones that display the world — and additional elements — on their native cameras.

The WebXR Specification And Browser Support

The WebXR Device API is the primary conduit by which developers can interact with immersive headsets, AR eyeglasses, and AR-enabled smartphones. It includes capabilities for developers to discover compatible output devices, render a three-dimensional scene to the device at the correct frame rate, mirror the output to a two-dimensional display (such as a 2D web browser), and create vectors that capture the movements of input controls.

Currently a working draft, the WebXR specification is a combination of the foregoing WebVR API, which was designed solely for virtual reality use cases, and the all-new WebXR Augmented Reality Module, which remains highly experimental. WebVR, formerly the predominant and recommended approach for virtual reality experiences, is now superseded by WebXR, and many frameworks and libraries offer migration strategies between WebVR and the newer WebXR specification.

Though WebXR is now witnessing adoption across the industry, browser support remains spotty, and it’s not yet guaranteed that a mixed reality application built according to the WebXR specification will work off the shelf in production.

Chrome 79, Edge 79, Chrome for Android 79, and Samsung Internet 11.2 all offer full WebXR support. But for unsupported browsers like Firefox, Internet Explorer, Opera, Safari, or certain mobile browsers (Android webview, Firefox for Android, Opera for Android, and Safari on iOS), there’s a WebXR Polyfill available thanks to WebXR community members that implements the WebXR Device API in JavaScript so that developers can write applications according to the latest state of the specification. On Firefox for web and Firefox for Android, you can enable the experimental feature flag by navigating to about:config and setting dom.vr.webxr.enabled to true in your browser’s advanced settings.

Installing the WebXR API Emulator on Chrome or Firefox on a personal computer will introduce additional tools to help you with debugging and testing.

The WebXR Device API depends on WebGL (Web Graphics Library), the rendering engine that supports three-dimensional graphics, and therefore employs many WebGL concepts when it performs the rendering, lighting, and texturing needed for a scene. Though the deepest reaches of WebGL are well beyond the scope of this article, those already familiar with WebGL will benefit from existing expertise.

Several open-source JavaScript frameworks are available to interact with WebGL and WebXR, namely Three.js and Babylon.js. A-Frame, a browser-based, markup-focused approach to WebXR, is built on top of Three.js. In this tutorial, we spotlight Babylon.js, which has gained attention as of late due to its large API surface area and relative stability. But these aren’t like the JavaScript libraries and frameworks we use to build two-dimensional web applications; instead, they play in the sandbox of three-dimensional spaces.

Field Of View (FOV) And Degrees Of Freedom (DoF)

In this article, we’ll focus on building a simple immersive experience with limited input and a static object, which means our need for deep knowledge about WebGL is minimal. But there are critical WebXR concepts outside of WebGL that are fundamental not to three-dimensional graphics themselves but how to interact with three-dimensional spaces. Because WebXR is rooted in a viewer’s experience, everything revolves around the immersive headset or viewport the user faces.

All headsets and smartphones have a camera serving as the user’s viewport into an immersive experience. Every camera has a certain field of view (FOV) that encompasses the extent of the viewer’s surroundings that is visible at any given time in a device. A single human eye has an FOV of 135º, while two human eyes, with overlapping FOVs, have a combined FOV of 220º wide. According to MDN, most headsets range between 90º to 150º in their field of view.

The virtual or augmented world seen through the camera’s field of view can be adjusted through movement, which occurs along degrees of freedom whenever a device is shifted in certain ways while the user remains stationary. Rotational movement occurs along three degrees of freedom (3DoF), which is a baseline for most basic immersive headsets:

- Pitch is movement incurred by looking up and down. In pitch, the user’s head pivots on the x-axis, which extends horizontally across the viewport.

- Yaw is movement incurred by looking left and right. In yaw, the user’s head pivots on the y-axis, which extends vertically across the viewport.

- Roll is movement incurred by tilting left and right. In roll, the user’s head pivots on the z-axis, which extends forward into the viewport and into the horizon.

Though three degrees of freedom are sufficient for simpler immersive experiences, users typically wish to move through space rather than merely changing their perspective on it. For this, we need six degrees of freedom (6DoF), whose latter three degrees define translational movement through space — forward and reverse, left and right, up and down — to pitch, yaw, and roll. In short, 6DoF includes not just pivoting along the x-, y-, and z-axes but also moving along them. Due to the frequent requirement of external sensors to detect translational movement, only high-end headsets support all six degrees.

WebXR Session Modes

With WebXR superseding the foregoing WebVR specification, it now provides one API as a single source of truth for both augmented and virtual reality. Each WebXR application begins by kicking off a session, which represents an immersive experience in progress. For virtual reality, WebXR makes available two session modes: inline, which deposits a rendered scene into a browser document, and immersive-vr, which depends on a headset. For augmented reality, because rendering is only possible into smartphone cameras and transparent glasses or goggles instead of browsers, immersive-ar is the only available mode.

Because many of us don’t have an immersive headset handy at home, and because the WebXR Augmented Reality Module remains in heavy development, we’ll focus our attention on an immersive VR experience that can be rendered into a browser canvas.

Setting A Scene With WebXR And Babylon.js

In this section, we’ll learn how to create and render a WebXR scene with Babylon.js, the surroundings of our environment and the setting of our experience, before turning any attention to actions like user input or motion. Babylon.js is a free and open-source web rendering engine based on WebGL that includes support for WebXR and cross-platform applications in the form of Babylon Native. Babylon.js offers a slew of additional features, including a low-code Node Material Editor for shader creation, and deep integration with WebXR features like session and input management. The Babylon.js website also provides playground and sandbox environments.

Though selecting between Babylon.js and Three.js comes down to developer preference, Three.js focuses on extensibility over comprehensiveness, with a host of interchangeable modules that add supplemental functionality. Babylon.js, meanwhile, provides a more full-featured suite that may prove overkill for smaller projects but does offer the needed surface area for many implementations.

Introducing Babylon.js

Though you can handle all of the interactions with the WebXR Device API yourself, Babylon.js provides an optional Default Experience Helper that can set up and shut down sessions on your behalf. The Default WebXR experience helper also includes input controls and other features, as well as a rudimentary HTML button to enter the immersive experience. To experiment with the default experience helper, let’s write an HTML page that provides a canvas for XR display and serves the Babylon.js source from a CDN. You can find this HTML page at the GitHub repository for this tutorial on the main branch.

Open index.html in your preferred code editor and in a browser. For this first portion of the tutorial, we’ll inspect the file instead of adding code. In a WebXR-enabled browser like Chrome or Firefox (with the WebXR feature flag enabled in the case of Firefox), you’ll see a canvas containing the initial Babylon.js playground — a “Hello World” of sorts — and you can drag your mouse on the screen to reorient yourself. The screenshot below depicts this initial state.

First, we’ll embed the latest versions of Babylon.js from the Babylon CDN as well as other helpful dependencies. We’ll also add some styles for our scene canvas element in <body>, which is where our immersive experience will render.

<!-- babylon-webxr/index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Babylon WebXR Demo</title>

<!-- Embed latest version of Babylon.js. -->

<script src="https://cdn.babylonjs.com/babylon.js"></script>

<!-- Embed Babylon loader scripts for .gltf and other filetypes. -->

<script src="https://cdn.babylonjs.com/loaders/babylonjs.loaders.min.js"></script>

<!-- Embed pep.js for consistent cross-browser pointer events. -->

<script src="https://code.jquery.com/pep/0.4.3/pep.js"></script>

<style>

html, body {

overflow: hidden;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

#render-canvas {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

touch-action: none;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<canvas id="render-canvas"></canvas>

Now it’s time for our Babylon.js implementation. Inside a <script> element just before the terminal </body> tag, we start by identifying our canvas element to Babylon.js during the instantiation of a new Babylon engine with default configuration.

<!-- Our Babylon.js implementation. -->

<script>

// Identify canvas element to script.

const canvas = document.getElementById('render-canvas');

// Initialize Babylon.js variables.

let engine,

scene,

sceneToRender;

const createDefaultEngine = function () {

return new BABYLON.Engine(canvas, true, {

preserveDrawingBuffer: true,

stencil: true

});

};

Lights, Camera, Action!

For our viewers to be able to immerse themselves in our experience, we need to define a camera to be positioned at a viewpoint and oriented in a direction along which a viewer can perceive an environment. We also need to provide a source of lighting so that viewers can see the scene. Though the WebXR Device API offers low-level WebGL-based mechanisms to create cameras, Babylon.js comes with a full camera implementation.

A Quick Aside On WebXR Geometry

Before we proceed, however, it’s important for us to take a quick detour to examine some essential concepts in three-dimensional geometry in WebXR and WebGL, from which WebXR inherits geometric concepts. In order to understand position, rotation, and scaling in WebXR and Babylon.js, we need to understand three-dimensional vectors, matrices, world and local spaces, and reference spaces. And to position, rotate, and scale objects in three-dimensional space, we need to use matrix transformations.

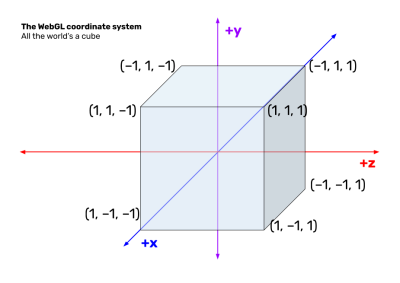

In a typical two-dimensional coordinate plane, we express origin as the coordinates (0, 0), where the x- and y-values are both equal to zero. In three-dimensional space, on the other hand, we need a three-dimensional vector, which adds a third axis, the z-axis, which is perpendicular to the plane represented by the x- and y-axes. (If the x- and y-axes of a coordinate plane are a piece of paper, the z-axis jumps up from the page.) Given that WebGL, and thus WebXR, expresses a single unit as one meter, the three-dimensional vector (0, 1, 2) would have an x-value of 0, a y-value of 1 meter, and a z-value of 2 meters.

WebGL and WebXR distinguish between world spaces and local spaces according to the frame of reference or reference space you are operating in. The standard WebGL coordinate space or world space is represented by an imaginary cube that is 2 meters wide, 2 meters high, and 2 meters deep, and every vertex of the cube is represented by a vector whose values are one meter away from the origin (0, 0, 0), as the diagram below illustrates. When you put on a headset and kick off a virtual reality experience, you are located at the origin — that is, (0, 0, 0) — of world space, with the –y-axis before you, the –x-axis to your left, and the –z-axis below your feet. Typically, a WebXR device’s initial location is the origin of world space.

Each object, including both entities in space and input controllers like joysticks, has its own frame of reference or reference space that relates back to the global frame of reference represented by world space, whose origin is usually updated in real time based on the viewer’s position. This is because every object and input source has no awareness of other objects’ and input sources’ positions. The object- or controller-specific frame of reference is local space, represented as a matrix, and every position vector or transformation on that entity is expressed according to that local space. This means that a typical WebXR scene might consist of dozens or scores of distinct reference spaces.

As an example of this, consider a sphere with no transformations that is located at (1, 3, 5), which is its native origin in world space. According to its local space, however, it is located at (0, 0, 0), which is its effective origin. We can reposition, rotate, and scale the sphere in ways that modify its relationship to its local space, but during rendering, we’ll eventually need to convert those shifts into transformations that make sense back in world space, too. This requires conversion of the sphere’s local space matrix into a world space matrix according to the origin offset (the difference between the native and effective origins). The arithmetic behind these operations involves matrix transformations, whose full exploration is well beyond the scope of this article, but MDN has an excellent introduction. Now, we can start to position our first camera.

Cameras

First, we instantiate a new scene and a new camera, positioned at the three-dimensional vector (0, 5, –10) (i.e. x-value of 0, y-value of 5, z-value of –10), which will position the camera 5 units above and 10 units behind the WebXR space’s native origin of (0, 0, 0). Then, we point the camera to that very origin, which angles it slightly downwards (y-value of 5) and leaves any scene objects in front of us (z-value of –10).

// Create scene and create XR experience.

const createScene = async function () {

// Create a basic Babylon Scene object.

let scene = new BABYLON.Scene(engine);

// Create and position a free camera.

let camera = new BABYLON.FreeCamera('camera-1', new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 5, -10), scene);

// Point the camera at scene origin.

camera.setTarget(BABYLON.Vector3.Zero());

// Attach camera to canvas.

camera.attachControl(canvas, true);

If we subsequently perform local transformations to the camera’s position, those will operate on the camera’s effective origin. For richer camera capabilities or access to lower-level features, you can use the WebXRCamera prototype instead.

Lights

If we were to display this scene to our viewers, they would see nothing, because there isn’t a source of light in the environment to transmit particles that will bounce off objects into our eyes. In mixed reality, there are three possible components of a light source, each representing a type of lighting, as described by MDN:

- Ambient light is omnipresent and doesn’t come from a single point or source. Because the light is reflected equally in all directions, the effect of ambient light is equivalent no matter where you are in a scene.

- Diffuse light is light that is emitted from or reflected off of a surface, evenly and in a direction. The angle of incidence (the angle between the vector representing the direction of light reaching an object’s surface and the vector perpendicular to the object’s surface) determines the intensity of the light across the object.

- Specular light is the type of light that marks shiny or highlighted areas on reflective objects like jewelry, eyes, dishes, and similar objects. Specular light presents itself as bright spots or boxes on an object’s surface where the light is hitting the object most directly.

Babylon.js provides a HemisphericLight prototype for ambient light that we can use to instantiate a new light source. In this case, we’re positioning the hemispheric light to point upwards towards the sky with the vector (0, 1, 0).

// Create a light and aim it vertically to the sky (0, 1, 0).

let light = new BABYLON.HemisphericLight('light-1', new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 1, 0), scene);

Light Sources

Babylon.js provides four types of light sources that can employ ambient, diffuse, or specular light to varying degrees: point light sources (defined by a single point from which light is emitted in every direction, e.g. a light bulb), directional light sources (defined by a direction from which light is emitted, e.g. sunlight lighting a distant planet), and spot light sources (defined by a cone of light that starts from a position and points toward a direction, e.g. a stage spotlight). In this case, because we’re creating a hemispheric light source, which emits ambient light in a direction but has no single position, we only need a single three-dimensional vector to define its orientation.

Let’s modify this lighting code to experiment with the other light types. In each of the three examples below, we replace the hemispheric light with point, directional, and spot lights respectively. As we would expect, point lights (branch lighting-1 in the GitHub repository) only require one vector indicating position.

// Create a point light.

let light = new BABYLON.PointLight('light-1', new BABYLON.Vector3(0.5, 5, 0.5), scene);

Directional lights (branch lighting-2), meanwhile, act similarly to hemispheric lights in that they also only require a vector indicating direction. In this example, the directional light is originating from the right (x-value of –1).

// Create a directional light.

let light = new BABYLON.DirectionalLight('light-1', new BABYLON.Vector3(-1, 0, 0), scene);

Finally, spot lights (branch lighting-3) require arguments for position and direction (both three-dimensional vectors) as well as the angle of illumination (the size in radians of the spot light’s conical beam) and an exponent that defines how quickly the light decays over a distance.

Here, we have a position vector to place our spot light source high (y-value of 15) and to the rear (z-value of –15) to mimic a typical theater setup. The second directional vector indicates that the spotlight should point down (y-value of –1) and ahead (z-value of 1). The beam is limited to π/4 (45º) and decays at a rate of 3 (i.e. the light’s intensity decays by two-thirds with each unit in its reach).

// Create a spot light.

let light = new BABYLON.SpotLight('light-1', new BABYLON.Vector3(0, 15, -15), new BABYLON.Vector3(0, -1, 1), Math.PI / 4, 3, scene);

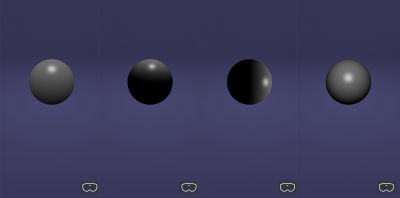

The screenshot set below illustrates the differences between ambient, point, directional, and spot light sources.

Light Parameters

There are certain parameters Babylon.js users can set for lights, such as intensity (light.intensity has a default value of 1) and color. Lights can also be turned off (light.setEnabled(false)) and on (light.setEnabled(true)).

// Set light intensity to a lower value (default is 1).

light.intensity = 0.5;

Let’s halve the light’s intensity by reducing the value to 0.25. Save the file and view it in the browser to see the result, which reflects the branch lighting-4 in the GitHub repository.

// Set light intensity to a lower value (default is 1).

light.intensity = 0.25;

Parameters are also available for adjusting the color of diffuse or specular light originating from a light source. We can add two additional lines to define diffuse and specular color (branch lighting-5). In this example, we make diffuse light blue and specular light red, which superimposes a shiny specular red dot on top of a more diffuse blue swath.

// Set diffuse light to blue and specular light to red.

light.diffuse = new BABYLON.Color3(0, 0, 1);

light.specular = new BABYLON.Color3(1, 0, 0);

The full range of lighting capabilities in Babylon.js, including lightmaps and projection textures, is well beyond this article, but the Babylon.js documentation on lights contains much more information.

Taking Shape: Set And Parametric Shapes

Now that we have lighting and a camera, we can add physical elements to our scene. Using Babylon.js’ built-in mesh builder, you can render both set and parametric shapes. Set shapes are those that usually have names in everyday usage and a well-known appearance, like boxes (also called cuboids), spheres, cylinders, cones, polygons, and planes. But set shapes also include shapes you might not use on a daily basis, such as toruses, torus knots, and polyhedra.

In the following example code, we create a sphere with a diameter of 2 units and with 32 horizontal segments used to render the shape.

// Add one of Babylon's built-in sphere shapes.

let sphere = BABYLON.MeshBuilder.CreateSphere('sphere-1', {

diameter: 2,

segments: 32

}, scene);

// Position the sphere up by half of its height.

sphere.position.y = 1;

If we adjust the parameters to include distinct diameters along the x-, y-, and z-axes, we can transform our sphere into an ellipsoid (branch shapes-1). In this example, the diameterY and diameterZ parameters override the default diameter of 2 on each axis.

// Add one of Babylon's built-in sphere shapes.

let sphere = BABYLON.MeshBuilder.CreateSphere('sphere-1', {

diameter: 2,

diameterY: 3,

diameterZ: 4,

segments: 32

}, scene);

Let’s create a truncated cone by applying the same differentiated diameters to a typical cylinder, which has optional upper and lower diameters in addition to a default diameter. When one of those diameters is equal to zero, the cylinder becomes a cone. When those diameters differ, we render a truncated cone instead (branch shapes-2). Here, the tessellation argument refers to how many radial sides should be rendered for the cone. All set shapes accept similar arguments that delineate how it should appear.

// Add one of Babylon's built-in cylinder shapes.

let cylinder = BABYLON.MeshBuilder.CreateCylinder('cylinder-1', {

diameterTop: 2,

diameterBottom: 5,

tessellation: 32

}, scene);

// Position the cylinder up by half of its height.

cylinder.position.y = 1;

Though well beyond the scope of this introduction to WebXR and Babylon.js, you can also create parametric shapes, which depend on input parameters to exist, like lines, ribbons, tubes, extruded shapes, lathes, and non-regular polygons, and polyhedra. which are three-dimensional shapes characterized by polygonal faces, straight edges, and sharp vertices. You can also create tiled planes and tiled boxes that carry a pattern or texture, like brick or knotted wood. Finally, you can create, combine, group, and sequence animations of materials and objects using both built-in animations and a keyframes-driven approach.

Putting It All Together: Rendering The Scene

Now that we’ve introduced a camera, a light, and a shape to our scene, it’s time to render it into an environment. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll stick with Babylon.js’ default environment, which gives us a ground as a floor and a “skybox,” a simulated sky.

// Create a default environment for the scene.

scene.createDefaultEnvironment();

Now, we can use Babylon.js’ default experience helper to check for browser or device compatibility with WebXR. If WebXR support is available, we return the constructed scene from the overarching createScene() function.

// Initialize XR experience with default experience helper.

const xrHelper = await scene.createDefaultXRExperienceAsync();

if (!xrHelper.baseExperience) {

// XR support is unavailable.

console.log('WebXR support is unavailable');

} else {

// XR support is available; proceed.

return scene;

}

};

We then create a default canvas based on the previous helper function we wrote, which instantiates a new engine and attaches it to the canvas element in our HTML.

// Create engine.

engine = createDefaultEngine();

if (!engine) {

throw 'Engine should not be null';

}

Finally, we invoke the createScene() function defined previously to use the engine to render the scene, in the process preparing Babylon.js for any future scenes we may need to render. In a WebXR-only implementation, a WebXR frame animation callback, represented by the XRSession method requestAnimationFrame(), is called each time the browser or device needs a new frame, such as the next one defined in an animation, to render the scene. In Babylon.js, the engine method runRenderLoop() serves this function.

// Create scene.

scene = createScene();

scene.then(function (returnedScene) {

sceneToRender = returnedScene;

});

// Run render loop to render future frames.

engine.runRenderLoop(function () {

if (sceneToRender) {

sceneToRender.render();

}

});

Because our current WebXR application encompasses the entire browser viewport, we want to ensure that whenever a user resizes the browser window, the scene’s dimensions update accordingly. To do so, we add an event listener for any browser resize that occurs.

// Handle browser resize.

window.addEventListener('resize', function () {

engine.resize();

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

If you run the code in the main branch or any of the other repository branches on a WebXR-compliant browser or device, you’ll see our completed scene. As a next step, try adding an animation to see the animation callback at work.

Next Steps: Supporting And Managing User Input

It’s one thing to establish a virtual or augmented world for viewers, but it’s another to implement user interactions that allow viewers to engage richly with your scene. WebXR includes two types of input: targeting (specifying a single point in space, such as through eye-tracking, tapping, or moving a cursor) and actions (involving both selection, like tapping a button, and squeezes, which are actions like pulling a trigger or squeezing a controller).

Because input can be mediated through a variety of input sources — touchscreens, motion-sensing controllers, grip pads, voice commands, and many other mechanisms — WebXR has no opinion about the types of input your application supports, beyond intelligent defaults. But because of the colossal surface area exposed by all input sources, especially in Babylon.js, it would take another full article in its own right to capture and respond to all manner of eye movements, joystick motions, gamepad moves, haptic glove squeezes, keyboard and mouse inputs, and other forms of input still over the horizon.

Debugging, Extending, And Bundling Babylon.js

Once you’ve completed the implementation of your WebXR application, it’s time to debug and test your code, extend it as desired for other rendering mechanisms and game physics engines, and to bundle it as a production-ready file. For a variety of use cases, Babylon.js has a rich ecosystem of debugging tools, rendering mechanisms, and even physics engines (and the ability to integrate your own) for realistic interactions between objects.

Debugging Babylon.js With The Inspector

Beyond the browser plugins available for WebXR emulation, Babylon.js also makes available an inspector for debugging (built in React). Unlike tools like Jest, because Babylon.js lacks an official command-line interface (CLI), debugging takes place directly in the code. To add the inspector to our Babylon.js application, we can add an additional external script to the embedded scripts in our <head>:

<!-- Embed Babylon inspector for debugging. -->

<script src="https://cdn.babylonjs.com/inspector/babylon.inspector.bundle.js"></script>

Then, just before we finish creating our scene, let’s indicate to Babylon.js that we want to render the scene in debug mode by adding the line scene.debugLayer.show() just before our return statement:

// Initialize XR experience with default experience helper.

const xrHelper = await scene.createDefaultXRExperienceAsync();

if (!xrHelper.baseExperience) {

// XR support is unavailable.

console.log('WebXR support is unavailable');

} else {

// XR support is available; proceed.

scene.debugLayer.show();

return scene;

}

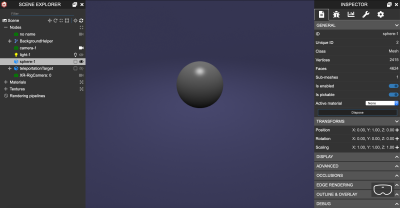

The next time you load your Babylon.js application in a browser, you’ll see a “Scene Explorer” to navigate rendered objects and an “Inspector” to view and adjust properties of all entities Babylon.js is aware of. The screenshot below shows how our application now looks with debug mode enabled, and branch debugging-1 reflects this state in the tutorial code.

The Babylon.js documentation offers both comprehensive information about loading and using the inspector and a series of videos about inspection and debugging.

Integrating And Bundling Babylon.js With Other JavaScript

Although over the course of this tutorial, we’ve used a script embedded directly into the HTML containing our canvas, you may wish to execute the script as an external file or to leverage an application framework like React or Ionic. Because Babylon.js makes all of its packages available on NPM, you can use NPM or Yarn to fetch Babylon.js as a dependency.

# Add ES6 version of Babylon.js as dependency using NPM.

$ npm install @babylonjs/core

# Add ES6 version of Babylon.js as dependency using Yarn.

$ yarn add @babylonjs/core

# Add non-ES6 version of Babylon.js as dependency using NPM.

$ npm install babylonjs

Documentation is available on the Babylon.js website for integrations of Babylon.js with React (including react-babylonjs, a React renderer for Babylon.js) and Ionic (a cross-platform framework). In the wild, Julien Noble has also written an experimental guide to leveraging Babylon.js in React Native’s web renderer.

For front-end performance reasons, you may also consider introducing a server-side rendering mechanism for the Babylon.js applications you build. Babylon.js offers a headless engine known as NullEngine, which replaces Babylon.js’ default Engine instance and can be used in Node.js or server-side environments where WebGL is absent. There are certain limitations, as you’ll need to implement a replacement for browser APIs like XMLHttpRequest in Node.js server frameworks like Express.

Meanwhile, on the client side, generating a lightweight client bundle that can be parsed quickly by a browser is a common best practice. While you can use Babylon.js’ CDN to download a minified version of the core Babylon.js library, you may also wish to combine Babylon.js and your Babylon.js implementation with other scripts like React by using a bundler such as Webpack. Leveraging Webpack allows you to use Babylon.js modularly with ES6 and TypeScript and to output client bundles representing the full scope of your JavaScript.

Immersing Yourself In WebXR

The road ahead for WebXR is bright if not fully formed. As people continue to seek more immersive and escapist experiences that enfold us completely in a virtual or augmented world, WebXR and Babylon.js adoption will only accelerate.

In these early days, as browser support solidifies and developer experiences mature, the promise of WebXR and rendering engines like Babylon.js can’t be understated. In this tutorial, we’ve only had a glimpse of the potential of immersive experiences on the web, but you can see all of our code on GitHub.

That said, it’s essential to remember that mixed reality and immersive experiences in WebXR can present problems for certain users. After all, virtual reality is, for all intents and purposes, a gambit to trick the viewer’s eyes and brain into perceiving objects that aren’t actually there. Many people experience virtual reality sickness, a dangerous illness with symptoms of disorientation, discomfort, and nausea. Physical objects that aren’t visible in virtual reality headsets can also pose hazards for users of immersive experiences. And perhaps most importantly, many immersive experiences are inaccessible for users with cognitive and physical disabilities such as blindness and vertigo-associated disorders.

Just as immersive experiences still remain out of reach for many users, whether due to lack of access to an immersive headset or WebXR-enabled browser or because of disabilities that stymie the user experience, mixed reality also remains a bit of a mystery for developers due to shifting sands in specifications and frameworks alike. Nonetheless, given immersive media waits just around the corner for digital marketing, we’ll see a new scene get the spotlight and take shape very soon — all puns very much intended.

Related Resources

WebXR

3D Graphics And WebGL

WebXR Device API

Babylon.js

- Babylon.js: Introduction to WebXR

- WebXR Experience Helpers

- WebXR Session Managers

- WebXR Camera

- WebXR Features Manager

- WebXR demos and examples

- WebXR input and controller support

- WebXR selected features

- WebXR augmented reality

Further Reading

- Exploring Animation And Interaction Techniques With WebGL (A Case Study)

- The Times You Need A Custom @property Instead Of A CSS Variable

- Sticky Headers And Full-Height Elements: A Tricky Combination

- How To Build Custom Data Visualizations Using Luzmo Flex